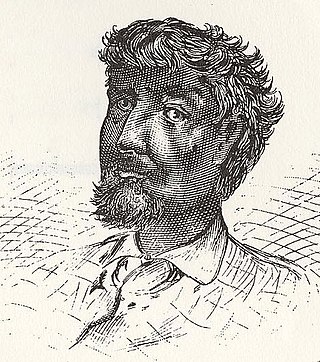

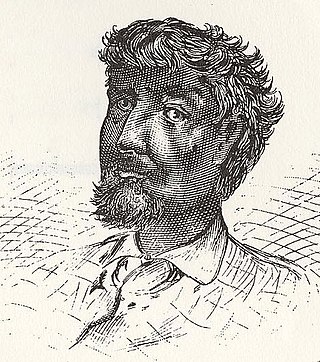

Jean Baptiste Point du Sable is regarded as the first permanent non-native settler of what would later become Chicago, Illinois, and is recognized as the "Founder of Chicago". A school, museum, harbor, park, bridge, and road have been named in his honor. The site where he settled near the mouth of the Chicago River around the 1780s is recognized as a National Historic Landmark, now located in Pioneer Court.

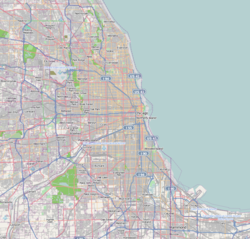

Hyde Park is the 41st of the 77 community areas of Chicago. It is located on the South Side, near the shore of Lake Michigan 7 miles (11 km) south of the Loop.

Washington Park is a community area on the South Side of Chicago which includes the 372 acre (1.5 km2) park of the same name, stretching east-west from Cottage Grove Avenue to the Dan Ryan Expressway, and north-south from 51st Street to 63rd. It is home to the DuSable Museum of African American History. The park was the proposed site of the Olympic Stadium and the Olympic Aquatics Center in Chicago's bid to host the 2016 Summer Olympics.

Douglas, on the South Side of Chicago, Illinois, is one of Chicago's 77 community areas. The neighborhood is named for Stephen A. Douglas, Illinois politician and Abraham Lincoln's political foe, whose estate included a tract of land given to the federal government. This tract later was developed for use as the Civil War Union training and prison camp, Camp Douglas, located in what is now the eastern portion of the Douglas neighborhood. Douglas gave that part of his estate at Cottage Grove and 35th to the Old University of Chicago. The Chicago 2016 Olympic bid planned for the Olympic Village to be constructed on a 37-acre (15 ha) truck parking lot, south of McCormick Place, that is mostly in the Douglas community area and partly in the Near South Side.

Jean Baptiste Point DuSable High School is a public high school in the Bronzeville neighborhood on the South Side of Chicago, Illinois, United States, owned by Chicago Public Schools and named after Chicago's first permanent non-native settler, Jean Baptiste Point Du Sable. Built between 1931 and 1934, it opened in 1935.

The DuSable Bridge is a bascule bridge that carries Michigan Avenue across the main stem of the Chicago River in downtown Chicago, Illinois, United States. The bridge was proposed in the early 20th century as part of a plan to link Grant Park (downtown) and Lincoln Park (uptown) with a grand boulevard. Construction of the bridge started in 1918, it opened to traffic in 1920, and decorative work was completed in 1928. The bridge provides passage for vehicles and pedestrians on two levels. An example of a fixed trunnion bascule bridge, it may be raised to allow tall ships and boats to pass underneath. The bridge is included in the Michigan–Wacker Historic District and has been designated as a Chicago Landmark.

Washington Park is a 372-acre (1.5 km2) park between Cottage Grove Avenue and Martin Luther King Drive, located at 5531 S. Martin Luther King Dr. in the Washington Park community area on the South Side of Chicago. It was named for President George Washington in 1880. Washington Park is the largest of four Chicago Park District parks named after persons surnamed Washington. Located in the park is the DuSable Museum of African American History. This park was the proposed site of the Olympic Stadium and the Olympic swimming venue for Chicago's bid to host the 2016 Summer Olympics. Washington Park was added to the National Register of Historic Places on August 20, 2004.

Margaret Taylor-Burroughs, also known as Margaret Taylor Goss, Margaret Taylor Goss Burroughs or Margaret T G Burroughs, was an American visual artist, writer, poet, educator, and arts organizer. She co-founded the Ebony Museum of Chicago, now the DuSable Museum of African American History. An active member of the African-American community, she also helped to establish the South Side Community Art Center, whose opening on May 1, 1941 was dedicated by the first lady of the United States Eleanor Roosevelt. There, at the age of 23, Burroughs served as the youngest member of its board of directors. A long-time educator, she spent most of her career at DuSable High School. Taylor-Burroughs was a prolific writer, with her efforts directed toward the exploration of the Black experience and toward children, especially to their appreciation of their cultural identity and to their introduction and growing awareness of art. She is also credited with the founding of Chicago's Lake Meadows Art Fair in the early 1950s.

Debra Hand is a self-taught artist and sculptor from Chicago, Illinois.

The Elam House, originally Simon Marks House, is a chateauesque-style residential building at 4726 South Martin Luther King Jr. Drive in Chicago, Illinois, United States. The house was designed by Henry L. Newhouse and built in 1903. It was later purchased by Melissia Ann Elam. It was designated a Chicago Landmark on March 21, 1979.

The South Side is one of the three major sections of the city of Chicago, Illinois. Geographically, it is the largest of the three sections of the city, with the other two being the North Side and the West Side. It radiates and lies south of the city's downtown area, the Chicago Loop.

Hank Willis Thomas is an American conceptual artist. Based in Brooklyn, New York, he works primarily with themes related to identity, history, and popular culture.

Thomas Miller was a prolific graphic designer and visual artist, whose best known publicly accessible work is the collection of mosaics of the founders of DuSable Museum of African American History in Chicago, Illinois. The mosaics are a prominent feature of the lobby of the museum, the original portion of which was designed c.1915 by D.H. Burnham and Company to serve as the South Park Administration Building in Washington Park on the city's south side. After serving various purposes, the building became the home of the DuSable in 1973.

Gerald Williams is an American visual artist whose work has been influential within the Black Arts Movement, a transnational aesthetic phenomenon that first manifested in the 1960s and continues to evolve today. Williams was a founding member of AfriCOBRA. His work has been featured in exhibitions at some of the most important museums in the world, including the Tate Modern, the Museum of Contemporary Art, Chicago, the Studio Museum in Harlem, and the Institute of Contemporary Art, Philadelphia. In addition to his influence as a contemporary artist, he has served in the Peace Corps, taught in the public schools systems of Chicago and Washington, D.C., and served as an Arts and Crafts Center Director for the United States Air Force. In 2015, he moved back to his childhood neighborhood of Woodlawn, Chicago, where he currently lives and works. In 2019, Mr. Williams was awarded The Honorary Doctors of Philosophy in Art by the School of the Art Institute of Chicago, along with his co-founders of the AFRICOBRA, Jae Jarrell, and Wadsworth A. Jarrell.

Eva Maria Lewis is an American activist. From South Side, Chicago, she has led a number of local protests, including the July 11, 2016 youth march on Millennium Park to protest police brutality. She has also founded two organizations, The I Project and Youth for Black Lives.

William Thacker McBride Jr. was an African-American artist, designer and collector. McBride began his career in the 1930s in the circles of black art collectives and artistic opportunities afforded by the Works Progress Administration. He would ultimately leave his mark in Chicago as a driving force behind the South Side Community Art Center. McBride distinguished himself as a teacher, as a cultural and political activist, and as a collector of African art and artwork by black artists of his generation.

Geraldine McCullough (1917–2008) was an African American painter, sculptor and art professor. She was best known for her mostly abstract large-scale metal sculpture.