Homininae, is a subfamily of the family Hominidae (hominids). This subfamily includes two tribes, Hominini and Gorillini, both having extant species as well as extinct species.

Orrorin is an extinct genus of primate within Homininae from the Miocene Lukeino Formation and Pliocene Mabaget Formation, both of Kenya.

Oreopithecus is an extinct genus of hominoid primate from the Miocene epoch whose fossils have been found in today's Tuscany and Sardinia in Italy. It existed nine to seven million years ago in the Tusco-Sardinian area when this region was an isolated island in a chain of islands stretching from central Europe to northern Africa in what was becoming the Mediterranean Sea.

Pierolapithecus catalaunicus is an extinct species of primate which lived around 12.5-13 million years ago during the Miocene in what is now Hostalets de Pierola, Catalonia, Spain. Some researchers believe that it is a candidate for common ancestor to the great ape clade, or is at least closer than any previous fossil discovery. Others suggest it being a pongine, or a dryopith. On 16 October 2023, scientists reported the facial reconstruction of the great ape.

Ouranopithecus is a genus of extinct Eurasian great ape represented by two species, Ouranopithecus macedoniensis, a late Miocene hominoid from Greece and Ouranopithecus turkae, also from the late Miocene of Turkey.

Nakalipithecus nakayamai, sometimes referred to as the Nakali ape, is an extinct species of great ape from Nakali, Kenya, from about 9.9–9.8 million years ago during the Late Miocene. It is known from a right jawbone with 3 molars and from 11 isolated teeth. The jawbone specimen is presumed female as the teeth are similar in size to those of female gorillas and orangutans. Compared to other great apes, the canines are short, the enamel is thin, and the molars are flatter. Nakalipithecus seems to have inhabited a sclerophyllous woodland environment.

Lufengpithecus is an extinct genus of ape, known from the Late Miocene of East Asia. It is known from thousands of dental remains and a few skulls and probably weighed about 50 kg (110 lb). It contains three species: L. lufengensis, L. hudienensis and L. keiyuanensis. Lufengpithecus lufengensis is from the Late Miocene found in China, named after the Lufeng site and dated around 6.2 Ma. Lufengpithecus is either thought to be the sister group to Ponginae, or the sister to the clade containing Ponginae and Homininae.

The Hominidae, whose members are known as the great apes or hominids, are a taxonomic family of primates that includes eight extant species in four genera: Pongo ; Gorilla ; Pan ; and Homo, of which only modern humans remain.

Anoiapithecus is an extinct ape genus thought to be closely related to Dryopithecus. Both genera lived during the Miocene, approximately 12 million years ago. Fossil specimens named by Salvador Moyà-Solà are known from the deposits from Spain.

Dryopithecini is an extinct tribe of Eurasian and African great apes that are believed to be close to the ancestry of gorillas, chimpanzees and humans. Members of this tribe are known as dryopithecines.

Morotopithecus is a genus of fossil ape discovered in Miocene-age deposits of Moroto, Uganda.

Hominid dispersals in Europe refers to the colonisation of the European continent by various species of hominid, including hominins and archaic and modern humans.

Nacholapithecus kerioi was an ape that lived 14-15 million years ago during the Middle Miocene. Fossils have been found in the Nachola formation in northern Kenya. The only member of the genus Nacholapithecus, it is thought to be a key genus in early hominid evolution. Similar in body plan to Proconsul, it had a long vertebral column with six lumbar vertebrae, no tail, a narrow torso, large upper limbs with mobile shoulder joints, and long feet.

Graecopithecus is an extinct genus of hominid that lived in southeast Europe during the late Miocene around 7.2 million years ago. Originally identified by a single lower jawbone bearing teeth found in Pyrgos Vasilissis, Athens, Greece, in 1944, other teeth were discovered from Azmaka quarry in Bulgaria in 2012. With only little and badly preserved materials to reveal its nature, it is considered as "the most poorly known European Miocene hominoids." The creature was popularly nicknamed 'El Graeco' by scientists.

Hispanopithecus is a genus of apes that inhabited Europe during the Miocene epoch. It was first identified in a 1944 paper by J. F. Villalta and M. Crusafont in Notas y Comunicaciones del Instituto Geologico y Minero de España. Anthropologists disagree as to whether Hispanopithecus belongs to the subfamily Ponginae or Homininae.

The phylogenetic split of Hominidae into the subfamilies Homininae and Ponginae is dated to the middle Miocene, roughly 18 to 14 million years ago. This split is also referenced as the "orangutan–human last common ancestor" by Jeffrey H. Schwartz, professor of anthropology at the University of Pittsburgh School of Arts and Sciences, and John Grehan, director of science at the Buffalo Museum.

Pliobates cataloniae is a primate from 11.6 million years ago, during the Iberian Miocene. Originally described as a species of stem-ape that was found to be the sister taxon to gibbons and great apes like humans, it was subsequently reinterpreted as a non-ape catarrhine belonging to the group Crouzeliidae within the superfamily Pliopithecoidea on the basis of discovery of new dental remains with crouzeliid synapomorphies.

Pliopithecoidea is an extinct superfamily of catarrhine primates that inhabited Asia and Europe during the Miocene. Although they were once a widespread and diverse group of primates, the pliopithecoids have no living descendants.

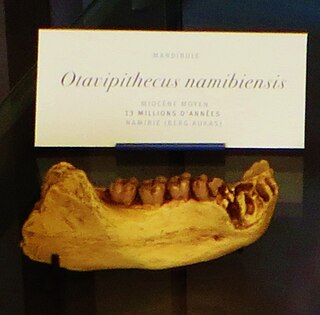

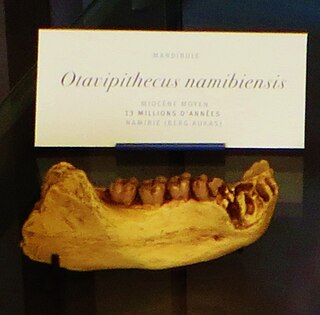

Otavipithecus namibiensis is an extinct species of ape from the Miocene of Namibia. The fossils were discovered at the Berg Aukas mines in the foothills of the Otavi mountains, hence the generic name. The species was described in 1992 by Glenn Conroy and colleagues, and was at the time the only non-hominin fossil ape known from Southern Africa. The scientists noted that the surrounding area of the discovered specimen included fauna dated at "about 13 ± 1 Myr". The fossils consist of part of the lower jawbone with molars, a partial frontal bone, a heavily damaged ulna, one vertebra and a partial finger bone.

Danuvius guggenmosi is an extinct species of great ape that lived 11.6 million years ago during the Middle–Late Miocene in southern Germany. It is the sole member of the genus Danuvius. The area at this time was probably a woodland with a seasonal climate. A male specimen was estimated to have weighed about 31 kg (68 lb), and two females 17 and 19 kg. Both genus and species were described in November 2019.