Vespertilionidae is a family of microbats, of the order Chiroptera, flying, insect-eating mammals variously described as the common, vesper, or simple nosed bats. The vespertilionid family is the most diverse and widely distributed of bat families, specialised in many forms to occupy a range of habitats and ecological circumstances, and it is frequently observed or the subject of research. The facial features of the species are often simple, as they mainly rely on vocally emitted echolocation. The tails of the species are enclosed by the lower flight membranes between the legs. Over 300 species are distributed all over the world, on every continent except Antarctica. It owes its name to the genus Vespertilio, which takes its name from a word for bat, vespertilio, derived from the Latin term vesper meaning 'evening'; they are termed "evening bats" and were once referred to as "evening birds".

Pipistrellus is a genus of bats in the family Vespertilionidae and subfamily Vespertilioninae. The name of the genus is derived from the Italian word pipistrello, meaning "bat".

The tricolored bat or American perimyotis is a species of microbat native to eastern North America. Formerly known as the eastern pipistrelle, based on the incorrect belief that it was closely related to European Pipistrellus species, the closest known relative of the tricolored bat is now recognized as the canyon bat. Its common name "tricolored bat" derives from the coloration of the hairs on its back, which have three distinct color bands. It is the smallest bat species in the eastern and midwestern US, with individuals weighing only 4.6–7.9 g (0.16–0.28 oz). This species mates in the fall before hibernation, though due to sperm storage, females do not become pregnant until the spring. Young are born helpless, though rapidly develop, flying and foraging for themselves by four weeks old. It has a relatively long lifespan, and can live nearly fifteen years.

The common pipistrelle is a small pipistrelle microbat whose very large range extends across most of Europe, North Africa, South Asia, and may extend into Korea. It is one of the most common bat species in the British Isles. In Europe, the northernmost confirmed records are from southern Finland near 60°N.

The soprano pipistrelle is a small species of bat. It is found in Europe and often roosts on buildings.

Savi's pipistrelle is a species of vesper bat found across North West Africa, the Mediterranean region and the Middle East. It feeds at night on flying insects. In the summer it roosts under bark, in holes in trees, in old buildings and in rock crevices but in winter it prefers roosts where the temperature is more even such as caves, underground vaults and deep rock cracks.

Nathusius' pipistrelle is a small bat in the genus Pipistrellus. It is very similar to the common pipistrelle and has been overlooked in many areas until recently but it is widely distributed across Europe. It was described by two German naturalists, Alexander Keyserling and Johann Heinrich Blasius, and named by them after Hermann von Nathusius, in gratitude for his support of their research.

The angulate pipistrelle, also known as the New Guinea pipistrelle, is a species of vesper bat found in Papua New Guinea and the Solomon Islands.

Endo's pipistrelle is a species of vesper bat that is endemic to Japan. It is found in temperate forests.

The little pied bat is a species of vesper bat in the family Vespertilionidae. It is found only in semi-arid woodlands in eastern Australia.

The western false pipistrelle, species Falsistrellus mackenziei, is a vespertilionid bat that occurs in Southwest Australia. The population is declining due to loss of its habitat, old growth in tall eucalypt forest which has largely been clear felled for tree plantations, wheat cultivation and urbanisation. Although it is one of the largest Australian bats of the family, the species was not recorded or described until the early 1960s. A darkly colored bat with reddish brown fur and prominent ears, they fly rapidly around the upper canopy of trees in pursuit of flying insects.

The southern forest bat is a vesper bat found in Australia.

The little forest bat is a species of vesper bat in the family Vespertilionidae. It is found only in south-eastern Australia, including Tasmania. It is a tiny bat often weighing less than 4 g (0.14 oz). It is sometimes referred to as Australia's smallest mammal, although the Northern or Koopmans Pipistrelle, Pipistrellus westralis, is possibly smaller, weighing on average around 3 g (0.11 oz). It is the smallest bat in Tasmania

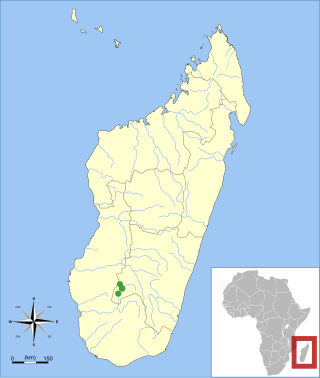

Pipistrellus raceyi, also known as Racey's pipistrelle, is a bat from Madagascar, in the genus Pipistrellus. Although unidentified species of Pipistrellus had been previously reported from Madagascar since the 1990s, P. raceyi was not formally named until 2006. It is apparently most closely related to the Asian species P. endoi, P. paterculus, and P. abramus, and its ancestors probably reached Madagascar from Asia. P. raceyi has been recorded at four sites, two in the eastern and two in the western lowlands. In the east, it is found in open areas and has been found roosting in a building; in the west it occurs in dry forest. Because of uncertainties about its ecology, it is listed as "Data Deficient" on the IUCN Red List.

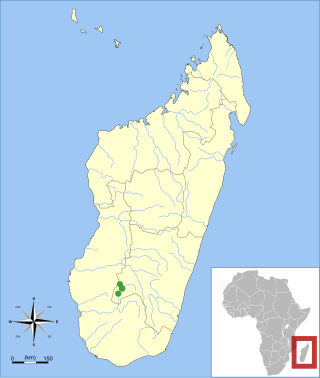

The Isalo serotine is a vesper bat of Madagascar in the genus Laephotis. It is known only from the vicinity of the Isalo National Park in the southwestern part of the island, where it has been caught in riverine habitats. After the first specimen was caught in 1967, it was described as a subspecies of Eptesicus somalicus in 1995. After four more specimens were collected in 2002 and 2003, it was recognized as a separate species. Because of its small distribution and the threat of habitat destruction, it is considered "vulnerable" in the IUCN Red List.

The cinnamon red bat is a species of bat in the family Vespertilionidae. It was first described from a specimen that had been collected in Chile. For more than one hundred years after its initial description, it was largely considered a synonym of the eastern red bat. From the 1980s onward, it was frequently recognized as distinct from the eastern red bat due to its fur coloration and differences in range. It has deep red fur, lacking white "frosting" on the tips of individual hairs seen in other members of Lasiurus. It has a forearm length of 39–42 mm (1.5–1.7 in) and a weight of 9.5–11.0 g (0.34–0.39 oz).

The long-fingered bat is a carnivorous species of vesper bat. It is native to coastal areas around the Mediterranean Sea, as well as a few patches of land in western Iran. Due to the fact that its population is in decline, it has been listed as Vulnerable on the IUCN Red List since 1988.

Lindy Lumsden is a principal research scientist with the Department of Environment, Land, Water and Planning, at the Arthur Rylah Institute for Environmental Research, in Melbourne, Australia.

The Alashanian pipistrelle is a species of bat in the family Vespertilionidae. It is found in China, South Korea, Mongolia, Japan, and Russia.

Pipistrellini is a tribe of bats in the family Vespertilionidae. It contains several genera found throughout the Old World and Australasia, including the pipistrelles, noctules and related species.