Apocrypha are biblical or related writings not forming part of the accepted canon of Scripture. While some might be of doubtful authorship or authenticity, in Christianity, the word apocryphal (ἀπόκρυφος) was first applied to writings which were to be read privately rather than in the public context of church services. Apocrypha were edifying Christian works that were not considered canonical scripture. It was not until well after the Protestant Reformation that the word apocrypha was used by some ecclesiastics to mean "false," "spurious," "bad," or "heretical."

The deuterocanonical books are books and passages considered by the Catholic Church, the Eastern Orthodox Church, the Oriental Orthodox Churches or the Assyrian Church of the East to be canonical books of the Old Testament, but which Jews and Protestants regard as apocrypha. They date from 300 BC to 100 AD, before the separation of the Christian church from Judaism. While the New Testament never directly quotes from or names these books, the apostles quoted the Septuagint, which includes them. Some say there is a correspondence of thought, and others see texts from these books being paraphrased, referred, or alluded to many times in the New Testament, depending in large measure on what is counted as a reference.

Pope Damasus I, known as Damasus of Rome, was the bishop of Rome from October 366 to his death. He presided over the Council of Rome of 382 that determined the canon or official list of sacred scripture. He spoke out against major heresies, thus solidifying the faith of the Catholic Church, and encouraged production of the Vulgate Bible with his support for Jerome. He helped reconcile the relations between the Church of Rome and the Church of Antioch, and encouraged the veneration of martyrs.

Pope Gelasius I was the bishop of Rome from 1 March 492 to his death on 19 November 496. Gelasius was a prolific author whose style placed him on the cusp between Late Antiquity and the Early Middle Ages. Some scholars have argued that his predecessor Felix III may have employed him to draft papal documents, although this is not certain.

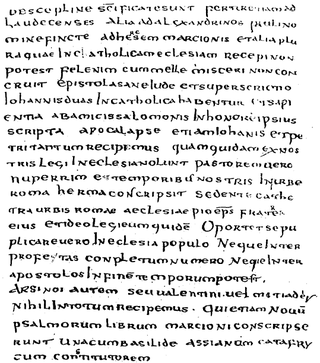

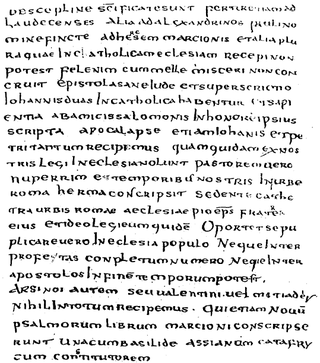

The Muratorian fragment, also known as the Muratorian Canon, is a copy of perhaps the oldest known list of most of the books of the New Testament. The fragment, consisting of 85 lines, is a Latin manuscript bound in a roughly 8th-century codex from the library of Columbanus's monastery at Bobbio Abbey; it contains features suggesting it is a translation from a Greek original written about 170. Other scholars suggest it might have been originally written as late as the 4th century, although this is not the consensus opinion. Both the degraded condition of the manuscript and the poor Latin in which it was written have made it difficult to translate. The beginning of the fragment is missing, and it ends abruptly. The fragment consists of all that remains of a section of a list of all the works that were accepted as canonical by the churches known to its original compiler.

Decretals are letters of a pope that formulate decisions in ecclesiastical law of the Catholic Church.

In the Western Church of the Early and High Middle Ages, a sacramentary was a book used for liturgical services and the mass by a bishop or priest. Sacramentaries include only the words spoken or sung by him, unlike the missals of later centuries that include all the texts of the mass whether read by the bishop, priest, or others. Also, sacramentaries, unlike missals, include texts for services other than the mass such as ordinations, the consecration of a church or altar, exorcisms, and blessings, all of which were later included in Pontificals and Rituals instead.

Lucian of Antioch, known as Lucian the Martyr, was a Christian presbyter, theologian and martyr. He was noted for both his scholarship and ascetic piety.

The Decretum Gratiani, also known as the Concordia discordantium canonum or Concordantia discordantium canonum or simply as the Decretum, is a collection of canon law compiled and written in the 12th century as a legal textbook by the jurist known as Gratian. It forms the first part of the collection of six legal texts, which together became known as the Corpus Juris Canonici. It was used as the main source of law by canonists of the Roman Catholic Church until the Decretals, promulgated by Pope Gregory IX in 1234, obtained legal force, after which it was the cornerstone of the Corpus Juris Canonici, in force until 1917.

The Apostolic Canons, also called Apostolic canons, Ecclesiastical Canons of the Same Holy Apostles, or Canons of the Holy Apostles, is a 4th-century Syrian Christian text. It is an Ancient Church Order, a collection of ancient ecclesiastical canons concerning the government and discipline of the Early Christian Church, allegedly written by the Apostles. This text is an appendix to the eighth book of the Apostolic Constitutions. Like the other Ancient Church Orders, the Apostolic Canons uses a pseudepigraphic form.

The Apocalypse of Thomas is a work from the New Testament apocrypha, apparently composed originally in Greek. It concerns the end of the world, and appears to be influenced by the Apocalypse of John, although it is written in a less mystical and cosmic manner. The Apocalypse of Thomas is the inspiration for the popular medieval millennial list Fifteen Signs before Doomsday.

The Council of Rome was a synod which took place in Rome in AD 382, under the leadership of Pope Damasus I, the then-Bishop of Rome. The only surviving conciliar pronouncement may be the Decretum Gelasianum that contains a canon of Scripture, which was issued by the Council of Rome under Pope Damasus in 382, and which is identical with the list given at the Council of Trent.

Saint Victorinus of Pettau was an Early Christian ecclesiastical writer who flourished about 270, and who was martyred during the persecutions of Emperor Diocletian. A Bishop of Poetovio in Pannonia, Victorinus is also known as Victorinus Petavionensis or Poetovionensis. Victorinus composed commentaries on various texts within the Christians' Holy Scriptures.

The Corpus Juris Canonici is a collection of significant sources of the Canon law of the Catholic Church that was applicable to the Latin Church. It was replaced by the 1917 Code of Canon Law which went into effect in 1918. The 1917 Code was later replaced by the 1983 Code of Canon Law, the codification of canon law currently in effect for the Latin Church.

Collections of ancient canons contain collected bodies of canon law that originated in various documents, such as papal and synodal decisions, and that can be designated by the generic term of canons.

The Old Testament is the first section of the two-part Christian biblical canon; the second section is the New Testament. The Old Testament includes the books of the Hebrew Bible (Tanakh) or protocanon, and in various Christian denominations also includes deuterocanonical books. Orthodox Christians, Catholics and Protestants use different canons, which differ with respect to the texts that are included in the Old Testament.

A biblical canon is a set of texts which a particular Jewish or Christian religious community regards as part of the Bible.

The canon of the New Testament is the set of books many modern Christians regard as divinely inspired and constituting the New Testament of the Christian Bible. For historical Christians, canonicalization was based on whether the material was written by the apostles or their close associates, rather than claims of divine inspiration. However, some biblical scholars with diverse disciplines now reject the claim that any texts of the Bible were written by the earliest apostles.

The Collectio canonum Quesnelliana is a vast collection of canonical and doctrinal documents prepared (probably) in Rome sometime between 494 and (probably) 610. It was first identified by Pierre Pithou and first edited by Pasquier Quesnel in 1675, whence it takes its modern name. The standard edition used today is that prepared by Girolamo and Pietro Ballerini in 1757.

Passion Gospels are early Christian texts that either mostly or exclusively relate to the last events of Jesus' life: the Passion of Jesus. They are generally classed as New Testament apocrypha. The last chapters of the four canonical gospels include Passion narratives, but later Christians hungered for more details. Just as infancy gospels expanded the stories of young Jesus, Passion Gospels expanded the story of Jesus's arrest, trial, execution, resurrection, and the aftermath. These documents usually claimed to be written by a participant mentioned in the gospels, with Nicodemus, Pontius Pilate, and Joseph of Arimathea as popular choices for author. These documents are considered more legendary than historical, however, and were not included in the eventual Canon of the New Testament.