The Eucharist, also known as Holy Communion, Blessed Sacrament and the Lord's Supper, is a Christian rite that is considered a sacrament in most churches, and as an ordinance in others. Christians believe that the rite was instituted by Jesus at the Last Supper, the night before his crucifixion, giving his disciples bread and wine. Passages in the New Testament state that he commanded them to "do this in memory of me" while referring to the bread as "my body" and the cup of wine as "the blood of my covenant, which is poured out for many". According to the Synoptic Gospels this was at a Passover meal.

Transubstantiation is, according to the teaching of the Catholic Church, "the change of the whole substance of bread into the substance of the Body of Christ and of the whole substance of wine into the substance of the Blood of Christ". This change is brought about in the eucharistic prayer through the efficacy of the word of Christ and by the action of the Holy Spirit. However, "the outward characteristics of bread and wine, that is the 'eucharistic species', remain unaltered". In this teaching, the notions of "substance" and "transubstantiation" are not linked with any particular theory of metaphysics.

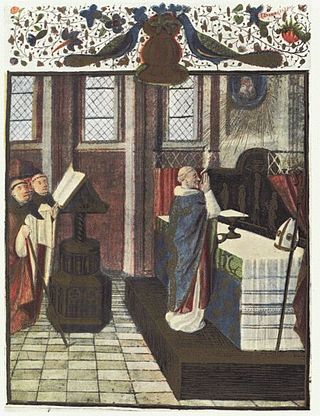

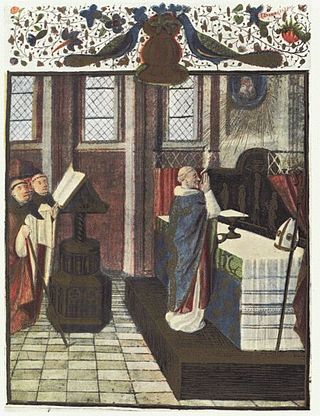

Mass is the main Eucharistic liturgical service in many forms of Western Christianity. The term Mass is commonly used in the Catholic Church, Western Rite Orthodoxy, Old Catholicism, and Independent Catholicism. The term is also used in some Lutheran churches, as well as in some Anglican churches, and on rare occasion by other Protestant churches.

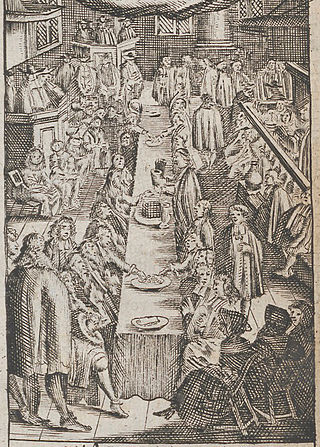

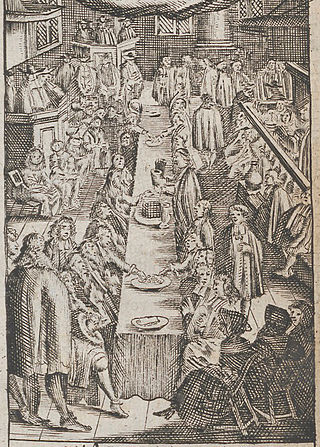

Closed communion is the practice of restricting the serving of the elements of Holy Communion to those who are members in good standing of a particular church, denomination, sect, or congregation. Though the meaning of the term varies slightly in different Christian theological traditions, it generally means that a church or denomination limits participation either to members of their own church, members of their own denomination, or members of some specific class. This restriction is based on various parameters, one of which is baptism. See also intercommunion.

The real presence of Christ in the Eucharist is the Christian doctrine that Jesus Christ is present in the Eucharist, not merely symbolically or metaphorically, but in a true, real and substantial way.

In Christian theology, the term Body of Christ has two main but separate meanings: it may refer to Jesus Christ's words over the bread at the celebration of the Jewish feast of Passover that "This is my body" in Luke 22:19–20, or it may refer to all individuals who are "in Christ" 1 Corinthians 12:12–14.

The Words of Institution are words echoing those of Jesus himself at his Last Supper that, when consecrating bread and wine, Christian Eucharistic liturgies include in a narrative of that event. Eucharistic scholars sometimes refer to them simply as the verba.

Eucharistic discipline is the term applied to the regulations and practices associated with an individual preparing for the reception of the Eucharist. Different Christian traditions require varying degrees of preparation, which may include a period of fasting, prayer, repentance, and confession.

The Ubiquitarians, also called Ubiquists, were a Protestant sect that held that the body of Christ was everywhere, including the Eucharist. The sect was started at the Lutheran synod of Stuttgart, 19 December 1559, by Johannes Brenz (1499–1570), a Swabian. Its profession, made under the name of Duke Christopher of Württemberg and entitled the "Württemberg Confession," was sent to the Council of Trent in 1552, but had not been formally accepted as the Ubiquitarian creed until the synod at Stuttgart.

Eucharistic theology is a branch of Christian theology which treats doctrines concerning the Holy Eucharist, also commonly known as the Lord's Supper and Holy Communion. It exists exclusively in Christianity, as others generally do not contain a Eucharistic ceremony.

The Encratites ("self-controlled") were an ascetic 2nd-century sect of Christians who forbade marriage and counselled abstinence from meat. Eusebius says that Tatian was the author of this heresy. It has been supposed that it was these Gnostic Encratites who were chastised in the epistle of 1 Timothy (4:1-4).

During the Liturgy of the Eucharist, the second part of the Mass, the elements of bread and wine are considered to have been changed into the veritable Body and Blood of Jesus Christ. The manner in which this occurs is referred to by the term transubstantiation, a theory of St. Thomas Aquinas, in the Roman Catholic Church. Members of the Orthodox, Anglican, and Lutheran communions also believe that Jesus Christ is really and truly present in the bread and wine, but they believe that the way in which this occurs must forever remain a sacred mystery. In many Christian churches, some portion of the consecrated elements is set aside and reserved after the reception of Communion and referred to as the reserved sacrament. The reserved sacrament is usually stored in a tabernacle, a locked cabinet made of precious materials and usually located on, above, or near the high altar. In Western Christianity usually only the Host, from Latin: hostia, meaning "victim", is reserved, except where wine might be kept for the sick who cannot consume a host.

Anglican eucharistic theology is diverse in practice, reflecting the comprehensiveness of Anglicanism. Its sources include prayer book rubrics, writings on sacramental theology by Anglican divines, and the regulations and orientations of ecclesiastical provinces. The principal source material is the Book of Common Prayer, specifically its eucharistic prayers and Article XXVIII of the Thirty-Nine Articles. Article XXVIII comprises the foundational Anglican doctrinal statement about the Eucharist, although its interpretation varies among churches of the Anglican Communion and in different traditions of churchmanship such as Anglo-Catholicism and Evangelical Anglicanism.

Eucharist is the name that Catholic Christians give to the sacrament by which, according to their belief, the body and blood of Christ are present in the bread and wine consecrated during the Catholic eucharistic liturgy, generally known as the Mass. The definition of the Eucharist in the 1983 Code of Canon Law as the sacrament where Christ himself "is contained, offered, and received" points to the three aspects of the Eucharist according to Catholic theology: the real presence of Christ in the Eucharist, Holy Communion, and the holy sacrifice of the Mass.

The Mass is the central liturgical service of the Eucharist in the Catholic Church, in which bread and wine are consecrated and become the body and blood of Christ. As defined by the Church at the Council of Trent, in the Mass "the same Christ who offered himself once in a bloody manner on the altar of the cross, is present and offered in an unbloody manner". The Church describes the Mass as the "source and summit of the Christian life", and teaches that the Mass is a sacrifice, in which the sacramental bread and wine, through consecration by an ordained priest, become the sacrificial body, blood, soul, and divinity of Christ as the sacrifice on Calvary made truly present once again on the altar. The Catholic Church permits only baptised members in the state of grace to receive Christ in the Eucharist.

Christian views on alcohol are varied. Throughout the first 1,800 years of Church history, Christians generally consumed alcoholic beverages as a common part of everyday life and used "the fruit of the vine" in their central rite—the Eucharist or Lord's Supper. They held that both the Bible and Christian tradition taught that alcohol is a gift from God that makes life more joyous, but that over-indulgence leading to drunkenness is sinful. However, the alcoholic content of ancient alcoholic beverages was significantly lower than that of modern alcoholic beverages. The low alcoholic content was due to the limitations of fermentation and the nonexistence of distillation methods in the ancient world. Rabbinic teachers wrote acceptance criteria on consumability of ancient alcoholic beverages after significant dilution with water, and prohibited undiluted wine.

Communion under both kinds in Christianity is the reception under both "species" of the Eucharist. Denominations of Christianity that hold to a doctrine of Communion under both kinds may believe that a Eucharist which does not include both bread and wine as elements of the religious ceremony is not valid, while others may consider the presence of both bread and wine as preferable, but not necessary, for the ceremony. In some traditions, grape juice may take the place of wine with alcohol content as the second element.

In Lutheranism, the Eucharist refers to the liturgical commemoration of the Last Supper. Lutherans believe in the real presence of Christ in the Eucharist, affirming the doctrine of sacramental union, "in which the body and blood of Christ are truly and substantially present, offered, and received with the bread and wine."

In Reformed theology, the Lord's Supper or Eucharist is a sacrament that spiritually nourishes Christians and strengthens their union with Christ. The outward or physical action of the sacrament is eating bread and drinking wine. Reformed confessions, which are official statements of the beliefs of Reformed churches, teach that Christ's body and blood are really present in the sacrament and that believers receive, in the words of the Belgic Confession, "the proper and natural body and the proper blood of Christ." The primary difference between the Reformed doctrine and that of Catholic and Lutheran Christians is that for the Reformed, this presence is believed to be communicated in a spiritual manner by faith rather than by oral consumption. The Reformed doctrine of real presence is called "pneumatic presence".