Biotite is a common group of phyllosilicate minerals within the mica group, with the approximate chemical formula K(Mg,Fe)3AlSi3O10(F,OH)2. It is primarily a solid-solution series between the iron-endmember annite, and the magnesium-endmember phlogopite; more aluminous end-members include siderophyllite and eastonite. Biotite was regarded as a mineral species by the International Mineralogical Association until 1998, when its status was changed to a mineral group. The term biotite is still used to describe unanalysed dark micas in the field. Biotite was named by J.F.L. Hausmann in 1847 in honor of the French physicist Jean-Baptiste Biot, who performed early research into the many optical properties of mica.

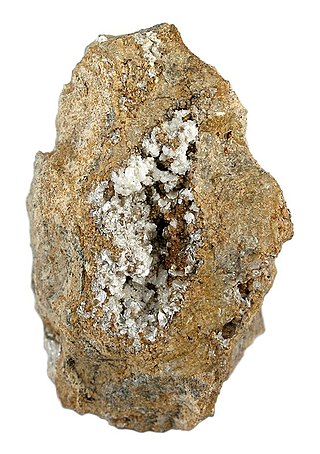

Kaolinite ( KAY-ə-lə-nyte, -lih-; also called kaolin) is a clay mineral, with the chemical composition Al2Si2O5(OH)4. It is a layered silicate mineral, with one tetrahedral sheet of silica (SiO4) linked through oxygen atoms to one octahedral sheet of alumina (AlO6).

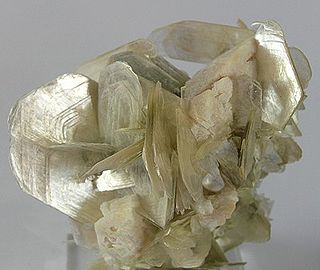

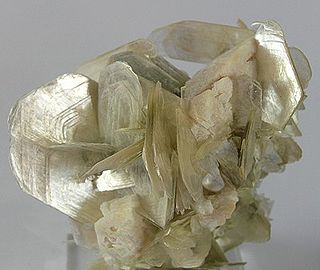

Muscovite (also known as common mica, isinglass, or potash mica) is a hydrated phyllosilicate mineral of aluminium and potassium with formula KAl2(AlSi3O10)(F,OH)2, or (KF)2(Al2O3)3(SiO2)6(H2O). It has a highly perfect basal cleavage yielding remarkably thin laminae (sheets) which are often highly elastic. Sheets of muscovite 5 meters × 3 meters (16.5 feet × 10 feet) have been found in Nellore, India.

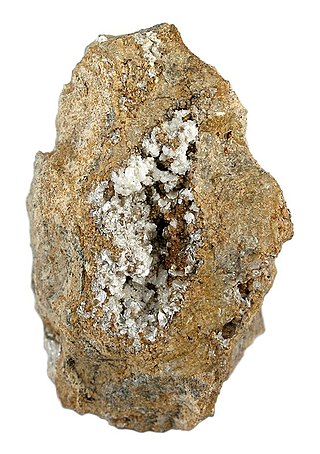

Clay is a type of fine-grained natural soil material containing clay minerals (hydrous aluminium phyllosilicates, e.g. kaolinite, Al2Si2O5(OH)4). Most pure clay minerals are white or light-coloured, but natural clays show a variety of colours from impurities, such as a reddish or brownish colour from small amounts of iron oxide.

Gibbsite, Al(OH)3, is one of the mineral forms of aluminium hydroxide. It is often designated as γ-Al(OH)3 (but sometimes as α-Al(OH)3). It is also sometimes called hydrargillite (or hydrargyllite).

Bentonite is an absorbent swelling clay consisting mostly of montmorillonite which can either be Na-montmorillonite or Ca-montmorillonite. Na-montmorillonite has a considerably greater swelling capacity than Ca-montmorillonite.

Dickite is a phyllosilicate clay mineral named after the metallurgical chemist Allan Brugh Dick, who first described it. It is chemically composed of 20.90% aluminium, 21.76% silicon, 1.56% hydrogen and 55.78% oxygen. It has the same composition as kaolinite, nacrite, and halloysite, but with a different crystal structure (polymorph). Dickite sometimes contains impurities such as titanium, iron, magnesium, calcium, sodium and potassium.

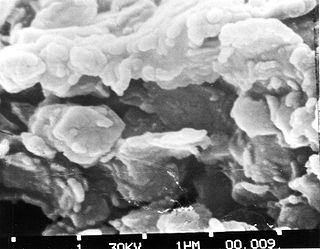

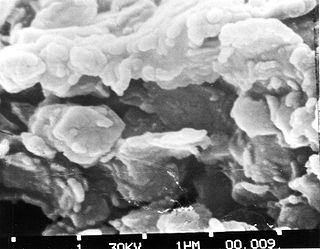

Montmorillonite is a very soft phyllosilicate group of minerals that form when they precipitate from water solution as microscopic crystals, known as clay. It is named after Montmorillon in France. Montmorillonite, a member of the smectite group, is a 2:1 clay, meaning that it has two tetrahedral sheets of silica sandwiching a central octahedral sheet of alumina. The particles are plate-shaped with an average diameter around 1 μm and a thickness of 0.96 nm; magnification of about 25,000 times, using an electron microscope, is required to resolve individual clay particles. Members of this group include saponite, nontronite, beidellite, and hectorite.

Illite, also called hydromica or hydromuscovite, is a group of closely related non-expanding clay minerals. Illite is a secondary mineral precipitate, and an example of a phyllosilicate, or layered alumino-silicate. Its structure is a 2:1 sandwich of silica tetrahedron (T) – alumina octahedron (O) – silica tetrahedron (T) layers. The space between this T-O-T sequence of layers is occupied by poorly hydrated potassium cations which are responsible for the absence of swelling. Structurally, illite is quite similar to muscovite with slightly more silicon, magnesium, iron, and water and slightly less tetrahedral aluminium and interlayer potassium. The chemical formula is given as (K,H3O)(Al,Mg,Fe)2(Si,Al)4O10[(OH)2·(H2O)], but there is considerable ion (isomorphic) substitution. It occurs as aggregates of small monoclinic grey to white crystals. Due to the small size, positive identification usually requires x-ray diffraction or SEM-EDS analysis. Illite occurs as an altered product of muscovite and feldspar in weathering and hydrothermal environments; it may be a component of sericite. It is common in sediments, soils, and argillaceous sedimentary rocks as well as in some low grade metamorphic rocks. The iron-rich member of the illite group, glauconite, in sediments can be differentiated by x-ray analysis.

A smectite is a mineral mixture of various swelling sheet silicates (phyllosilicates), which have a three-layer 2:1 (TOT) structure and belong to the clay minerals. Smectites mainly consist of montmorillonite, but can often contain secondary minerals such as quartz and calcite.

Expansive clay is a clay soil that is prone to large volume changes that are directly related to changes in water content. Soils with a high content of expansive minerals can form deep cracks in drier seasons or years; such soils are called vertisols. Soils with smectite clay minerals, including montmorillonite and bentonite, have the most dramatic shrink–swell capacity.

Metakaolin is the anhydrous calcined form of the clay mineral kaolinite. Rocks that are rich in kaolinite are known as china clay or kaolin, traditionally used in the manufacture of porcelain. The particle size of metakaolin is smaller than cement particles, but not as fine as silica fume.

Nontronite is the iron(III) rich member of the smectite group of clay minerals. Nontronites typically have a chemical composition consisting of more than ~30% Fe2O3 and less than ~12% Al2O3 (ignited basis). Nontronite has very few economic deposits like montmorillonite. Like montmorillonite, nontronite can have variable amounts of adsorbed water associated with the interlayer surfaces and the exchange cations.

Brammallite is a sodium rich analogue of illite. First described in 1943 for an occurrence in Llandybie, Carmarthenshire, Wales, it was named for British geologist and mineralogist Alfred Brammall (1879–1954).

Iberulites are a particular type of microspherulites that develop in the atmosphere (troposphere), finally falling to the Earth's surface. The name comes from the Iberian Peninsula where they were discovered.

Chamosite is the Fe2+end member of the chlorite group. A hydrous aluminium silicate of iron, which is produced in an environment of low to moderate grade of metamorphosed iron deposits, as gray or black crystals in oolitic iron ore. Like other chlorites, it is a product of the hydrothermal alteration of pyroxenes, amphiboles and biotite in igneous rock. The composition of chlorite is often related to that of the original igneous mineral so that more Fe-rich chlorites are commonly found as replacements of the Fe-rich ferromagnesian minerals (Deer et al., 1992).

Pimelite was discredited as a mineral species by the International Mineralogical Association (IMA) in 2006, in an article which suggests that "pimelite" specimens are probably willemseite, or kerolite. This was a mass discreditation, and not based on any re-examination of the type material. Nevertheless, a considerable number of papers have been written, verifying that pimelite is a nickel-dominant smectite. It is always possible to redefine a mineral wrongly discredited.

The soil matrix is the solid phase of soils, and comprise the solid particles that make up soils. Soil particles can be classified by their chemical composition (mineralogy) as well as their size. The particle size distribution of a soil, its texture, determines many of the properties of that soil, in particular hydraulic conductivity and water potential, but the mineralogy of those particles can strongly modify those properties. The mineralogy of the finest soil particles, clay, is especially important.

Antigorite is a lamellated, monoclinic mineral in the phyllosilicate serpentine subgroup with the ideal chemical formula of (Mg,Fe2+)3Si2O5(OH)4. It is the high-pressure polymorph of serpentine and is commonly found in metamorphosed serpentinites. Antigorite, and its serpentine polymorphs, play an important role in subduction zone dynamics due to their relative weakness and high weight percent of water (up to 13 weight % H2O). It is named after its type locality, the Geisspfad serpentinite, Valle Antigorio in the border region of Italy/Switzerland and is commonly used as a gemstone in jewelry and carvings.