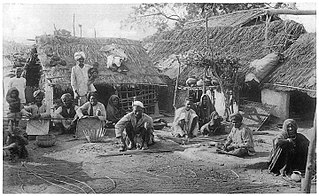

Caste is a form of social stratification characterised by endogamy, hereditary transmission of a style of life which often includes an occupation, ritual status in a hierarchy, and customary social interaction and exclusion based on cultural notions of purity and pollution. Its paradigmatic ethnographic example is the division of India's Hindu society into rigid social groups, with roots in India's ancient history and persisting to the present time. However, the economic significance of the caste system in India has been declining as a result of urbanisation and affirmative action programs. A subject of much scholarship by sociologists and anthropologists, the Hindu caste system is sometimes used as an analogical basis for the study of caste-like social divisions existing outside Hinduism and India. The term "caste" is also applied to morphological groupings in eusocial insects such as ants, bees, and termites.

Bhimrao Ramji Ambedkar was an Indian jurist, economist, social reformer and political leader who headed the committee drafting the Constitution of India from the Constituent Assembly debates, served as Law and Justice minister in the first cabinet of Jawaharlal Nehru, and inspired the Dalit Buddhist movement after renouncing Hinduism.

Jāti is the term traditionally used to describe a cohesive group of people in India, like a tribe, community, clan, sub-clan, or a religious sect. Each Jāti typically has an association with an occupation, geography or tribe. Different religious beliefs or linguistic groupings may also define some Jātis.

Endogamy is the practice of marrying within a specific social group, religious denomination, caste, or ethnic group, rejecting those from others as unsuitable for marriage or other close personal relationships.

The Belwar are a Hindu sanadhya Brahmin caste found in North India, and mostly in Uttar Pradesh. Sanadhya Brahmins are called Belwars in mainly Sitapur, Lakhimpur, Hardoi, Barabanki, Gonda and Lucknow. They are called as Bilwar or Bailwar. However they did like to be called Bilwar or Bailwaras it is a matter of pride for them .Some of the other caste think Belwar are of low class but it depends on their thinking

The caste system in India is the paradigmatic ethnographic example of caste. It has its origins in ancient India, and was transformed by various ruling elites in medieval, early-modern, and modern India, especially the Mughal Empire and the British Raj. It is today the basis of affirmative action programmes in India. The caste system consists of two different concepts, varna and jati, which may be regarded as different levels of analysis of this system.

Muslim communities in South Asia apply a system of religious stratification. It developed as a result of ethnic segregation between the foreign conquerors/ Upper caste Hindus who converted to Islam (Ashraf) and the local converts (Ajlaf) as well as the continuation of the Indian caste system among local converts. Non-Ashrafs are converts from Hinduism, usually from the lower castes. Pasmandas include Ajlaf and Arzal Muslims, and Ajlafs' statuses are defined by them being descendants of converts to Islam and are also defined by their pesha (profession).

Sir Herbert Hope Risley was a British ethnographer and colonial administrator, a member of the Indian Civil Service who conducted extensive studies on the tribes and castes of the Bengal Presidency. He is notable for the formal application of the caste system to the entire Hindu population of British India in the 1901 census, of which he was in charge. As an exponent of scientific racism, he used the ratio of the width of a nose to its height to divide Indians into Aryan and Dravidian races, as well as seven castes.

The Ghosi are a Muslim community found mainly in North India.

The Muslim Teli are members of the Teli caste who follow Sunni Islam. They are found in India and Pakistan.

The Momin Qassar are a South Asian community traditionally involved in [Chicken fabric]]. They are considered to be Muslim converts from the Hindu Shaikh caste, and are found in North India and Pakistan. The community is also known as Charhoa and Gazar in Pakistan and Momin Qassar in India. They also use surname as "Hawari".

The Khanzada or Khan Zadeh are a community of Muslim Rajputs found in the Awadh region of Uttar Pradesh, India. This community is distinct from the Rajasthani Khanzada Rajput, the descendants of Wali-e-Mewat Raja Naher Khan, who are a sub-clan of Jadaun gotra. They are also a community of Muslim Rajputs. They refer to themselves as Musalman Rajputs. After the Partition of India in 1947, many members of this community migrated to Pakistan.

The Thakurai are a Muslim Rajput community found in the state of Bihar in India. They are mostly concentrated around [East and West Champaran District ] the surrounding region. A small number are also found in the Terai region of Nepal.

The Sikligar is a community found in the states of Gujarat, Haryana, Rajasthan and Punjab in India. They are also known as the Moyal and Panchal. They are Hindu in Gujarat, Telangana, Andhra Pradesh and Sikh in Punjab, and both Hindu and Sikh in Haryana.

The Bharbhunja/ Bhurji/ Bhojwal/ bhujwa are a largely Hindu caste found in North India and Maharashtra. They are also known as Kalenra in Maharashtra, Mehra in Punjab and in Uttar Pradesh. A small number are also found in the Terai region of Nepal.

The Bandhmati are a Hindu caste found in the state of Uttar Pradesh in India. They are also known as Banbasi.

The Heri are a Hindu caste found in the states of Haryana and Punjab in India.

The Bias are a Brahmin community found in the Indian states of Haryana, Punjab, Gujarat, Rajasthan, Uttar Pradesh and Delhi. They trace their origin to Vyasa who wrote Mahabharata.

Robert Vane Russell was a British civil servant, known for his role as Superintendent of Ethnography for what was then the Central Provinces of British India, coordinating the production of publications detailing the peoples of the region. Russell served as Superintendent of Census Operations for the 1901 Census of India.

The People of India is a title that has been used for at least three books, all of which focussed primarily on ethnography.