Politics of the Democratic Republic of Congo take place in the framework of a republic in transition from a civil war to a semi-presidential republic.

Zaire, officially the Republic of Zaire, was the name of the Democratic Republic of the Congo from 1971 to 1997. Located in Central Africa, it was, by area, the third-largest country in Africa after Sudan and Algeria, and the 11th-largest country in the world from 1965 to 1997. With a population of over 23 million, Zaire was the most populous Francophone country in Africa. Zaire played a central role during the Cold War.

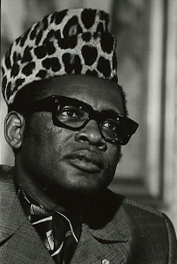

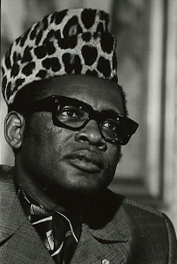

Mobutu Sese Seko Kuku Ngbendu wa za Banga, often shortened to Mobutu Sese Seko or Mobutu and also known by his initials MSS, was a Congolese politician and military officer who was the 1st and only President of Zaire from 1971 to 1997. Previously, Mobutu served as the 2nd President of the Democratic Republic of the Congo from 1965 to 1971. He also served as the 5th Chairman of the Organisation of African Unity from 1967 to 1968. During the Congo Crisis, Mobutu, serving as Chief of Staff of the Army and supported by Belgium and the United States, deposed the democratically elected government of left-wing nationalist Patrice Lumumba in 1960. Mobutu installed a government that arranged for Lumumba's execution in 1961, and continued to lead the country's armed forces until he took power directly in a second coup in 1965.

Joseph Kasa-Vubu, alternatively Joseph Kasavubu, was a Congolese politician who served as the first President of the Democratic Republic of the Congo from 1960 until 1965.

Moïse Kapenda Tshombe was a Congolese businessman and politician. He served as the president of the secessionist State of Katanga from 1960 to 1963 and as prime minister of the Democratic Republic of the Congo from 1964 to 1965.

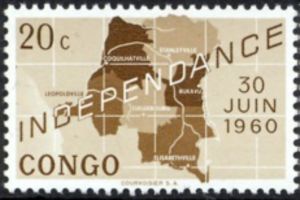

The Congo Crisis was a period of political upheaval and conflict between 1960 and 1965 in the Republic of the Congo. The crisis began almost immediately after the Congo became independent from Belgium and ended, unofficially, with the entire country under the rule of Joseph-Désiré Mobutu. Constituting a series of civil wars, the Congo Crisis was also a proxy conflict in the Cold War, in which the Soviet Union and the United States supported opposing factions. Around 100,000 people are believed to have been killed during the crisis.

Étienne Tshisekedi wa Mulumba was a Congolese politician and the leader of the Union for Democracy and Social Progress (UDPS), formerly the main opposition political party in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC). A long-time opposition leader, he served as Prime Minister of the country on three brief occasions: in 1991, 1992–1993, and 1997. He was also the father of the current President, Felix Tshisekedi.

Jean Nguza Karl-i-Bond was a prominent Zairian politician.

The Prime Minister of the Democratic Republic of the Congo is the head of government of the Democratic Republic of the Congo. The Constitution of the Third Republic grants the Prime Minister a significant amount of power.

Albert Kalonji was a Congolese politician and businessman from the Luba ya Kasai nobility. He was elected emperor (Mulopwe) of the Baluba ya Kasai(Bambo) and later became king of the Federated State of South Kasai.

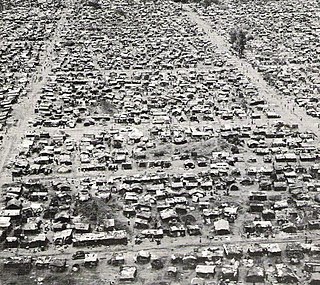

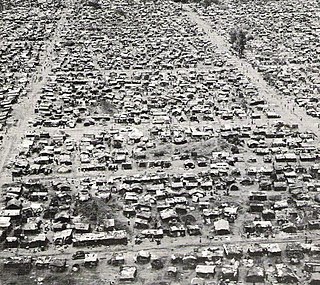

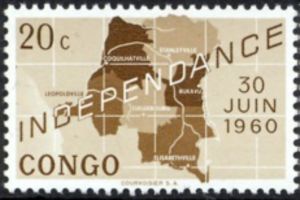

The Republic of the Congo was a sovereign state in Central Africa, created with the independence of the Belgian Congo in 1960. From 1960 to 1966, the country was also known as Congo-Léopoldville to distinguish it from its northwestern neighbor, which is also called the Republic of the Congo, alternatively known as "Congo-Brazzaville". In 1964, the state's official name was changed to the Democratic Republic of the Congo, but the two countries continued to be distinguished by their capitals; with the renaming of Léopoldville as Kinshasa in 1966, it became also known as Congo-Kinshasa. After Joseph Désiré Mobutu, commander-in-chief of the national army, seized control of the government in 1965, the Democratic Republic of the Congo became the Republic of Zaire in 1971. It would again become the Democratic Republic of the Congo in 1997. The period between 1960 and 1964 is referred to as the First Congolese Republic.

Bernardin Mungul Diaka was a Congolese/Zairean diplomat and politician.

Presidential elections were held in the Democratic Republic of the Congo on 1 November 1970. The only candidate was Joseph Mobutu, who had taken power in a military coup five years earlier. The elections took the format of a "yes" or "no" vote for Mobutu's candidacy. According to official figures, Mobutu was confirmed in office with near-unanimous support, with only 157 "no" votes out of over 10.1 million total votes cast. Mobutu also received around 30,000 more "yes" votes than the number of registered voters, even though voting was not compulsory.

The Constitution of Zaire, was promulgated on 15 August 1974, revised on 15 February 1978, and amended on 5 July 1990. It provided a renewed legal basis for the regime of Mobutu Sese Seko who had emerged as the country's dictator after the Congo Crisis in 1965.

Cléophas Kamitatu Massamba was a Congolese politician and leader of the Parti Solidaire Africain.

Marcel Antoine Lihau or Ebua Libana la Molengo Lihau was a Congolese jurist, law professor and politician who served as the inaugural First President of the Supreme Court of Justice of the Congo from 1968 until 1975, and was involved in the creation of two constitutions for the Democratic Republic of the Congo.

Rémy Mwamba (1921–1967) was a Congolese politician who twice served as Minister of Justice of the Democratic Republic of the Congo. He was also a leading figure of the Association Générale des Baluba du Katanga (BALUBAKAT).

In the Democratic Republic of the Congo, it is common for individuals to possess three separate names: a first name (prénom) and surname (nom) as well as a post-surname (postnom). Each form may comprise one or more elements. For example:

Albert Nyembo Mwana-Ngongo is a Congolese and Katangese politician who was a Secretary of State and Minister for Congo and secessionist Katanga.

Dominique Diur (1929—1980) was a Congolese and Katangese politician who was one of the founders of the CONAKAT party.