The Gupta Empire was an ancient Indian empire which existed from the early 4th century CE to early 6th century CE. At its zenith, from approximately 319 to 467 CE, it covered much of the Indian subcontinent. This period has been considered as the Golden Age of India by some historians, although this characterisation has been disputed by other historians. The ruling dynasty of the empire was founded by Gupta, and the most notable rulers of the dynasty were Chandragupta I, Samudragupta, Chandragupta II and Skandagupta. The 5th-century CE Sanskrit poet Kalidasa credits the Guptas with having conquered about twenty-one kingdoms, both in and outside India, including the kingdoms of Parasikas, the Hunas, the Kambojas, tribes located in the west and east Oxus valleys, the Kinnaras, Kiratas, and others.

Chandragupta II, also known by his title Vikramaditya, as well as Chandragupta Vikramaditya, was the third ruler of the Gupta Empire in India.

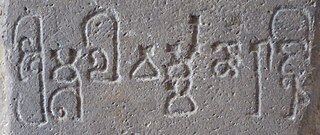

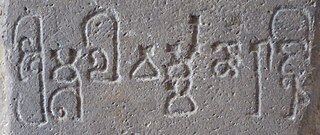

Samudragupta (Gupta script: Sa-mu-dra-gu-pta, was the second emperor of the Gupta Empire of ancient India, and is regarded among the greatest rulers of India. As a son of the Gupta emperor Chandragupta I and the Licchavi princess Kumaradevi, he greatly expanded his dynasty's political and military power. Samudragupta remained undefeated during his entire reign and is considered one of the greatest emperors in the history of the world. During his and his son, Chandragupta II's rule the Gupta Empire was undoubtedly the strongest and the most powerful empire in the world at that time.

Brahmi is a writing system of ancient India that appeared as a fully developed script in the third century BCE. Its descendants, the Brahmic scripts, continue to be used today across Southern and Southeastern Asia.

The Ashvamedha was a horse sacrifice ritual followed by the Śrauta tradition of Vedic religion. It was used by ancient Indian kings to prove their imperial sovereignty: a horse accompanied by the king's warriors would be released to wander for a year. In the territory traversed by the horse, any rival could dispute the king's authority by challenging the warriors accompanying it. After one year, if no enemy had managed to kill or capture the horse, the animal would be guided back to the king's capital. It would be then sacrificed, and the king would be declared as an undisputed sovereign.

Kanishka III, was a Kushan emperor who reigned from around the year 265 CE to 270 CE. He is believed to have succeeded Vasishka and was succeeded by Vasudeva II. He ruled in areas of Northwestern India.

Sodasa was an Indo-Scythian Northern Satrap and ruler of Mathura during the later part of the 1st century BCE or the early part of 1st century CE. He was the son of Rajuvula, the Great Satrap of the region from Taxila to Mathura. He is mentioned in the Mathura lion capital.

The Ikshvaku dynasty ruled in the eastern Krishna River valley of India, from their capital at Vijayapuri for over a century during 3rd and 4th centuries CE. The Ikshvakus are also known as the Andhra Ikshvakus or Ikshvakus of Vijayapuri to distinguish them from their legendary namesakes.

The Pallava script or Pallava Grantha is a Brahmic script named after the Pallava dynasty of Southern India and is attested to since the 4th century CE. In India, the Pallava script evolved into the Tamil and Grantha script. Pallava also spread to Southeast Asia and evolved into local scripts such as Balinese, Baybayin, Javanese, Kawi, Khmer, Lanna, Lao, Mon–Burmese, New Tai Lue alphabet, Sundanese, and Thai.

Vāsishka was a Kushan emperor, who seems to have had a short reign following Kanishka II.

Kutai is a historical region in what is now known as East Kalimantan, Indonesia on the island of Borneo and is also the name of the native ethnic group of the region, numbering around 300,000 who have their own language known as the Kutainese language which accompanies their own rich history. Today, the name is preserved in the names of three regencies in East Kalimantan province which are the Kutai Kartanegara Regency, the West Kutai Regency and the East Kutai Regency with the major river flowing in the heart of the region known as the Mahakam River. Kutai is known to be the place of the first and oldest Hindu kingdom to exist in East Indies Archipelago, the Kutai Martadipura Kingdom which was later succeeded by the Muslim Kutai Kartanegara Sultanate.

Sri Mulavarman Nala Deva, was the king of the Kutai Martadipura Kingdom located in eastern Borneo around the year 400 CE. What little is known of him comes from the seven Yupa inscriptions found at a sanctuary in Kutai, East Kalimantan. He is known to have been generous to brahmins through the giving of gifts including thousands of cattle and large amounts of gold.

A good number of inscriptions written in Sanskrit language have been found in Malaysia and Indonesia. "Early inscriptions written in Indian languages and scripts abound in Southeast Asia. [...] The fact that southern Indian languages didn't travel eastwards along with the script further suggests that the main carriers of ideas from the southeast coast of India to the east - and the main users in Southeast Asia of religious texts written in Sanskrit and Pali - were Southeast Asians themselves. The spread of these north Indian sacred languages thus provides no specific evidence for any movements of South Asian individuals or groups to Southeast Asia.

Kudungga was the founder of the Kutai Martadipura kingdom who ruled around the year 350 AD or 4th century AD. Kudungga first ruled the kingdom of Kutai Martadipura as a community leader or chieftain. Kutai Martadipura during Kudungga rule do not have a regular and systematical system of governance. In contrary, the latest claim is said that Maharaja Kudungga is possibly a king from ancient kingdom Bakulapura in Tebalrung , and Asvavarman which his son-in-law rather his son, then become the first king of Kutai Martadipura.

The Northern Satraps, or sometimes Satraps of Mathura, or Northern Sakas, are a dynasty of Indo-Scythian ("Saka") rulers who held sway over the area of Punjab and Mathura after the decline of the Indo-Greeks, from the end of the 1st century BCE to the 2nd century CE. They are called "Northern Satraps" in modern historiography to differentiate them from the "Western Satraps", who ruled in Sindh, Gujarat and Malwa at roughly the same time and until the 4th century CE. They are thought to have replaced the last of the Indo-Greek kings in the Punjab region, as well as the Mitra dynasty and the Datta dynasty of local Indian rulers in Mathura.

The Art of Mathura refers to a particular school of Indian art, almost entirely surviving in the form of sculpture, starting in the 2nd century BCE, which centered on the city of Mathura, in central northern India, during a period in which Buddhism, Jainism together with Hinduism flourished in India. Mathura "was the first artistic center to produce devotional icons for all the three faiths", and the pre-eminent center of religious artistic expression in India at least until the Gupta period, and was influential throughout the sub-continent.

Ayodhya Inscription of Dhana is a stone inscription related to a Hindu Deva king named Dhana or Dhana–deva of the 1st-century BCE or 1st century CE. He ruled from the city of Ayodhya, Kosala, in India. His name is found in ancient coins and the inscription. According to P. L. Gupta, he was among the fifteen kings who ruled from Ayodhya between 130 BCE and 158 CE, and whose coins have been found: Muladeva, Vayudeva, Vishakadeva, Dhanadeva, Ajavarman, Sanghamirta, Vijayamitra, Satyamitra, Devamitra and Aryamitra. D.C. Sircar dates the inscription to 1st-century CE based on the epigraphical evidence. The paleography of the inscription is identical to that of the Northern Satraps in Mathura, which gives a 1st century CE date. The damaged inscription is notable for its mention of general Pushyamitra and his descendant Dhana–, his use of Vedic Ashvamedha horse to assert the range of his empire, and the building of a temple shrine.

The Lakulisa Mathura Pillar Inscription is a 4th-century CE Sanskrit inscription in early Gupta script related to the Shaivism tradition of Hinduism. Discovered near a Mathura well in north India, the damaged inscription is one of the earliest evidences of murti (statue) consecration in a temple made to celebrate gurus. It is, according to the Indologist Michael Willis, crucial to understanding the "history of Pashupata Shaivism" and a floruit for the antiquity of its practices. The Lakulisha Mathura inscription is one of the earliest epigraphical evidence of a developed Shaiva initiation tradition.

Gupta art is the art of the Gupta Empire, which ruled most of northern India, with its peak between about 300 and 480 CE, surviving in much reduced form until c. 550. The Gupta period is generally regarded as a classic peak and golden age of North Indian art for all the major religious groups. Gupta art is characterized by its "Classical decorum", in contrast to the subsequent Indian medieval art, which "subordinated the figure to the larger religious purpose".

Indo-Scythian art developed under the various dynasties of Indo-Scythian rulers in northwestern India, from the 1st century BCE to the early 5th century CE, encompassing the productions of the early Indo-Scythians, the Northern Satraps and the Western Satraps. It follows the development of Indo-Greek art in northwestern India. The Scythians in India were ultimately replaced by the Kushan Empire and the Gupta Empire, whose art form appear in Kushan art and Gupta art.