Related Research Articles

An antiemetic is a drug that is effective against vomiting and nausea. Antiemetics are typically used to treat motion sickness and the side effects of opioid analgesics, general anaesthetics, and chemotherapy directed against cancer. They may be used for severe cases of gastroenteritis, especially if the patient is dehydrated.

The effects of cannabis are caused by chemical compounds in the cannabis plant, including 113 different cannabinoids such as tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) and 120 terpenes, which allow its drug to have various psychological and physiological effects on the human body. Different plants of the genus Cannabis contain different and often unpredictable concentrations of THC and other cannabinoids and hundreds of other molecules that have a pharmacological effect, so the final net effect cannot reliably be foreseen.

Medical cannabis, or medical marijuana (MMJ), is cannabis and cannabinoids that are prescribed by physicians for their patients. The use of cannabis as medicine has not been rigorously tested due to production and governmental restrictions, resulting in limited clinical research to define the safety and efficacy of using cannabis to treat diseases.

Morning sickness, also called nausea and vomiting of pregnancy (NVP), is a symptom of pregnancy that involves nausea or vomiting. Despite the name, nausea or vomiting can occur at any time during the day. Typically the symptoms occur between the 4th and 16th week of pregnancy. About 10% of women still have symptoms after the 20th week of pregnancy. A severe form of the condition is known as hyperemesis gravidarum and results in weight loss.

Functional gastrointestinal disorders (FGID), also known as disorders of gut–brain interaction, include a number of separate idiopathic disorders which affect different parts of the gastrointestinal tract and involve visceral hypersensitivity and motility disturbances.

Ondansetron, sold under the brand name Zofran among others, is a medication used to prevent nausea and vomiting caused by cancer chemotherapy, radiation therapy, migraines or surgery. It is also effective for treating gastroenteritis. It can be given orally, intramuscularly, or intravenously.

Cyclic vomiting syndrome (CVS) is a chronic functional condition of unknown pathogenesis. CVS is characterized as recurring episodes lasting a single day to multiple weeks. Each episode is divided into four phases: inter-episodic, prodrome, vomiting, and recovery. Inter-episodic phase, is characterized as no discernible symptoms, normal everyday activities can occur, and this phase typically lasts one week to one month. The prodrome phase is known as the pre-emetic phase, characterized by the initial feeling of an approaching episode, still able to keep down oral medication. Emetic or vomiting phase is characterized as intense persistent nausea, and repeated vomiting typically lasting hours to days. Recovery phase is typically the phase where vomiting ceases, nausea diminishes or is absent, and appetite returns. "Cyclic vomiting syndrome (CVS) is a rare abnormality of the neuroendocrine system that affects 2% of children." This disorder is thought to be closely related to migraines and family history of migraines.

Aprepitant, sold under the brand name Emend among others, is a medication used to prevent chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting (CINV) and to prevent postoperative nausea and vomiting (PONV). It may be used together with ondansetron and dexamethasone. It is taken by mouth or administered by intravenous injection.

Nabilone, sold under the brand name Cesamet among others, is a synthetic cannabinoid with therapeutic use as an antiemetic and as an adjunct analgesic for neuropathic pain. It mimics tetrahydrocannabinol (THC), the primary psychoactive compound found naturally occurring in Cannabis.

Hyperemesis gravidarum (HG) is a pregnancy complication that is characterized by severe nausea, vomiting, weight loss, and possibly dehydration. Feeling faint may also occur. It is considered more severe than morning sickness. Symptoms often get better after the 20th week of pregnancy but may last the entire pregnancy duration.

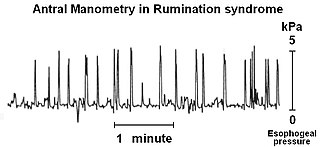

Rumination syndrome, or merycism, is a chronic motility disorder characterized by effortless regurgitation of most meals following consumption, due to the involuntary contraction of the muscles around the abdomen. There is no retching, nausea, heartburn, odour, or abdominal pain associated with the regurgitation as there is with typical vomiting, and the regurgitated food is undigested. The disorder has been historically documented as affecting only infants, young children, and people with cognitive disabilities . It is increasingly being diagnosed in a greater number of otherwise healthy adolescents and adults, though there is a lack of awareness of the condition by doctors, patients, and the general public.

Levonantradol (CP 50,556-1) is a synthetic cannabinoid analog of dronabinol (Marinol) developed by Pfizer in the 1980s. It is around 30 times more potent than THC, and exhibits antiemetic and analgesic effects via activation of CB1 and CB2 cannabinoid receptors. Levonantradol is not currently used in medicine as dronabinol or nabilone are felt to be more useful for most conditions, however it is widely used in research into the potential therapeutic applications of cannabinoids.

The Rome process and Rome criteria are an international effort to create scientific data to help in the diagnosis and treatment of functional gastrointestinal disorders, such as irritable bowel syndrome, functional dyspepsia and rumination syndrome. The Rome diagnostic criteria are set forth by Rome Foundation, a not for profit 501(c)(3) organization based in Raleigh, North Carolina, United States.

Vomiting is the involuntary, forceful expulsion of the contents of one's stomach through the mouth and sometimes the nose.

Nausea is a diffuse sensation of unease and discomfort, sometimes perceived as an urge to vomit. While not painful, it can be a debilitating symptom if prolonged and has been described as placing discomfort on the chest, abdomen, or back of the throat.

Abdominal aura, also known as visceral aura and epigastric aura, is a type of somatosensory aura that typically manifests as abdominal discomfort in the form of nausea, malaise, hunger, or pain. Abdominal aura is typically associated with epilepsy, especially temporal lobe epilepsy, and it can also be used in the context of migraine. The term is used to distinguish it from other types of somatosensory aura, notably visual disturbances and paraesthesia. The abdominal aura can be classified as a somatic hallucination. Pathophysiologically, the abdominal aura is associated with aberrant neuronal discharges in sensory cortical areas representing the abdominal viscera.

Chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting (CINV) is a common side-effect of many cancer treatments. Nausea and vomiting are two of the most feared cancer treatment-related side effects for cancer patients and their families. In 1983, Coates et al. found that patients receiving chemotherapy ranked nausea and vomiting as the first and second most severe side effects, respectively. Up to 20% of patients receiving highly emetogenic agents in this era postponed, or even refused, potentially curative treatments. Since the 1990s, several novel classes of antiemetics have been developed and commercialized, becoming a nearly universal standard in chemotherapy regimens, and helping to better manage these symptoms in a large portion of patients. Efficient mediation of these unpleasant and sometimes debilitating symptoms results in increased quality of life for the patient, and better overall health of the patient, and, due to better patient tolerance, more effective treatment cycles.

Abdominal migraine(AM) is a functional disorder that usually manifests in childhood and adolescence, without a clear pathologic mechanism or biochemical irregularity. Children frequently experience sporadic episodes of excruciating central abdominal pain accompanied by migrainous symptoms like nausea, vomiting, severe headaches, and general pallor. Abdominal migraine can be diagnosed based off clinical criteria and the exclusion of other disorders.

Cancer and nausea are associated in about fifty percent of people affected by cancer. This may be as a result of the cancer itself, or as an effect of the treatment such as chemotherapy, radiation therapy, or other medication such as opiates used for pain relief. About 70 to 80% of people undergoing chemotherapy experience nausea or vomiting. Nausea and vomiting may also occur in people not receiving treatment, often as a result of the disease involving the gastrointestinal tract, electrolyte imbalance, or as a result of anxiety. Nausea and vomiting may be experienced as the most unpleasant side effects of cytotoxic drugs and may result in patients delaying or refusing further radiotherapy or chemotherapy.

Cannabis consumption in pregnancy may or may not be associated with restrictions in growth of the fetus, miscarriage, and cognitive deficits. The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists recommended that cannabis use be stopped before and during pregnancy. There has not been any official link between birth defects and marijuana use. Cannabis is the most commonly used illicit substance among pregnant women.

References

- 1 2 Sullivan S (May 2010). "Cannabinoid hyperemesis". Canadian Journal of Gastroenterology. 24 (5): 284–5. doi: 10.1155/2010/481940 . PMC 2886568 . PMID 20485701.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Korn F, Hammerich S, Gries A (February 2021). "Cannabinoidhyperemesis als Differenzialdiagnose von Übelkeit und Erbrechen in der Notaufnahme". Der Anaesthesist (Review) (in German). 70 (2): 158–160. doi:10.1007/s00101-020-00850-2. PMC 7850992 . PMID 33090239.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 Galli JA, Sawaya RA, Friedenberg FK (December 2011). "Cannabinoid hyperemesis syndrome". Current Drug Abuse Reviews. 4 (4): 241–9. doi:10.2174/1874473711104040241. PMC 3576702 . PMID 22150623.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Sorensen CJ, DeSanto K, Borgelt L, Phillips KT, Monte AA (20 December 2016). "Cannabinoid Hyperemesis Syndrome: Diagnosis, Pathophysiology, and Treatment—a Systematic Review". Journal of Medical Toxicology. 13 (1): 71–87. doi:10.1007/s13181-016-0595-z. PMC 5330965 . PMID 28000146.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 DeVuono M, Parker L (2020). "Cannabinoid Hyperemesis Syndrome: A Review of Potential Mechanisms". Cannabis and Cannabinoid Research. 5 (2): 132–144. doi:10.1089/can.2019.0059. PMC 7347072 . PMID 32656345.

- 1 2 3 4 5 [ unreliable medical source? ]Chocron Y, Zuber JP, Vaucher J (19 July 2019). "Cannabinoid hyperemesis syndrome". BMJ (Clinical Research Ed.). 366: l4336. doi:10.1136/bmj.l4336. PMID 31324702. S2CID 198133206.

- ↑ Sorensen CJ, DeSanto K, Borgelt L, Phillips KT, Monte AA (March 2017). "Cannabinoid Hyperemesis Syndrome: Diagnosis, Pathophysiology, and Treatment—a Systematic Review". Journal of Medical Toxicology. 13 (1): 71–87. doi:10.1007/s13181-016-0595-z. ISSN 1556-9039. PMC 5330965 . PMID 28000146.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 Sun S, Zimmermann AE (September 2013). "Cannabinoid hyperemesis syndrome". Hospital Pharmacy. 48 (8): 650–5. doi:10.1310/hpj4808-650. PMC 3847982 . PMID 24421535.

- ↑ Venkatesan T, Levinthal DJ, Tarbell SE, Jaradeh SS, Hasler WL, Issenman RM, et al. (June 2019). "Guidelines on management of cyclic vomiting syndrome in adults by the American Neurogastroenterology and Motility Society and the Cyclic Vomiting Syndrome Association". Neurogastroenterology & Motility. 31 (S2): e13604. doi:10.1111/nmo.13604. ISSN 1350-1925. PMC 6899751 . PMID 31241819.

- ↑ Rotella JA, Ferretti OG, Raisi E, Seet HR, Sarkar S (August 2022). "Cannabinoid hyperemesis syndrome: A 6-year audit of adult presentations to an urban district hospital". Emergency Medicine Australasia. 34 (4): 578–583. doi:10.1111/1742-6723.13944. ISSN 1742-6731. PMC 9545654 . PMID 35199462.

- 1 2 Allen JH, De Moore GM, Heddle R, Twartz JC (2004). "Cannabinoid hyperemesis: Cyclical hyperemesis in association with chronic cannabis abuse". Gut. 53 (11): 1566–70. doi:10.1136/gut.2003.036350. PMC 1774264 . PMID 15479672.

- 1 2 Sontineni SP, Chaudhary S, Sontineni V, Lanspa SJ (2009). "Cannabinoid hyperemesis syndrome: Clinical diagnosis of an underrecognized manifestation of chronic cannabis abuse". World Journal of Gastroenterology. 15 (10): 1264–6. doi: 10.3748/wjg.15.1264 . PMC 2658859 . PMID 19291829.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Ruffle JK, Bajgoric S, Samra K, Chandrapalan S, Aziz Q, Farmer AD (December 2015). "Cannabinoid hyperemesis syndrome". European Journal of Gastroenterology & Hepatology. 27 (12): 1403–1408. doi:10.1097/MEG.0000000000000489. PMID 26445382. S2CID 23685653.

- ↑ Rotella JA, Ferretti OG, Raisi E, Seet HR, Sarkar S (August 2022). "Cannabinoid hyperemesis syndrome: A 6-year audit of adult presentations to an urban district hospital". Emergency Medicine Australasia. 34 (4): 578–583. doi:10.1111/1742-6723.13944. ISSN 1742-6731. PMC 9545654 . PMID 35199462.

- 1 2 3 Knowlton MC (October 2019). "Cannabinoid hyperemesis syndrome". Nursing. 49 (10): 42–45. doi:10.1097/01.NURSE.0000577992.82047.67. PMID 31568081. S2CID 203623679.

- ↑ Nourbakhsh M, Miller A, Gofton J, Jones G, Adeagbo B (16 May 2018). "Cannabinoid Hyperemesis Syndrome: Reports of Fatal Cases". Journal of Forensic Sciences. 64 (1). Wiley: 270–274. doi: 10.1111/1556-4029.13819 . ISSN 0022-1198. PMID 29768651. S2CID 21718690.

- 1 2 3 Hasler WL, Levinthal DJ, Tarbell SE, Adams KA, Li BU, Issenman RM, et al. (June 2019). "Cyclic vomiting syndrome: Pathophysiology, comorbidities, and future research directions". Neurogastroenterol Motil (Review). 31 (Suppl 2): e13607. doi: 10.1111/nmo.13607 . PMC 6899706 . PMID 31241816.

- ↑ Burillo-Putze G, Richards J, Rodríguez-Jiménez C, Sanchez-Agüera A (April 2022). "Pharmacological management of cannabinoid hyperemesis syndrome: an update of the clinical literature". Expert Opin Pharmacother. 23 (6): 693–702. doi:10.1080/14656566.2022.2049237. PMID 35311429. S2CID 247584469 – via PMID 35311429.

- ↑ Russo E, Spooner C, May L, Leslie R, Whiteley V (July 2021). "Cannabinoid Hyperemesis Syndrome Survey and Genomic Investigation". Cannabis and Cannabinoid Research. 7 (3): 336–344. doi:10.1089/can.2021.0046. PMC 9225400 . PMID 34227878. S2CID 235744908. Archived from the original on 3 July 2022. Retrieved 6 April 2022.

- 1 2 Senderovich H, Patel P, Jimenez Lopez B, Waicus S (2022). "A Systematic Review on Cannabis Hyperemesis Syndrome and Its Management Options". Medical Principles and Practice. 31 (1): 29–38. doi:10.1159/000520417. ISSN 1011-7571. PMC 8995641 . PMID 34724666.

- 1 2 3 4 DeVuono MV, Parker LA (1 June 2020). "Cannabinoid Hyperemesis Syndrome: A Review of Potential Mechanisms". Cannabis and Cannabinoid Research. 5 (2): 132–144. doi:10.1089/can.2019.0059. ISSN 2578-5125. PMC 7347072 . PMID 32656345.

- ↑ Eskridge KD, Guthrie SK (6 May 1997). "Clinical Issues Associated with Urine Testing of Substances of Abuse". Pharmacotherapy: The Journal of Human Pharmacology and Drug Therapy. 17 (3): 497–510. doi:10.1002/j.1875-9114.1997.tb03059.x. hdl: 2027.42/90147 . ISSN 0277-0008. PMID 9165553. S2CID 23295770.

- ↑ Richards JR, Gordon BK, Danielson AR, Moulin AK (June 2017). "Pharmacologic Treatment of Cannabinoid Hyperemesis Syndrome: A Systematic Review". Pharmacotherapy. 37 (6): 725–734. doi: 10.1002/phar.1931 . ISSN 1875-9114. PMID 28370228.

- ↑ Wallace EA, Andrews SE, Garmany CL, Jelley MJ (1 September 2011). "Cannabinoid hyperemesis syndrome: literature review and proposed diagnosis and treatment algorithm". Southern Medical Journal. 104 (9): 659–664. doi:10.1097/SMJ.0b013e3182297d57. PMID 21886087.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Lapoint J, Meyer S, Yu C, Koenig K, Lev R, Thihalolipavan S, et al. (2018). "Cannabinoid Hyperemesis Syndrome: Public Health Implications and a Novel Model Treatment Guideline". Western Journal of Emergency Medicine. 19 (2): 380–386. doi:10.5811/westjem.2017.11.36368. PMC 5851514 . PMID 29560069.

- ↑ Sorensen CJ, DeSanto K, Borgelt L, Phillips KT, Monte AA (March 2017). "Cannabinoid Hyperemesis Syndrome: Diagnosis, Pathophysiology, and Treatment—a Systematic Review". Journal of Medical Toxicology. 13 (1): 71–87. doi:10.1007/s13181-016-0595-z. ISSN 1556-9039. PMC 5330965 . PMID 28000146.

- 1 2 King C, Holmes A (17 March 2015). "Cannabinoid hyperemesis syndrome". Canadian Medical Association Journal. 187 (5): 355. doi:10.1503/cmaj.140154. PMC 4361109 . PMID 25183721.

- 1 2 3 Habboushe J, Rubin A, Liu H, Hoffman RS (June 2018). "The Prevalence of Cannabinoid Hyperemesis Syndrome Among Regular Marijuana Smokers in an Urban Public Hospital". Basic & Clinical Pharmacology & Toxicology. 122 (6): 660–662. doi:10.1111/bcpt.12962. ISSN 1742-7835. PMID 29327809.

- 1 2 Venkatesan T, Levinthal DJ, Li BU, Tarbell SE, Adams KA, Issenman RM, et al. (June 2019). "Role of chronic cannabis use: Cyclic vomiting syndrome vs cannabinoid hyperemesis syndrome". Neurogastroenterol Motil (Systematic review). 31 (Suppl 2): e13606. doi:10.1111/nmo.13606. PMC 6788295 . PMID 31241817.

- ↑ Lu ML, Agito MD (July 2015). "Cannabinoid hyperemesis syndrome: Marijuana is both antiemetic and proemetic". Cleveland Clinic Journal of Medicine. 82 (7): 429–34. doi: 10.3949/ccjm.82a.14023 . PMID 26185942. S2CID 25397379.

- ↑ Schreck B, Wagneur N, Caillet P, Gérardin M, Cholet J, Spadari M, et al. (January 2018). "Cannabinoid hyperemesis syndrome: Review of the literature and of cases reported to the French addictovigilance network". Drug Alcohol Depend (Review). 182: 27–32. doi:10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2017.09.038. PMID 29132050.

- ↑ https://www.jem-journal.com/article/S0736-4679(12)01472-2/abstract

- ↑ Brodwin E (15 February 2019). "A mysterious syndrome in which marijuana users get violently ill is starting to worry researchers". Business Insider. Archived from the original on 14 May 2019. Retrieved 26 March 2019.

- ↑ Rabin R (9 April 2018). "Marjuana linked to 'unbearable' sickness across US as use grows following legalisation". The Independent. Archived from the original on 10 May 2018. Retrieved 10 May 2018.

- 1 2 Bartolone P. "'I've screamed out for death': Heavy, long-term pot use linked to rare, extreme nausea". USA TODAY. Archived from the original on 10 May 2018. Retrieved 10 May 2018.

- ↑ "Scromiting: The Unpleasant And Occasionally Deadly Illness Linked To Using Weed". IFLScience . 13 July 2021. Archived from the original on 25 January 2022. Retrieved 25 January 2022.

- ↑ "FACT CHECK: Can Marijuana Use Lead to Simultaneous Screaming and Vomiting?". Snopes.com . 2017. Archived from the original on 25 January 2022. Retrieved 25 January 2022.