Dentition pertains to the development of teeth and their arrangement in the mouth. In particular, it is the characteristic arrangement, kind, and number of teeth in a given species at a given age. That is, the number, type, and morpho-physiology of the teeth of an animal.

Forensic dentistry or forensic odontology involves the handling, examination, and evaluation of dental evidence in a criminal justice context. Forensic dentistry is used in both criminal and civil law. Forensic dentists assist investigative agencies in identifying human remains, particularly in cases when identifying information is otherwise scarce or nonexistent—for instance, identifying burn victims by consulting the victim's dental records. Forensic dentists may also be asked to assist in determining the age, race, occupation, previous dental history, and socioeconomic status of unidentified human beings.

Hyperdontia is the condition of having supernumerary teeth, or teeth that appear in addition to the regular number of teeth. They can appear in any area of the dental arch and can affect any dental organ. The opposite of hyperdontia is hypodontia, where there is a congenital lack of teeth, which is a condition seen more commonly than hyperdontia. The scientific definition of hyperdontia is "any tooth or odontogenic structure that is formed from tooth germ in excess of usual number for any given region of the dental arch." The additional teeth, which may be few or many, can occur on any place in the dental arch. Their arrangement may be symmetrical or non-symmetrical.

The premolars, also called premolar teeth, or bicuspids, are transitional teeth located between the canine and molar teeth. In humans, there are two premolars per quadrant in the permanent set of teeth, making eight premolars total in the mouth. They have at least two cusps. Premolars can be considered transitional teeth during chewing, or mastication. They have properties of both the canines, that lie anterior and molars that lie posterior, and so food can be transferred from the canines to the premolars and finally to the molars for grinding, instead of directly from the canines to the molars.

Hypodontia is defined as the developmental absence of one or more teeth excluding the third molars. It is one of the most common dental anomalies, and can have a negative impact on function, and also appearance. It rarely occurs in primary teeth and the most commonly affected are the adult second premolars and the upper lateral incisors. It usually occurs as part of a syndrome that involves other abnormalities and requires multidisciplinary treatment.

Black hair is the darkest and most common of all human hair colors globally, due to large populations with this trait. This hair type contains a much more dense quantity of eumelanin pigmentation in comparison to other hair colors, such as brown, blonde and red. In English, various types of black hair are sometimes described as soft-black, raven black, or jet-black. The range of skin colors associated with black hair is vast, ranging from the palest of light skin tones to dark skin. Black-haired humans can have dark or light eyes.

Shovel-shaped incisors are incisors whose lingual surfaces are scooped as a consequence of lingual marginal ridges, crown curvature, or basal tubercles, either alone or in combination.

Talon cusp is a rare dental anomaly resulting in an extra cusp or cusp-like projection on an anterior tooth, located on the inside surface of the affected tooth. Sometimes it can also be found on the facial surface of the anterior tooth.

Overjet is the extent of horizontal (anterior-posterior) overlap of the maxillary central incisors over the mandibular central incisors. In class II malocclusion the overjet is increased as the maxillary central incisors are protruded.

Ectodysplasin A receptor (EDAR) is a protein that in humans is encoded by the EDAR gene. EDAR is a cell surface receptor for ectodysplasin A which plays an important role in the development of ectodermal tissues such as the skin. It is structurally related to members of the TNF receptor superfamily.

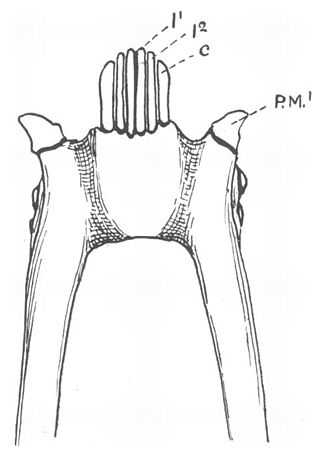

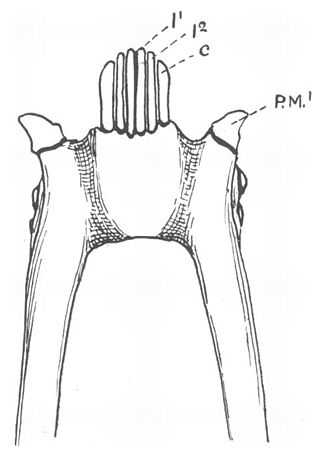

A toothcomb is a dental structure found in some mammals, comprising a group of front teeth arranged in a manner that facilitates grooming, similar to a hair comb. The toothcomb occurs in lemuriform primates, treeshrews, colugos, hyraxes, and some African antelopes. The structures evolved independently in different types of mammals through convergent evolution and varies both in dental composition and structure. In most mammals the comb is formed by a group of teeth with fine spaces between them. The toothcombs in most mammals include incisors only, while in lemuriform primates they include incisors and canine teeth that tilt forward at the front of the lower jaw, followed by a canine-shaped first premolar. The toothcombs of colugos and hyraxes take a different form with the individual incisors being serrated, providing multiple tines per tooth.

Enamel hypoplasia is a defect of the teeth in which the enamel is deficient in quantity, caused by defective enamel matrix formation during enamel development, as a result of inherited and acquired systemic condition(s). It can be identified as missing tooth structure and may manifest as pits or grooves in the crown of the affected teeth, and in extreme cases, some portions of the crown of the tooth may have no enamel, exposing the dentin. It may be generalized across the dentition or localized to a few teeth. Defects are categorized by shape or location. Common categories are pit-form, plane-form, linear-form, and localised enamel hypoplasia. Hypoplastic lesions are found in areas of the teeth where the enamel was being actively formed during a systemic or local disturbance. Since the formation of enamel extends over a long period of time, defects may be confined to one well-defined area of the affected teeth. Knowledge of chronological development of deciduous and permanent teeth makes it possible to determine the approximate time at which the developmental disturbance occurred. Enamel hypoplasia varies substantially among populations and can be used to infer health and behavioural impacts from the past. Defects have also been found in a variety of non-human animals.

A tooth is a hard, calcified structure found in the jaws of many vertebrates and used to break down food. Some animals, particularly carnivores and omnivores, also use teeth to help with capturing or wounding prey, tearing food, for defensive purposes, to intimidate other animals often including their own, or to carry prey or their young. The roots of teeth are covered by gums. Teeth are not made of bone, but rather of multiple tissues of varying density and hardness that originate from the outermost embryonic germ layer, the ectoderm.

Odontometrics is the measurement and study of tooth size. It is used in biological anthropology and bioarchaeology to study human phenotypic variation. The rationale for use is similar to that of the study of dentition, the structure and arrangement of teeth. There are a number of features that can be observed in human teeth through the use of odontometrics.

Teeth are common to most vertebrates, but mammalian teeth are distinctive in having a variety of shapes and functions. This feature first arose among early therapsids during the Permian, and has continued to the present day. All therapsid groups with the exception of the mammals are now extinct, but each of these groups possessed different tooth patterns, which aids with the classification of fossils.

Maxillary lateral incisor agenesis (MLIA) is lack of development (agenesis) of one or both of the maxillary lateral incisor teeth. In normal human dentition, this would be the second tooth on either side from the center of the top row of teeth. The condition is bilateral if the incisor is absent on both sides or unilateral if only one is missing. It appears to have a genetic component.

Changes to the dental morphology and jaw are major elements of hominid evolution. These changes were driven by the types and processing of food eaten. The evolution of the jaw is thought to have facilitated encephalization, speech, and the formation of the uniquely human chin.

The ASUDAS is a reference system for collecting data on human tooth morphology and variation created by Christy G. Turner II, Christian R. Nichol, and G. Richard Scott. The ASUDAS gives detailed descriptions for common crown and root shape variants and their different degrees of expression. It also comprises a set of reference plaques illustrating dental variants as well as showing their expression levels in 3D. The ASUDAS was designed to ensure a standardized scoring procedure with minimum error in order to warrant comparability between data collected by different observers.

Near Eastern bioarchaeology covers the study of human skeletal remains from archaeological sites in Cyprus, Egypt, Levantine coast, Jordan, Turkey, Iran, Saudi Arabia, Qatar, Kuwait, Bahrain, United Arab Emirates, Oman, and Yemen.

The analysis of dental remains is a valuable tool to archaeologists. Teeth are hard, highly mineralised and chemically stable, so therefore preserve well and are one of the most commonly found animals remains. Analysis of these remains also yields a wealth of information. It can not only be used to determine the sex and age of the individual whose mandibular or dental remains have been found, but can also shed light on their diet, pathology, and even their geographic origins through isotope analysis.