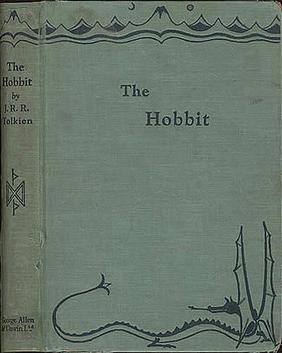

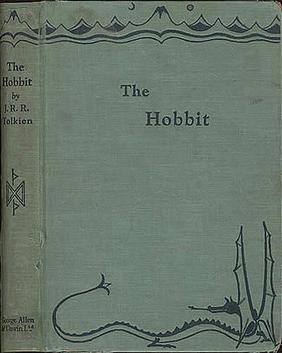

The Hobbit, or There and Back Again is a children's fantasy novel by English author J. R. R. Tolkien. It was published in 1937 to wide critical acclaim, being nominated for the Carnegie Medal and awarded a prize from the New York Herald Tribune for best juvenile fiction. The book is recognized as a classic in children's literature and is one of the best-selling books of all time, with over 100 million copies sold.

Rivendell is a valley in J. R. R. Tolkien's fictional world of Middle-earth, representing both a homely place of sanctuary and a magical Elvish otherworld. It is an important location in The Hobbit and The Lord of the Rings, being the place where the quest to destroy the One Ring began.

The following outline is provided as an overview of and topical guide to the real-world history and notable fictional elements of J. R. R. Tolkien's fantasy universe. It covers materials created by Tolkien; the works on his unpublished manuscripts, by his son Christopher Tolkien; and films, games and other media created by other people.

Scholars and critics have identified many themes of The Lord of the Rings, a major fantasy novel by J. R. R. Tolkien, including a reversed quest, the struggle of good and evil, death and immortality, fate and free will, the danger of power, and various aspects of Christianity such as the presence of three Christ figures, for prophet, priest, and king, as well as elements like hope and redemptive suffering. There is also a strong thread throughout the work of language, its sound, and its relationship to peoples and places, along with moralisation from descriptions of landscape. Out of these, Tolkien stated that the central theme is death and immortality.

"The Council of Elrond" is the second chapter of Book 2 of J. R. R. Tolkien's bestselling fantasy work, The Lord of the Rings, which was published in 1954–1955. It is the longest chapter in that book at some 15,000 words, and critical for explaining the power and threat of the One Ring, for introducing the final members of the Fellowship of the Ring, and for defining the planned quest to destroy it. Contrary to the maxim "Show, don't tell", the chapter consists mainly of people talking; the action is, as in an earlier chapter "The Shadow of the Past", narrated, largely by the Wizard Gandalf, in flashback. The chapter parallels the far simpler Beorn chapter in The Hobbit, which similarly presents a culture-clash of modern with ancient. The Tolkien scholar Tom Shippey calls the chapter "a largely unappreciated tour de force". The Episcopal priest Fleming Rutledge writes that the chapter brings the hidden narrative of Christianity in The Lord of the Rings close to the surface.

Aragorn is a fictional character and a protagonist in J. R. R. Tolkien's The Lord of the Rings. Aragorn was a Ranger of the North, first introduced with the name Strider and later revealed to be the heir of Isildur, an ancient King of Arnor and Gondor. Aragorn was a confidant of the wizard Gandalf, and played a part in the quest to destroy the One Ring and defeat the Dark Lord Sauron. As a young man, Aragorn fell in love with the immortal elf Arwen, as told in "The Tale of Aragorn and Arwen". Arwen's father, Elrond Half-elven, forbade them to marry unless Aragorn became King of both Arnor and Gondor.

Frodo Baggins is a fictional character in J. R. R. Tolkien's writings, and one of the protagonists in The Lord of the Rings. Frodo is a hobbit of the Shire who inherits the One Ring from his cousin Bilbo Baggins, described familiarly as "uncle", and undertakes the quest to destroy it in the fires of Mount Doom in Mordor. He is mentioned in Tolkien's posthumously published works, The Silmarillion and Unfinished Tales.

The naming of weapons in Middle-earth is the giving of names to swords and other powerful weapons in J. R. R. Tolkien's legendarium. He derived the naming of weapons from his knowledge of Medieval times; the practice is found in Norse mythology and in the Old English poem Beowulf. Among the many weapons named by Tolkien are Orcrist and Glamdring in The Hobbit, and Narsil / Andúril in The Lord of the Rings. Such weapons carry powerful symbolism, embodying the identity and ancestry of their owners.

Character pairing in The Lord of the Rings is a literary device used by J. R. R. Tolkien, a Roman Catholic, to express some of the moral complexity of his major characters in his heroic romance, The Lord of the Rings. Commentators have noted that the format of a fantasy does not lend itself to subtlety of characterisation, but that pairing allows inner tensions to be expressed as linked opposites, including, in a psychoanalytic interpretation, those of Jungian archetypes.

England and Englishness are represented in multiple forms within J. R. R. Tolkien's Middle-earth writings; it appears, more or less thinly disguised, in the form of the Shire and the lands close to it; in kindly characters such as Treebeard, Faramir, and Théoden; in its industrialised state as Isengard and Mordor; and as Anglo-Saxon England in Rohan. Lastly, and most pervasively, Englishness appears in the words and behaviour of the hobbits, both in The Hobbit and in The Lord of the Rings.

J. R. R. Tolkien, a fantasy author and professional philologist, drew on the Old English poem Beowulf for multiple aspects of his Middle-earth legendarium, alongside other influences. He used elements such as names, monsters, and the structure of society in a heroic age. He emulated its style, creating an impression of depth and adopting an elegiac tone. Tolkien admired the way that Beowulf, written by a Christian looking back at a pagan past, just as he was, embodied a "large symbolism" without ever becoming allegorical. He worked to echo the symbolism of life's road and individual heroism in The Lord of the Rings.

The philologist and author J. R. R. Tolkien set out to explore time travel and distortions in the passage of time in his fiction in a variety of ways. The passage of time in The Lord of the Rings is uneven, seeming to run at differing speeds in the realms of Men and of Elves. In this, Tolkien was following medieval tradition in which time proceeds differently in Elfland. The whole work, too, following the theory he spelt out in his essay "On Fairy-Stories", is meant to transport the reader into another time. He built a process of decline and fall in Middle-earth into the story, echoing the sense of impending destruction of Norse mythology. The Elves attempt to delay this decline as far as possible in their realms of Rivendell and Lothlórien, using their Rings of Power to slow the passage of time. Elvish time, in The Lord of the Rings as in the medieval Thomas the Rhymer and the Danish Elvehøj, presents apparent contradictions. Both the story itself and scholarly interpretations offer varying attempts to resolve these; time may be flowing faster or more slowly, or perceptions may differ.

J. R. R. Tolkien used frame stories throughout his Middle-earth writings, especially his legendarium, to make the works resemble a genuine mythology written and edited by many hands over a long period of time. He described in detail how his fictional characters wrote their books and transmitted them to others, and showed how later in-universe editors annotated the material.

J. R. R. Tolkien was attracted to medieval literature, and made use of it in his writings, both in his poetry, which contained numerous pastiches of medieval verse, and in his Middle-earth novels where he embodied a wide range of medieval concepts.

Tolkien's Art: 'A Mythology for England' is a 1979 book of Tolkien scholarship by Jane Chance, writing then as Jane Chance Nitzsche. The book looks in turn at Tolkien's essays "On Fairy-Stories" and "Beowulf: The Monsters and the Critics"; The Hobbit; the fairy-stories "Leaf by Niggle" and "Smith of Wootton Major"; the minor works "Lay of Autrou and Itroun", "The Homecoming of Beorhtnoth", "Imram", and Farmer Giles of Ham; The Lord of the Rings; and very briefly in the concluding section, The Silmarillion. In 2001, a second edition extended all the chapters but still treated The Silmarillion, that Tolkien worked on throughout his life, as a sort of coda.

Scholars, including psychoanalysts, have commented that J. R. R. Tolkien's Middle-earth stories about both Bilbo Baggins, protagonist of The Hobbit, and Frodo Baggins, protagonist of The Lord of the Rings, constitute psychological journeys. Bilbo returns from his journey to help recover the Dwarves' treasure from Smaug the dragon's lair in the Lonely Mountain changed, but wiser and more experienced. Frodo returns from his journey to destroy the One Ring in the fires of Mount Doom scarred by multiple weapons, and is unable to settle back into the normal life of his home, the Shire.

In Tolkien's legendarium, ancestry provides a guide to character. The apparently genteel Hobbits of the Baggins family turn out to be worthy protagonists of The Hobbit and The Lord of the Rings. Bilbo Baggins is seen from his family tree to be both a Baggins and an adventurous Took. Similarly, Frodo Baggins has some relatively outlandish Brandybuck blood. Among the Elves of Middle-earth, as described in The Silmarillion, the highest are the peaceful Vanyar, whose ancestors conformed most closely to the divine will, migrating to Aman and seeing the light of the Two Trees of Valinor; the lowest are the mutable Teleri; and in between are the conflicted Noldor. Scholars have analysed the impact of ancestry on Elves such as the creative but headstrong Fëanor, who makes the Silmarils. Among Men, Aragorn, hero of The Lord of the Rings, is shown by his descent from Kings, Elves, and an immortal Maia to be of royal blood, destined to be the true King who will restore his people. Scholars have commented that in this way, Tolkien was presenting a view of character from Norse mythology, and an Anglo-Saxon view of kingship, though others have called his implied views racist.

J. R. R. Tolkien's best-known novels, The Hobbit and The Lord of the Rings, both have the structure of quests, with a hero setting out, facing dangers, achieving a goal, and returning home. Where The Hobbit is a children's story with the simple goal of treasure, The Lord of the Rings is a more complex narrative with multiple quests. Its main quest, to destroy the One Ring, has been described as a reversed quest – starting with a much-desired treasure, and getting rid of it. That quest, too, is balanced against a moral quest, to scour the Shire and return it to its original state.

J. R. R. Tolkien repeatedly dealt with the theme of death and immortality in Middle-earth. He stated that the "real theme" of The Lord of the Rings was "Death and Immortality". In Middle-earth, Men are mortal, while Elves are immortal. One of his stories, The Tale of Aragorn and Arwen, explores the willing choice of death through the love of an immortal Elf for a mortal Man. He several times revisited the Old Norse theme of the mountain tomb, containing treasure along with the dead and visited by fighting. He brought multiple leading evil characters in The Lord of the Rings to a fiery end, including Gollum, the Nazgûl, the Dark Lord Sauron, and the evil Wizard Saruman, while in The Hobbit, the dragon Smaug is killed. Their destruction contrasts with the heroic deaths of two leaders of the free peoples, Théoden of Rohan and Boromir of Gondor, reflecting the early Medieval ideal of Northern courage. Despite these pagan themes, the work contains hints of Christianity, such as of the resurrection of Christ, as when the Lord of the Nazgûl, thinking himself victorious, calls himself Death, only to be answered by the crowing of a cockerel. There are, too, hints that the Elvish land of Lothlórien represents an Earthly Paradise. Scholars have commented that Tolkien clearly moved during his career from being oriented towards pagan themes to a more Christian theology.

The philologist and fantasy author J. R. R. Tolkien made use of multiple literary devices in The Lord of the Rings, from its narrative structure, to character pairing and the deliberate cultivation of an impression of depth. The narrative structure in particular has been seen as a pair of quests, a sequence of tableaux, a complex edifice, multiple spirals, and a medieval-style interlacing. The first volume, The Fellowship of the Ring, on the other hand, has a single narrative thread, and repeated episodes of danger and recuperation in five "Homely Houses". His prose style, too, has been both criticised and defended.