Hepatitis C is an infectious disease caused by the hepatitis C virus (HCV) that primarily affects the liver; it is a type of viral hepatitis. During the initial infection period, people often have mild or no symptoms. Early symptoms can include fever, dark urine, abdominal pain, and yellow tinged skin. The virus persists in the liver, becoming chronic, in about 70% of those initially infected. Early on, chronic infection typically has no symptoms. Over many years however, it often leads to liver disease and occasionally cirrhosis. In some cases, those with cirrhosis will develop serious complications such as liver failure, liver cancer, or dilated blood vessels in the esophagus and stomach.

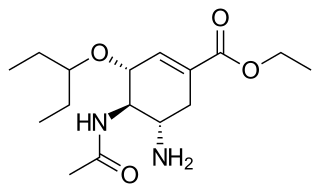

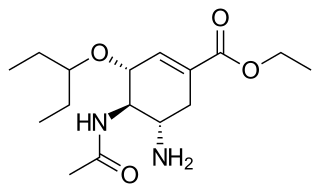

Oseltamivir, sold under the brand name Tamiflu, is an antiviral medication used to treat and prevent influenza A and influenza B, viruses that cause the flu. Many medical organizations recommend it in people who have complications or are at high risk of complications within 48 hours of first symptoms of infection. They recommend it to prevent infection in those at high risk, but not the general population. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) recommends that clinicians use their discretion to treat those at lower risk who present within 48 hours of first symptoms of infection. It is taken by mouth, either as a pill or liquid.

Feline infectious peritonitis (FIP) is the name given to a common and aberrant immune response in cats to infection with feline coronavirus (FCoV).

Genital herpes is a herpes infection of the genitals caused by the herpes simplex virus (HSV). Most people either have no or mild symptoms and thus do not know they are infected. When symptoms do occur, they typically include small blisters that break open to form painful ulcers. Flu-like symptoms, such as fever, aching, or swollen lymph nodes, may also occur. Onset is typically around 4 days after exposure with symptoms lasting up to 4 weeks. Once infected further outbreaks may occur but are generally milder.

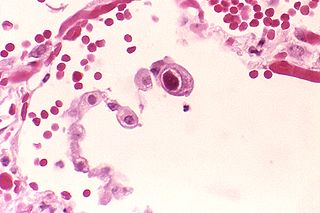

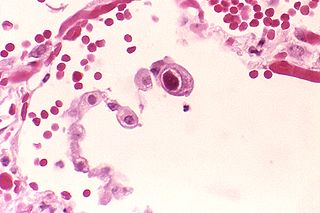

Human betaherpesvirus 5, also called human cytomegalovirus (HCMV), is species of virus in the genus Cytomegalovirus, which in turn is a member of the viral family known as Herpesviridae or herpesviruses. It is also commonly called CMV. Within Herpesviridae, HCMV belongs to the Betaherpesvirinae subfamily, which also includes cytomegaloviruses from other mammals. CMV is a double-stranded DNA virus.

Herpes simplex, often known simply as herpes, is a viral infection caused by the herpes simplex virus. Herpes infections are categorized by the area of the body that is infected. The two major types of herpes are oral herpes and genital herpes, though other forms also exist.

A neutralizing antibody (NAb) is an antibody that defends a cell from a pathogen or infectious particle by neutralizing any effect it has biologically. Neutralization renders the particle no longer infectious or pathogenic. Neutralizing antibodies are part of the humoral response of the adaptive immune system against viruses, intracellular bacteria and microbial toxin. By binding specifically to surface structures (antigen) on an infectious particle, neutralizing antibodies prevent the particle from interacting with its host cells it might infect and destroy.

Ebola, also known as Ebola virus disease (EVD) and Ebola hemorrhagic fever (EHF), is a viral hemorrhagic fever in humans and other primates, caused by ebolaviruses. Symptoms typically start anywhere between two days and three weeks after infection. The first symptoms are usually fever, sore throat, muscle pain, and headaches. These are usually followed by vomiting, diarrhoea, rash and decreased liver and kidney function, at which point some people begin to bleed both internally and externally. It kills between 25% and 90% of those infected – about 50% on average. Death is often due to shock from fluid loss, and typically occurs between six and 16 days after the first symptoms appear. Early treatment of symptoms increases the survival rate considerably compared to late start. An Ebola vaccine was approved by the US FDA in December 2019.

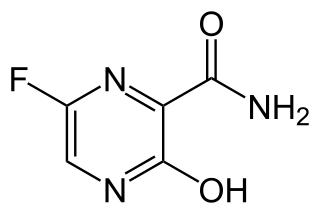

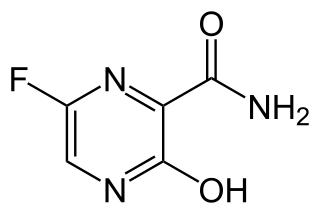

Favipiravir, sold under the brand name Avigan among others, is an antiviral medication used to treat influenza in Japan. It is also being studied to treat a number of other viral infections, including SARS-CoV-2. Like the experimental antiviral drugs T-1105 and T-1106, it is a pyrazinecarboxamide derivative.

Brincidofovir, sold under the brand name Tembexa, is an antiviral drug used to treat smallpox. Brincidofovir is a prodrug of cidofovir. Conjugated to a lipid, the compound is designed to release cidofovir intracellularly, allowing for higher intracellular and lower plasma concentrations of cidofovir, effectively increasing its activity against dsDNA viruses, as well as oral bioavailability.

ZMapp is an experimental biopharmaceutical drug comprising three chimeric monoclonal antibodies under development as a treatment for Ebola virus disease. Two of the three components were originally developed at the Public Health Agency of Canada's National Microbiology Laboratory (NML), and the third at the U.S. Army Medical Research Institute of Infectious Diseases; the cocktail was optimized by Gary Kobinger, a research scientist at the NML and underwent further development under license by Mapp Biopharmaceutical. ZMapp was first used on humans during the Western African Ebola virus epidemic, having only been previously tested on animals and not yet subjected to a randomized controlled trial. The National Institutes of Health (NIH) ran a clinical trial starting in January 2015 with subjects from Sierra Leone, Guinea, and Liberia aiming to enroll 200 people, but the epidemic waned and the trial closed early, leaving it too statistically underpowered to give a meaningful result about whether ZMapp worked.

TKM-Ebola was an experimental antiviral drug for Ebola disease that was developed by Arbutus Biopharma in Vancouver, Canada. The drug candidate was formerly known as Ebola-SNALP.

Ebola vaccines are vaccines either approved or in development to prevent Ebola. As of 2022, there are only vaccines against the Zaire ebolavirus. The first vaccine to be approved in the United States was rVSV-ZEBOV in December 2019. It had been used extensively in the Kivu Ebola epidemic under a compassionate use protocol. During the early 21st century, several vaccine candidates displayed efficacy to protect nonhuman primates against lethal infection.

Galidesivir is an antiviral drug, an adenosine analog. It was developed by BioCryst Pharmaceuticals with funding from NIAID, originally intended as a treatment for hepatitis C, but subsequently developed as a potential treatment for deadly filovirus infections such as Ebola virus disease and Marburg virus disease, as well as Zika virus. Currently, galidesivir is under phase 1 human trial in Brazil for coronavirus.

The 2018 Équateur province Ebola outbreak occurred in the north-west of the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC) from May to July 2018. It was contained entirely within Équateur province, and was the first time that vaccination with the rVSV-ZEBOV Ebola vaccine had been attempted in the early stages of an Ebola outbreak, with a total of 3,481 people vaccinated. It was the ninth recorded Ebola outbreak in the DRC.

Ansuvimab, sold under the brand name Ebanga, is a monoclonal antibody medication for the treatment of Zaire ebolavirus (Ebolavirus) infection.

COVID-19 drug development is the research process to develop preventative therapeutic prescription drugs that would alleviate the severity of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19). From early 2020 through 2021, several hundred drug companies, biotechnology firms, university research groups, and health organizations were developing therapeutic candidates for COVID-19 disease in various stages of preclinical or clinical research, with 419 potential COVID-19 drugs in clinical trials, as of April 2021.

Convalescent plasma is the blood plasma collected from a survivor of an infectious disease. This plasma contains antibodies specific to a pathogen and can be used therapeutically by providing passive immunity when transfusing it to a newly infected patient with the same condition. Convalescent plasma can be transfused as it has been collected or become the source material for the hyperimmune serum which consists largely of IgG but also includes IgA and IgM. or as source material for anti-pathogen monoclonal antibodies, Collection is typically achieved by apheresis, but in low-to-middle income countries, the treatment can be administered as convalescent whole blood.

Atoltivimab/maftivimab/odesivimab, sold under the brand name Inmazeb, is a fixed-dose combination of three monoclonal antibodies for the treatment of Zaire ebolavirus. It contains atoltivimab, maftivimab, and odesivimab-ebgn and was developed by Regeneron Pharmaceuticals.

Gary P. Kobinger is a Canadian immunologist and virologist who is currently the director at the Galveston National Laboratory at the University of Texas. He has held previous professorships at Université Laval, the University of Manitoba, and the University of Pennsylvania. Additionally, he was the chief of the Special Pathogens Unit at the National Microbiology Laboratory (NML) of the Public Health Agency of Canada (PHAC) in Winnipeg, Manitoba, for eight years. Kobinger is known for his critical role in the development of both an effective Ebola vaccine and treatment. His work focuses on the development and evaluation of new vaccine platforms and immunological treatments against emerging and re-emerging viruses that are dangerous to human health.