Ancestry by race

Hobbit family trees

| A Small Part [lower-alpha 1] of the Genealogy of the Baggins Family of Hobbits, from Appendix C of The Lord of the Rings , [T 2] annotated to show the inheritance of character [4] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Tolkien's Middle-earth family trees have multiple functions, including establishing the characters' lineages and the relationships between them, and helping to create an impression of depth. [4] Apart from these, a key function is to show how different ancestries, and hence in Tolkien's view different aspects of character, come together in his protagonists. [4] [5] [6] The Tolkien scholar Jason Fisher explains that the apparently home-loving but in fact also adventurous and resourceful Bilbo Baggins, for instance, was born to a genteel Baggins and an adventurous Took, while his similarly conflicted cousin (often familiarly described as his nephew) and heir Frodo was the child of a Baggins and a relatively outlandish Brandybuck. [4] Thus, character is explained and predicted by ancestry. [4] Tolkien has his Hobbits share this belief; families were important to them, and they were extremely fond of studying their own genealogy, as illustrated, too, by the multiple Hobbit family trees in the appendices of The Lord of the Rings. [4] Tolkien stated directly in the prologue: [T 3]

All hobbits were, in any case, clannish and reckoned up their relationships with great care. They drew long and elaborate family-trees with innumerable branches. In dealing with hobbits it is important to remember who is related to whom, and in what degree. [T 3]

The ancestry of Bilbo and Frodo involved the Boffin and Bolger families alongside the better-known Tooks and Brandybucks. Tolkien had drawn up family trees for the Boffins and Bolgers, providing additional background on the character of the central Hobbit figures, but these were left out of the appendices to save space. [lower-alpha 2] [7]

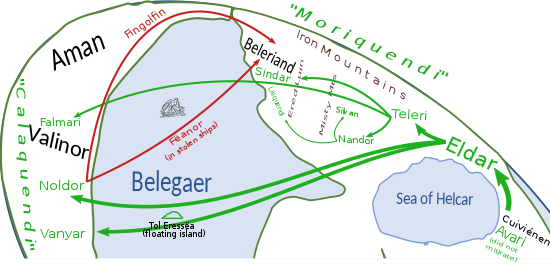

Elvish splinterings

In the long and complex process of the Sundering of the Elves, Tolkien consistently shows that the highest Elves are those who deviated least from their initial uncorrupted state: they complied with the will of the Valar, travelled to the blessed realm of Valinor where they saw the light of the Two Trees, and continued to speak the highest language, Quenya. Conversely, the lowest Elves, the Avari, refused to make the journey, never saw the light, and fragmented into many kindreds with different languages as they eventually spread out across Middle-earth. The Tolkien scholars Tom Shippey and Verlyn Flieger both note that Tolkien thus intended ancestry to be a guide to character. The differences between the various Elvish languages mirror both the Sundering and the events of The Silmarillion . [9] [5] [6]

Flieger states that the three major groups of Elves who set out on the journey to Valinor, the Eldar, each had their own character, which the reader needs to grasp to understand what drives the protagonists of The Silmarillion, by way of their personal membership of one or more of these groups. [10]

| Group | History | Character from history |

|---|---|---|

| Vanyar | First to set out, stay in Valinor for ever after arriving; close to the godlike Valar | Highest of the Elves; settled in the light and in themselves |

| Noldor | Set out next, go to Valinor and leave again | Torn both ways, creative, artistic, seeking knowledge, skilful, loving words, with potential for both good and ill |

| Teleri | Last to set out, least eager for the light, most numerous | "Vacillate, hesitate, are changeful in mind and spirit"; they are "the Singers", love water, always live by it, are mutable |

Shippey writes that The Silmarillion echoes Norse mythology in its belief that character is determined by ancestry, and that one perhaps needs to study the family trees to see clearly how it all works. He gives the example of Fëanor, the impetuous creator of the Silmarils , and his relatives: [5]

| Person | Ancestry | Character from ancestry |

|---|---|---|

| Fëanor | pure Noldor from both father and mother | Creative, headstrong, selfish |

| Fëanor's half-brothers Finarfin and Fingolfin | mother is of "'senior' race", Vanyar | "Superior" to Fëanor "in restraint and generosity" |

| Finarfin's children Finrod and Galadriel | mother is of "junior" race, Teleri | Relatively sympathetic |

| Fingolfin's children, e.g. Aredhel | "mixed Noldor/Vanyar" | "Reckless" |

| Fëanor's sons | pure Noldor | Aggressive, unsympathetic |

Shippey comments that one way to read The Silmarillion is to assume that "'character' is in a sense fixed, static, even diagrammatic." [5] He states that this was a common belief in medieval times, giving the example of the Old English proverb which asserts that "a man shows what he's like when he can do what he wants", i.e. their character was assumed to be built-in. Similarly in Norse mythology, the nature of each person in a saga is, Shippey writes, stated when they are introduced; the rest of the story just demonstrates how that plays out in practice. [5]

Mannish lineages

| Half-elven family tree [T 5] [T 6] | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Aragorn, hero of The Lord of the Rings , appears as a Man, and is described as such with the epithet Dúnadan, "Man of the West". His blood is however richer than that, as he can trace his ancestry back to the marriage of Eärendil and Elwing, both half-Elven and thus higher than mortal Men. Further, Elwing's ancestry goes back to the marriage of Thingol, the Elven King of Doriath, and Melian, a Maia or immortal spirit, one of the angelic Ainur. As far as his Elven pedigree is concerned, he was not only of the Teleri ("Those who come last") via Thingol; Eärendil was descended via Idril Celebrindal from Finwë of the Noldor ("Deep Elves") and Indis of the Vanyar ("The Fair"). [T 5] These two groups were the highest of the Elves, and unlike the Teleri kept the faith by migrating all the way to Aman and thus saw the light of the Two Trees of Valinor. [8] [T 7] Aragorn was thus not only of a long royal lineage, and not only with an admixture of Elvish blood: it was the best possible, being both from high Elves and Elvish kings. [12] [13]

The Tolkien scholar Angela Nicholas argues that Aragorn's combined Man, Elf, and Maia ancestry "infuses divinity into his character." [12] [14] Judy Ann Ford and Robin Anne Reid write in Tolkien Studies that while the destruction of the One Ring prevents Sauron from taking over the whole of Middle-earth, the "true king", Aragorn, is required "to restore the world of men to its former glory." [13] Aragorn has this destiny in his epithets, "for in the high tongue of old [Quenya] I am Elessar, the Elfstone, and Envinyatar, the Renewer'". [13] [T 8] Ford and Reid comment that Tolkien has made Aragorn conform to the Anglo-Saxon ideal of kingship, noting that their kings "claimed descent from [the god] Woden", and further that "This divine ancestry was believed to endow royal blood with a portion of divine wisdom and supernatural power." [13]

In his 2022 book Tolkien, Race, and Racism in Middle-earth, Robert Stuart on the other hand describes Tolkien's emphasis on Aragorn's ancestry as "aristocratic racism", likening Tolkien's implied views on race to those of the French 19th century diplomat Arthur de Gobineau, which he characterises as "anti-democratic, anti-national and, above all, anti-modern". [11]