Kenyanthropus is a genus of extinct hominin identified from the Lomekwi site by Lake Turkana, Kenya, dated to 3.3 to 3.2 million years ago during the Middle Pliocene. It contains one species, K. platyops, but may also include the 2 million year old Homo rudolfensis, or K. rudolfensis. Before its naming in 2001, Australopithecus afarensis was widely regarded as the only australopithecine to exist during the Middle Pliocene, but Kenyanthropus evinces a greater diversity than once acknowledged. Kenyanthropus is most recognisable by an unusually flat face and small teeth for such an early hominin, with values on the extremes or beyond the range of variation for australopithecines in regard to these features. Multiple australopithecine species may have coexisted by foraging for different food items, which may be reason why these apes anatomically differ in features related to chewing.

Orrorin is an extinct genus of primate within Homininae from the Miocene Lukeino Formation and Pliocene Mabaget Formation, both of Kenya.

Homo rudolfensis is an extinct species of archaic human from the Early Pleistocene of East Africa about 2 million years ago (mya). Because H. rudolfensis coexisted with several other hominins, it is debated what specimens can be confidently assigned to this species beyond the lectotype skull KNM-ER 1470 and other partial skull aspects. No bodily remains are definitively assigned to H. rudolfensis. Consequently, both its generic classification and validity are debated without any wide consensus, with some recommending the species to actually belong to the genus Australopithecus as A. rudolfensis or Kenyanthropus as K. rudolfensis, or that it is synonymous with the contemporaneous and anatomically similar H. habilis.

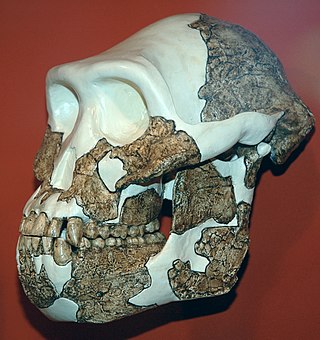

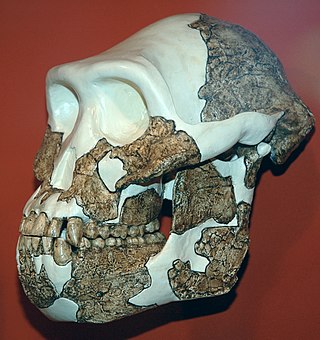

Pierolapithecus catalaunicus is an extinct species of primate which lived around 12.5-13 million years ago during the Miocene in what is now Hostalets de Pierola, Catalonia, Spain. Some researchers believe that it is a candidate for common ancestor to the great ape clade, or is at least closer than any previous fossil discovery. Others suggest it being a pongine, or a dryopith. On 16 October 2023, scientists reported the facial reconstruction of the great ape.

Aegyptopithecus is an early fossil catarrhine that predates the divergence between hominoids (apes) and cercopithecids. It is known from a single species, Aegyptopithecus zeuxis, which lived around 38-29.5 million years ago in the early part of the Oligocene epoch. It likely resembled modern-day New World monkeys, and was about the same size as a modern howler monkey, which is about 56 to 92 cm long. Aegyptopithecus fossils have been found in the Jebel Qatrani Formation of modern-day Egypt. Aegyptopithecus is believed to be a stem-catarrhine, a crucial link between Eocene and Miocene fossils.

Proconsul is an extinct genus of primates that existed from 21 to 17 million years ago during the Miocene epoch. Fossil remains are present in Eastern Africa, including Kenya and Uganda. Four species have been classified to date: P. africanus, P. gitongai, P. major and P. meswae. The four species differ mainly in body size. Environmental reconstructions for the Early Miocene Proconsul sites are still tentative and range from forested environments to more open, arid grasslands.

Australopithecus anamensis is a hominin species that lived approximately between 4.3 and 3.8 million years ago and is the oldest known Australopithecus species, living during the Plio-Pleistocene era.

Victoriapithecus macinnesi was a primate from the middle Miocene that lived approximately 15 to 17 million years ago in Northern and Eastern Africa. Through extensive field work on Maboko Island in Lake Victoria, Kenya, over 3,500 specimens have been found, making V. macinnesi one of the best-known fossil primates. It was previously thought that perhaps multiple species of Victoriapithecus were found, however the majority of fossils found indicate there is only one species, V. macinnesi. Victoriapithecus shows similarities to the extant subfamilies Colobinae and Cercopithecinae. However, Victoriapithecus predates the last common ancestor of these two groups and instead is thought to be a sister taxon.

Ekembo nyanzae, originally classed as a species of Proconsul, is a species of fossil primate first discovered by Louis Leakey on Rusinga Island in 1942, which he published in Nature in 1943. It is also known by the name Dryopithecus africanus. A joint publication of Wilfrid Le Gros Clark and Louis Leakey in 1951, "The Miocene Hominoidea of East Africa", first defines Proconsul nyanzae. In 1965 Simons and Pilbeam replaced Proconsul with Dryopithecus, using the same species names.

Nakalipithecus nakayamai, sometimes referred to as the Nakali ape, is an extinct species of great ape from Nakali, Kenya, from about 9.9–9.8 million years ago during the Late Miocene. It is known from a right jawbone with 3 molars and from 11 isolated teeth. The jawbone specimen is presumed female as the teeth are similar in size to those of female gorillas and orangutans. Compared to other great apes, the canines are short, the enamel is thin, and the molars are flatter. Nakalipithecus seems to have inhabited a sclerophyllous woodland environment.

Lufengpithecus is an extinct genus of ape, known from the Late Miocene of East Asia. It is known from thousands of dental remains and a few skulls and probably weighed about 50 kg (110 lb). It contains three species: L. lufengensis, L. hudienensis and L. keiyuanensis. Lufengpithecus lufengensis is from the Late Miocene found in China, named after the Lufeng site and dated around 6.2 Ma. Lufengpithecus is either thought to be the sister group to Ponginae, or the sister to the clade containing Ponginae and Homininae.

Samburupithecus is an extinct primate that lived in Kenya during the middle to late Miocene. The one species in this genus, Samburupithecus kiptalami, is known only from a maxilla fragment dated to 9.5 million years ago discovered in 1982 and formally described by Ishida & Pickford 1997. The type specimen KNM-SH 8531 was discovered by the Joint Japan-Kenya Expedition at the SH22 fossil site in the Samburu District, a locality where several other researchers found no ape fossils.

Kamoyapithecus was a primate that lived in Africa during the late Oligocene period, about 24.2-27.5 million years ago. First found in 1948 as part of a University of California, Berkeley expedition, it was at first thought to be under a form of Proconsul by C.T. Madden in 1980, but after a re-examination by Meave Leakey and associates later, the fossils were moved under a new genus Kamoyapithecus, named after the renowned fossil finder Kamoya Kimeu. The genus is represented by only one species, K. hamiltoni.

Morotopithecus is a genus of fossil ape discovered in Miocene-age deposits of Moroto, Uganda.

Equatorius is an extinct genus of kenyapithecine primate found in central Kenya at the Tugen Hills. Thirty-eight large teeth belonging to this middle Miocene hominid in addition to a mandibular and partially complete skeleton dated 15.58 Ma and 15.36 Ma. were later found.

Plesiopithecus is an extinct genus of early strepsirrhine primate from the late Eocene.

Ouranopithecus macedoniensis is a prehistoric species of Ouranopithecus from the Late Miocene of Greece. See more detail at Ouranopithecus.

Ekembo is an early ape (hominoid) genus found in 17- to 20-million-year-old sediments from the Miocene epoch. Specimens have been found at sites around the ancient Kisingiri volcano in Kenya on Rusinga Island and Mfangano Island in Lake Victoria. The name Ekembo is Suba for "ape" or "monkey".

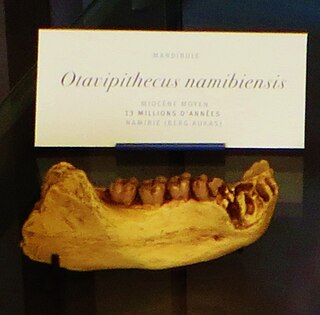

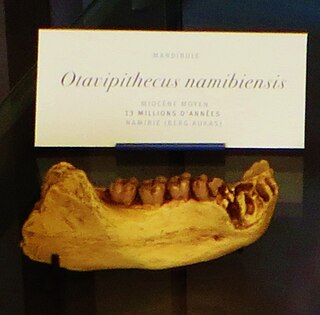

Otavipithecus namibiensis is an extinct species of ape from the Miocene of Namibia. The fossils were discovered at the Berg Aukas mines in the foothills of the Otavi mountains, hence the generic name. The species was described in 1992 by Glenn Conroy and colleagues, and was at the time the only non-hominin fossil ape known from Southern Africa. The scientists noted that the surrounding area of the discovered specimen included fauna dated at "about 13 ± 1 Myr". The fossils consist of part of the lower jawbone with molars, a partial frontal bone, a heavily damaged ulna, one vertebra and a partial finger bone.

Katifelis is an extinct genus of felids that lived in what is now Kenya during the Early Miocene and is notable for its dental features, which are intermediate between basal and modern cats. It contains a single species, Katifelis nightingalei.