Alcoholism is the continued drinking of alcohol despite it causing problems. Some definitions require evidence of dependence and withdrawal. Problematic use of alcohol has been mentioned in the earliest historical records. The World Health Organization (WHO) estimated there were 283 million people with alcohol use disorders worldwide as of 2016. The term alcoholism was first coined in 1852, but alcoholism and alcoholic are stigmatizing and discourage seeking treatment, so clinical diagnostic terms such as alcohol use disorder or alcohol dependence are used instead.

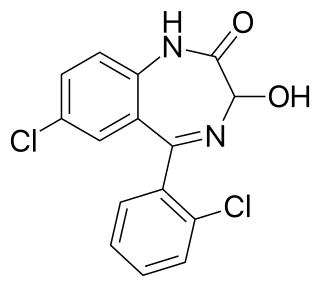

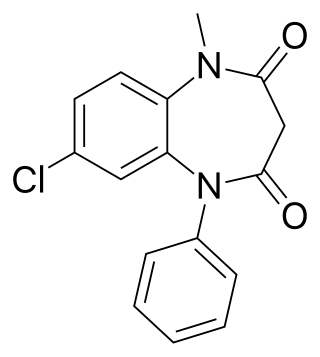

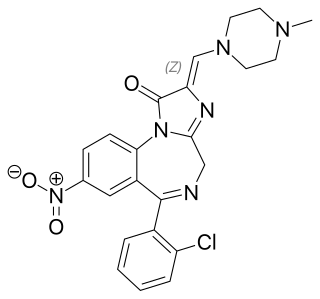

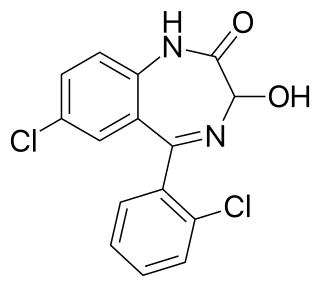

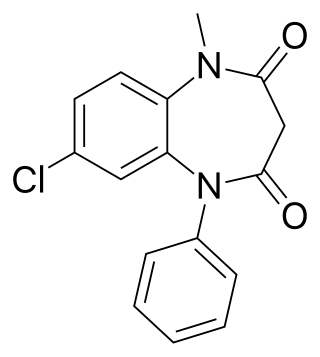

Benzodiazepines, colloquially called "benzos", are a class of depressant drugs whose core chemical structure is the fusion of a benzene ring and a diazepine ring. They are prescribed to treat conditions such as anxiety disorders, insomnia, and seizures. The first benzodiazepine, chlordiazepoxide (Librium), was discovered accidentally by Leo Sternbach in 1955, and was made available in 1960 by Hoffmann–La Roche, which followed with the development of diazepam (Valium) three years later, in 1963. By 1977, benzodiazepines were the most prescribed medications globally; the introduction of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), among other factors, decreased rates of prescription, but they remain frequently used worldwide.

Diazepam, sold under the brand name Valium among others, is a medicine of the benzodiazepine family that acts as an anxiolytic. It is used to treat a range of conditions, including anxiety, seizures, alcohol withdrawal syndrome, muscle spasms, insomnia, and restless legs syndrome. It may also be used to cause memory loss during certain medical procedures. It can be taken orally, as a suppository inserted into the rectum, intramuscularly, intravenously or used as a nasal spray. When injected intravenously, effects begin in one to five minutes and last up to an hour. When taken by mouth, effects begin after 15 to 60 minutes.

Lorazepam, sold under the brand name Ativan among others, is a benzodiazepine medication. It is used to treat anxiety, trouble sleeping, severe agitation, active seizures including status epilepticus, alcohol withdrawal, and chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting. It is also used during surgery to interfere with memory formation and to sedate those who are being mechanically ventilated. It is also used, along with other treatments, for acute coronary syndrome due to cocaine use. It can be given orally, transdermal, intravenously (IV), or intramuscularly When given by injection, onset of effects is between one and thirty minutes and effects last for up to a day.

Colloquially known as "downers", depressants or central depressants are drugs that lower neurotransmission levels, or depress or reduce arousal or stimulation in various areas of the brain. Depressants do not change the mood or mental state of others. Stimulants, or "uppers", increase mental or physical function, hence the opposite drug class from depressants are stimulants, not antidepressants.

Clonazepam, sold under the brand names Klonopin and Rivotril, is a medication used to prevent and treat anxiety disorders, seizures, bipolar mania, agitation associated with psychosis, OCD and akathisia. It is a long-acting tranquilizer of the benzodiazepine class. It possesses anxiolytic, anticonvulsant, sedative, hypnotic, and skeletal muscle relaxant properties. It is typically taken by mouth but is also used intravenously. Effects begin within one hour and last between eight and twelve hours in adults.

Bromazepam, sold under many brand names, is a benzodiazepine. It is mainly an anti-anxiety agent with similar side effects to diazepam. In addition to being used to treat anxiety or panic states, bromazepam may be used as a premedicant prior to minor surgery. Bromazepam typically comes in doses of 3 mg and 6 mg tablets.

Physical dependence is a physical condition caused by chronic use of a tolerance-forming drug, in which abrupt or gradual drug withdrawal causes unpleasant physical symptoms. Physical dependence can develop from low-dose therapeutic use of certain medications such as benzodiazepines, opioids, stimulants, antiepileptics and antidepressants, as well as the recreational misuse of drugs such as alcohol, opioids and benzodiazepines. The higher the dose used, the greater the duration of use, and the earlier age use began are predictive of worsened physical dependence and thus more severe withdrawal syndromes. Acute withdrawal syndromes can last days, weeks or months. Protracted withdrawal syndrome, also known as post-acute-withdrawal syndrome or "PAWS", is a low-grade continuation of some of the symptoms of acute withdrawal, typically in a remitting-relapsing pattern, often resulting in relapse and prolonged disability of a degree to preclude the possibility of lawful employment. Protracted withdrawal syndrome can last for months, years, or depending on individual factors, indefinitely. Protracted withdrawal syndrome is noted to be most often caused by benzodiazepines. To dispel the popular misassociation with addiction, physical dependence to medications is sometimes compared to dependence on insulin by persons with diabetes.

Clobazam, sold under the brand names Frisium, Onfi and others, is a benzodiazepine class medication that was patented in 1968. Clobazam was first synthesized in 1966 and first published in 1969. Clobazam was originally marketed as an anxioselective anxiolytic since 1970, and an anticonvulsant since 1984. The primary drug-development goal was to provide greater anxiolytic, anti-obsessive efficacy with fewer benzodiazepine-related side effects.

Clorazepate, sold under the brand name Tranxene among others, is a benzodiazepine medication. It possesses anxiolytic, anticonvulsant, sedative, hypnotic, and skeletal muscle relaxant properties. Clorazepate is an unusually long-lasting benzodiazepine and serves as a prodrug for the equally long-lasting desmethyldiazepam, which is rapidly produced as an active metabolite. Desmethyldiazepam is responsible for most of the therapeutic effects of clorazepate.

Acamprosate, sold under the brand name Campral, is a medication which reduces alcoholism cravings. It is thought to stabilize chemical signaling in the brain that would otherwise be disrupted by alcohol withdrawal. When used alone, acamprosate is not an effective therapy for alcohol use disorder in most individuals, as it only addresses withdrawal symptoms and not psychological dependence. It facilitates a reduction in alcohol consumption as well as full abstinence when used in combination with psychosocial support or other drugs that address the addictive behavior.

Organic brain syndrome, also known as organic brain disease, organic brain damage, organic brain disorder, organic mental syndrome, or organic mental disorder, refers to any syndrome or disorder of mental function whose cause is alleged to be known as organic (physiologic) rather than purely of the mind. These names are older and nearly obsolete general terms from psychiatry, referring to many physical disorders that cause impaired mental function. They are meant to exclude psychiatric disorders. Originally, the term was created to distinguish physical causes of mental impairment from psychiatric disorders, but during the era when this distinction was drawn, not enough was known about brain science for this cause-based classification to be more than educated guesswork labeled with misplaced certainty, which is why it has been deemphasized in current medicine. While mental or behavioural abnormalities related to the dysfunction can be permanent, treating the disease early may prevent permanent damage in addition to fully restoring mental functions. An organic cause to brain dysfunction is suspected when there is no indication of a clearly defined psychiatric or "inorganic" cause, such as a mood disorder.

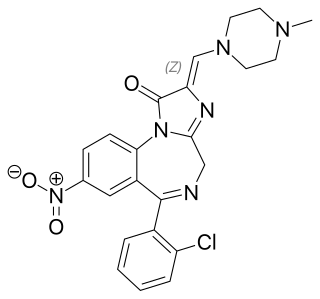

Loprazolam (triazulenone) marketed under many brand names is a benzodiazepine medication. It possesses anxiolytic, anticonvulsant, hypnotic, sedative and skeletal muscle relaxant properties. It is licensed and marketed for the short-term treatment of moderately-severe insomnia.

Delirium tremens is a rapid onset of confusion usually caused by withdrawal from alcohol. When it occurs, it is often three days into the withdrawal symptoms and lasts for two to three days. Physical effects may include shaking, shivering, irregular heart rate, and sweating. People may also hallucinate. Occasionally, a very high body temperature or seizures may result in death. Alcohol is one of the more dangerous drugs to withdraw from.

Benzodiazepine withdrawal syndrome is the cluster of signs and symptoms that may emerge when a person who has been taking benzodiazepines as prescribed develops a physical dependence on them and then reduces the dose or stops taking them without a safe taper schedule.

Alcohol detoxification is the abrupt cessation of alcohol intake in individuals that have alcohol use disorder. This process is often coupled with substitution of drugs that have effects similar to the effects of alcohol in order to lessen the symptoms of alcohol withdrawal. When withdrawal does occur, it results in symptoms of varying severity.

Post-acute withdrawal syndrome (PAWS) is a hypothesized set of persistent impairments that occur after withdrawal from alcohol, opiates, benzodiazepines, antidepressants, and other substances. Infants born to mothers who used substances of dependence during pregnancy may also experience a PAWS. While PAWS has been frequently reported by those withdrawing from opiate and alcohol dependence, the research has limitations. Protracted benzodiazepine withdrawal has been observed to occur in some individuals prescribed benzodiazepines.

Alcoholic hallucinosis is a complication of alcohol misuse in people with alcohol use disorder. It can occur during acute intoxication or withdrawal with the potential of having delirium tremens. Alcohol hallucinosis is a rather uncommon alcohol-induced psychotic disorder almost exclusively seen in chronic alcoholics who have many consecutive years of severe and heavy drinking during their lifetime. Alcoholic hallucinosis develops about 12 to 24 hours after the heavy drinking stops suddenly, and can last for days. It involves auditory and visual hallucinations, most commonly accusatory or threatening voices. The risk of developing alcoholic hallucinosis is increased by long-term heavy alcohol abuse and the use of other drugs. Descriptions of the condition date back to at least 1907.

Benzodiazepine dependence defines a situation in which one has developed one or more of either tolerance, withdrawal symptoms, drug seeking behaviors, such as continued use despite harmful effects, and maladaptive pattern of substance use, according to the DSM-IV. In the case of benzodiazepine dependence, the continued use seems to be typically associated with the avoidance of unpleasant withdrawal reaction rather than with the pleasurable effects of the drug. Benzodiazepine dependence develops with long-term use, even at low therapeutic doses, often without the described drug seeking behavior and tolerance.

Kindling due to substance withdrawal is the neurological condition which results from repeated withdrawal episodes from sedative–hypnotic drugs such as alcohol and benzodiazepines.