Related Research Articles

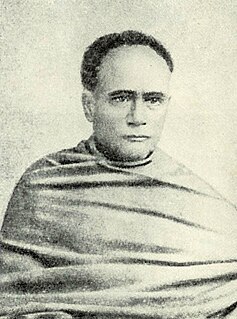

Raja Ram Mohan Roy was one of the founders of the Brahmo Sabha, the precursor of the Brahmo Samaj, a social-religious reform movement in the Indian subcontinent. He was given the title of Raja by Akbar II, the Mughal emperor. His influence was apparent in the fields of politics, public administration, education and religion. He was known for his efforts to abolish the practices of sati and child marriage. Raja Ram Mohan Roy is considered to be the "Father of the Indian Renaissance" by many historians.

Sir Charles Wilkins, KH, FRS, was an English typographer and Orientalist, and founding member of The Asiatic Society. He is notable as the first translator of Bhagavad Gita into English, and as the creator of the first Bengali typeface. In 1788, Wilkins was elected a member of the Royal Society.

William Carey was a British Christian missionary, Particular Baptist minister, translator, social reformer and cultural anthropologist who founded the Serampore College and the Serampore University, the first degree-awarding university in India.

Nathaniel Brassey Halhed was an English Orientalist and philologist.

Hicky's Bengal Gazette or the Original Calcutta General Advertiser was an English language weekly newspaper published in Kolkata, the capital of British India. It was the first newspaper printed in Asia, and was published for two years, between 1780 and 1782, before the East India Company seized the newspaper's types and printing press. Founded by James Augustus Hicky, a highly eccentric Irishman who had previously spent two years in jail for debt, the newspaper was a strong critic of the administration of Governor General Warren Hastings. The newspaper was important for its provocative journalism and its fight for free expression in India.

The Bengal Presidency, officially the Presidency of Fort William and later Bengal Province, was a subdivision of the British Empire in India. At the height of its territorial jurisdiction, it covered large parts of what is now South Asia and Southeast Asia. Bengal proper covered the ethno-linguistic region of Bengal. Calcutta, the city which grew around Fort William, was the capital of the Bengal Presidency. For many years, the Governor of Bengal was concurrently the Viceroy of India and Calcutta was the de facto capital of India until the early 20th-century.

Ishwar Chandra Vidyasagar CIE, born Ishwar Chandra Bandyopadhyay, was an Indian educator and social reformer. His efforts to simplify and modernise Bengali prose were significant. He also rationalised and simplified the Bengali alphabet and type, which had remained unchanged since Charles Wilkins and Panchanan Karmakar had cut the first (wooden) Bengali type in 1780. He is considered the "father of Bengali prose".

Fort William College was an academy of oriental studies and a centre of learning, founded on 10 July 1800 by Lord Wellesley, then Governor-General of British India, located within the Fort William complex in Calcutta. Wellesley backdated the statute of foundation to 4 May 1800, to commemorate the first anniversary of his victory over Tipu Sultan at Seringapatam. Thousands of books were translated from Sanskrit, Arabic, Persian, Bengali, Hindi, and Urdu into English at this institution. This college also promoted the printing and publishing of Urdu books.

Ganga Kishore Bhattacharya was an Indian editor and printer, and pioneer of Bengali print and journalism. He was born in Bahar village, near Serampore, Bengal. He started his career as a compositor at the Serampore Mission Press, later moving to Calcutta, where he first worked at the Ferris and Company Press before setting up his own, the Bengali Printing Press, along with his business partner, Harishchandra Ray.

James Atkinson was a surgeon, artist and Persian scholar - "a Renaissance man among Anglo-Indians"

In British India, the Vernacular Press Act (1878) was enacted to curtail the freedom of the Indian press and prevent the expression of criticism toward British policies—notably, the opposition that had grown with the outset of the Second Anglo-Afghan War (1878–80). The Act was proposed by Lord Lytton, then Viceroy of India, and was unanimously passed by the Viceroy's Council on 14 March 1878. The act excluded English-language publications as it was meant to control seditious writing in 'publications in Oriental languages' everywhere in the country, except for the South. Thus the British totally discriminated against the Indian Press.

The Calcutta School-Book Society was an organisation based in Kolkata during the British Raj. It was established in 1817, with the aim of publishing text books and supplying them to schools and madrasas in India.

The Serampur Mission Press was a book and newspaper publisher that operated in Serampur, Danish India, from 1800 to 1837.

The introduction and early development of printing in South India is attributed to missionary propaganda and the endeavours of the British East India Company. Among the pioneers in this arena, maximum attention is claimed by the Jesuit missionaries, followed by the Protestant Fathers and Hindu Pandits. Once the immigrants realized the importance of the local language, they began to disseminate their religious teachings through that medium, in effect ushering in the vernacular print culture in India. The first Tamil booklet was printed in 1554 in Lisbon - Cartilha em lingoa Tamul e Portugues in Romanized Tamil script by Vincente de Nazareth, Jorge Carvalho and Thoma da Cruz, all from the Paravar community of Tuticorin. it is also the first non-European language to find space in the modern printing culture in the world.

James Augustus Hicky was an Irishman who launched the first printed newspaper in India, Hicky's Bengal Gazette.

The Bengali-Assamese script is a modern eastern script that emerged from the Brahmic script. The name "Eastern Nagari script" is used more in academic discourses, while the name "Bengali script" dominates in public spheres.

John Zachariah Kiernander (1711–1799), also known as Johann Zacharias Kiernander, was a Swedish Lutheran missionary in India.

The Calcutta Chronicle and General Advertiser was a weekly English-language newspaper published in Kolkata, the capital of British India. It was one of the earliest newspapers in colonial India and was published for four years until it stopped its publication under pressure from the East India Company. Two Englishmen, Daniel Stuart and Joseph Cooper, founded the newspaper and also set up the Chronicle Printing Press. A large portion of the newspaper was dedicated to advertisements, and therefore was also called the 'General Advertiser'.

The India Gazette; or, Calcutta Public Advertiser was an English language weekly newspaper published in Kolkata, the capital of British India. It was the second newspaper printed in India. Founded by Bernard Messink and Peter Reed, two East India Company employees, the paper was a strong supporter of the administration of the Governor General Warren Hastings, and a rival to India's first newspaper Hicky's Bengal Gazette. It was founded on 18 November 1780

Freedom of the press in British India or freedom of the press in pre-independence India refers to the censorship on print media during the period of British rule by the British Crown on the Indian subcontinent from 1858 to 1947. The British Indian press was legally protected by the set of laws such as Vernacular Press Act, Censorship of Press Act, 1799, Metcalfe Act and Indian Press Act, 1910, while the media outlets were regulated by the Licensing Regulations, 1823, Licensing Act, 1857 and Registration Act, 1867. The British administrators in the India subcontinent brought a set of rules and regulations into effect designed to prevent circulating claimed inaccurate, media bias and disinformation across the subcontinent.

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 Graham Shaw, Printing in Calcutta to 1800, (London:The Bibliographical Society, 1981).

- ↑ Miles Ogborn, Indian Ink: script and print in the making of the English East India Company, (Chicago: University of Chicago, 2007).

- ↑ S. Natarajan: A history of the Press in India, (New York: Asia Publishing House, 1962).

- ↑ Shaw (1981) cites pp. 707 and 852 of G. Cannon ed, The Letters of William Jones (London: Vol 2.)

- ↑ Chris Bayly, Empire and Information: Intelligence Gathering and Social Communication in India, 1780-1870 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1996).

- ↑ Roebuck, T. (1819) The Annals of the College of Fort William.