Fort Wool is a decommissioned island fortification located in the mouth of Hampton Roads, adjacent to the Hampton Roads Bridge-Tunnel (HRBT). Officially known as Rip Raps Island, the fort has an elevation of 7 feet and sits near Old Point Comfort, Old Point Comfort Light, Willoughby Beach and Willoughby Spit, approximately one mile south of Fort Monroe.

Fort William and Mary was a colonial fortification in Britain's worldwide system of defenses, defended by soldiers of the Province of New Hampshire who reported directly to the royal governor. The fort, originally known as "The Castle," was situated on the island of New Castle, New Hampshire, at the mouth of the Piscataqua River estuary. It was renamed Fort William and Mary circa 1692, after the accession of the monarchs William III and Mary II to the British throne. It was captured by Patriot forces, recaptured, and later abandoned by the British in the Revolutionary War. The fort was renamed Fort Constitution in 1808 following rebuilding. The fort was further rebuilt and expanded through 1899 and served actively through World War II.

Fort Moultrie is a series of fortifications on Sullivan's Island, South Carolina, built to protect the city of Charleston, South Carolina. The first fort, formerly named Fort Sullivan, built of palmetto logs, inspired the flag and nickname of South Carolina, as "The Palmetto State". The fort was renamed for the U.S. patriot commander in the Battle of Sullivan's Island, General William Moultrie. During British occupation, in 1780–1782, the fort was known as Fort Arbuthnot.

Fort McClary is a former defensive fortification of the United States military located along the southern coast at Kittery Point, Maine at the mouth of the Piscataqua River. It was used throughout the 19th century to protect approaches to the harbor of Portsmouth, New Hampshire and the Portsmouth Naval Shipyard in Kittery. The property and its surviving structures are now owned and operated by the State of Maine as Fort McClary State Historic Site, including a blockhouse dating from 1844.

Castle Island is a peninsula in South Boston on the shore of Boston Harbor. In 1928, Castle Island was connected to the mainland by a narrow strip of land and is thus no longer an island. It has been the site of a fortification since 1634, and is currently a 22-acre (8.9 ha) recreation site and the location of Fort Independence.

House Island is a private island in Portland Harbor in Casco Bay, Maine, United States. It is part of the City of Portland. The island is accessible only by boat. Public access is prohibited, except for an on-request tour sanctioned by the island's owners. House Island includes three buildings on the east side and Fort Scammell on the west side. The buildings are used as vacation rentals and other summer residences. The island's name derives from the site of an early European house, believed that built by Capt. Christopher Levett, an English explorer of the region.

Fort Jay is a coastal bastion fort and the name of a former United States Army post on Governors Island in New York Harbor, within New York City. Fort Jay is the oldest existing defensive structure on the island, and was named for John Jay, a member of the Federalist Party, New York governor, Chief Justice of the United States, Secretary of State, and one of the Founding Fathers of the United States. It was built in 1794 to defend Upper New York Bay, but has served other purposes. From 1806 to 1904 it was named Fort Columbus, presumably for explorer Christopher Columbus. Today, the National Park Service administers Fort Jay and Castle Williams as the Governors Island National Monument.

Fort Delaware is a former harbor defense facility, designed by chief engineer Joseph Gilbert Totten and located on Pea Patch Island in the Delaware River. During the American Civil War, the Union used Fort Delaware as a prison for Confederate prisoners of war, political prisoners, federal convicts, and privateer officers. A three-gun concrete battery of 12-inch guns, later named Battery Torbert, was designed by Maj. Charles W. Raymond and built inside the fort in the 1890s. By 1900, the fort was part of a three fort concept, the first forts of the Coast Defenses of the Delaware, working closely with Fort Mott in Pennsville, New Jersey, and Fort DuPont in Delaware City, Delaware. The fort and the island currently belong to the Delaware Department of Natural Resources and Environmental Control (DNREC) and encompass a living history museum, located in Fort Delaware State Park.

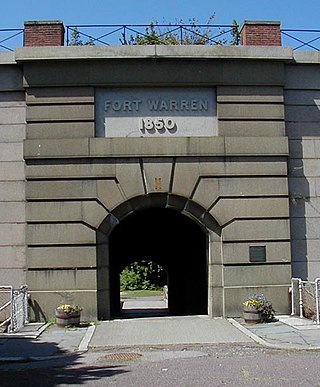

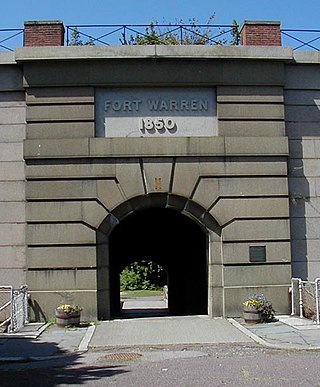

Fort Warren is a historic fort on the 28-acre (110,000 m2) Georges Island at the entrance to Boston Harbor. The fort is named for Revolutionary War hero Dr. Joseph Warren, who sent Paul Revere on his famous ride, and was later killed at the Battle of Bunker Hill. The name was transferred in 1833 from the first Fort Warren – built in 1808 – which was renamed Fort Winthrop.

Long Island is located in Boston Harbor, Massachusetts. The island is part of the City of Boston, and of the Boston Harbor Islands National Recreation Area. The island is 1.75 miles (2.82 km) long and covers 225 acres (0.9 km2).

A floating battery is a kind of armed watercraft, often improvised or experimental, which carries heavy armament but has few other qualities as a warship.

The Battle of Chelsea Creek was the second military engagement of the Boston campaign of the American Revolutionary War. It is also known as the Battle of Noddle's Island, Battle of Hog Island and the Battle of the Chelsea Estuary. This battle was fought on May 27 and 28, 1775, on Chelsea Creek and on salt marshes, mudflats, and islands of Boston Harbor, northeast of the Boston peninsula. Most of these areas have since been united with the mainland by land reclamation and are now part of East Boston, Chelsea, Winthrop, and Revere.

Seacoast defense was a major concern for the United States from its independence until World War II. Before airplanes, many of America's enemies could only reach it from the sea, making coastal forts an economical alternative to standing armies or a large navy. After the 1940s, it was recognized that fixed fortifications were obsolete and ineffective against aircraft and missiles. However, in prior eras foreign fleets were a realistic threat, and substantial fortifications were built at key locations, especially protecting major harbors.

Fort Phoenix is a former American Revolutionary War-era fort located at the entrance to the Fairhaven-New Bedford harbor, south of U.S. 6 in Fort Phoenix Park in Fairhaven, Massachusetts. The fort was originally built in 1775 without a name, and added to the National Register of Historic Places in 1972. Just off the fort, in Buzzards Bay, was the first naval engagement of the American Revolution, the Battle off Fairhaven on 14 May 1775.

Fort Pickering is a 17th-century historic fort site on Winter Island in Salem, Massachusetts. Fort Pickering operated as a strategic coastal defense and military barracks for Salem Harbor during a variety of periods, serving as a fortification from the Anglo-Dutch Wars through World War II. Construction of the original fort began in 1643 and it saw use as a military installation into the 20th century. Fort Miller in Marblehead also defended Salem's harbor from the 1630s through the American Civil War. Fort Pickering is a First System fortification named for Colonel Timothy Pickering, born in Salem, adjutant general of the Continental Army and secretary of war in 1795. Today, the remains of the fort are open to the public as part of the Winter Island Maritime Park, operated by the City of Salem.

Fort Sewall is a historic coastal fortification in Marblehead, Massachusetts. It is located at Gale's Head, the northeastern point of the main Marblehead peninsula, on a promontory that overlooks the entrance to Marblehead Harbor. Until 1814 it was called Gale's Head Fort.

Fort Revere is an 8-acre (3.2 ha) historic site situated on a small peninsula located in Hull, Massachusetts. It is situated on Telegraph Hill in Hull Village and contains the remains of two seacoast fortifications, one from the American Revolution and one that served 1898–1947. There are also a water tower with an observation deck, a military history museum and picnic facilities. It is operated as Fort Revere Park by the Metropolitan Park System of Greater Boston.

Fort Stark is a former military fortification in New Castle, New Hampshire, United States. Located at Jerry's Point on the southeastern tip of New Castle Island, most of the surviving fort was developed in the early 20th century, following the Spanish–American War, although there were several earlier fortifications on the site, portions of which survive. The fort was named for John Stark, a New Hampshire officer who distinguished himself at the Battle of Bennington in the American Revolution. The purpose of Fort Stark was to defend the harbor of nearby Portsmouth and the Portsmouth Naval Shipyard. The fort remained in active use through the Second World War, after which it was used for reserve training by the US Navy. The property was partially turned over to the state of New Hampshire in 1979, which established Fort Stark Historic Site, and the remainder of the property was turned over in 1983. The grounds are open to the public during daylight hours.

The Harbor Defenses of Portsmouth was a United States Army Coast Artillery Corps harbor defense command. It coordinated the coast defenses of Portsmouth, New Hampshire and the nearby Portsmouth Naval Shipyard in Kittery, Maine from 1900 to 1950, both on the Piscataqua River, beginning with the Endicott program. These included both coast artillery forts and underwater minefields. The command originated circa 1900 as the Portsmouth Artillery District, was renamed Coast Defenses of Portsmouth in 1913, and again renamed Harbor Defenses of Portsmouth in 1925.

The Harbor Defenses of Boston was a United States Army Coast Artillery Corps harbor defense command. It coordinated the coast defenses of Boston, Massachusetts from 1895 to 1950, beginning with the Endicott program. These included both coast artillery forts and underwater minefields. The command originated circa 1895 as the Boston Artillery District, was renamed Coast Defenses of Boston in 1913, and again renamed Harbor Defenses of Boston in 1925.