In the Gaelic-speaking parts of Scotland, the use of the Gaelic language on road signs instead of, or more often alongside, English is now common, but has been a controversial issue.

In the Gaelic-speaking parts of Scotland, the use of the Gaelic language on road signs instead of, or more often alongside, English is now common, but has been a controversial issue.

In the 18th and 19th centuries, map makers recorded Gaelic placenames in Anglicised versions. One would expect important towns like Stornoway or Portree to have slightly different names in different languages, but it is unusual for this to be the case with small hamlets or minor topographical features, and the Anglicisation of placenames was resented by educated Gaels. [1]

In the 20th century, Inverness County Council, which until the latter part of the century was known for its antipathy towards the Gaelic language, was responsible for erecting road signs throughout the Highlands. [1] The council insisted that these be entirely in English and follow the spellings on the Ordnance Survey maps. Gaelic language organisations had limited resources and thus did not see opposition to this policy as a priority. In September 1970 Aird District Council rejected a proposal for bilingual signs. [2]

In 1973, however, the issue was forced onto the public agenda as a result of the Skye road sign controversy. The council was planning to build a new road south from Portree, and needed to purchase a strip of land belonging to landowner Iain Noble. Noble offered to donate the land to the council on condition that the three signs which were to be erected on the stretch of road be bilingual, a way of registering Gaelic on the linguistic landscape. The proposal was fiercely resisted by the council, and in particular by Lord Burton, Chairman of the Roads Committee, who later the same year attempted unsuccessfully to introduce legislation in the House of Lords limiting the use of Gaelic by Scottish local authorities. However, Noble was supported by a petition signed by many prominent Skye residents, and the experience of Wales, where bilingual signposting had already been accepted, was favourable. As the issue had aroused public interest, and a compulsory purchase order might have been slow and expensive, the council negotiated a compromise: Portree and Broadford both received bilingual signposts on an "experimental" basis. [1]

As Noble had hoped, and the council feared, this set a precedent, which was gradually followed throughout the 1980s, becoming generally accepted in the 1990s. Bilingual signposting is now the norm throughout the Western Isles (indeed for a time directional signposts there were monolingually Gaelic [3] ) and also in large parts of the mainland on local authority roads.

In 1996, Highland Council decided to make use of Gaelic-only signposts in some areas. [4]

In 2001, the Scottish Government announced plans to erect bilingual signage along many of the trunk roads in the Scottish Highlands, [5] in addition to those already erected on local-authority-maintained roads. This project is now all but completed, although importantly it excludes the main A9 trunk road and also the A96 between Inverness and Aberdeen. It has however included the A82 westerly trunk route from Inverness to Glasgow. Since the government has a strict policy of only erecting bilingual roadsigns when new signs in any case had to be erected, the costs to the public purse of making these bilingual has been negligible.

In 2008, eight Caithness councillors were unsuccessful in their attempt to block Highland-wide support for bilingual English/Gaelic signage. [6]

In March 2009, Highland Council's Gaelic committee wrote to the Transport Minister, Stewart Stevenson, asking for the use of Gaelic signage to be extended on trunk roads. The minister responded by saying that he awaited a review that had been commissioned, as he thought there was some anecdotal evidence of motorists encountering some difficulties with bilingual signage. [7]

A report was published in 2012 by Transport Scotland stating that bilingual signs were not a danger to motorists. It was noted that the signs required slightly more attention on the part of motorists but that it did not pose any real risk. According to the study there has been no detectable change in accident rates. [8]

"The report suggests that while there is reasonable evidence to infer bilingual signs increase the demand of the driving task, drivers appear able to absorb this extra demand, or negate it by slowing down, which ultimately results in no detectable change in accident rates."

— Consultant, TRL, [8]

Research conducted by Leeds University indicates that multi-lingual signs consisting of four or more lines of text can cause drivers to brake to allow them time to process the additional information. Following drivers may not react appropriately to the change in speed of the leading vehicle. The study recommends the use of "separation techniques", such as using a different colour of font for each language, which eliminates the problem. [9] Bilingual road signs in Scotland typically use white letters for English and yellow for Gaelic.

Scottish Gaelic, also known as Scots Gaelic or simply Gaelic, is a Goidelic language native to the Gaels of Scotland. As a Goidelic language, Scottish Gaelic, as well as both Irish and Manx, developed out of Old Irish. It became a distinct spoken language sometime in the 13th century in the Middle Irish period, although a common literary language was shared by the Gaels of both Ireland and Scotland until well into the 17th century. Most of modern Scotland was once Gaelic-speaking, as evidenced especially by Gaelic-language place names.

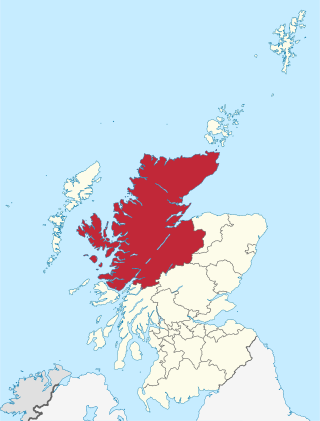

Highland is a council area in the Scottish Highlands and is the largest local government area in the United Kingdom. It was the 7th most populous council area in Scotland at the 2011 census. It shares borders with the council areas of Aberdeenshire, Argyll and Bute, Moray and Perth and Kinross. Their councils, and those of Angus and Stirling, also have areas of the Scottish Highlands within their administrative boundaries.

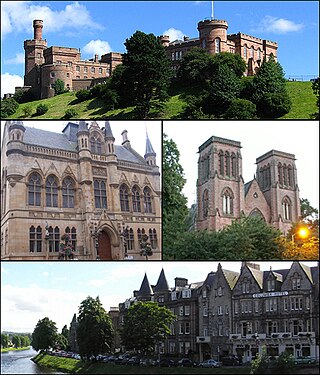

Inverness is one of the eight cities of Scotland and is located in the Scottish Highlands, having been granted city status in 2000. It is the administrative centre for The Highland Council and is regarded as the capital of the Highlands.

The A82 is a major road in Scotland that runs from Glasgow to Inverness via Fort William. It is one of the principal north-south routes in Scotland and is mostly a trunk road managed by Transport Scotland, who view it as an important link from the Central Belt to the Scottish Highlands and beyond. The road passes close to numerous landmarks, including Loch Lomond, Rannoch Moor, Glen Coe, the Ballachulish Bridge, Ben Nevis, the Commando Memorial, Loch Ness, and Urquhart Castle. Along with the A9 and the A90 it is one of the three major north–south trunk roads connecting the Central Belt to the North.

Portree is the largest town on, and capital of, the Isle of Skye in the Inner Hebrides of Scotland. It is the location for the only secondary school on the island, Portree High School. Public transport services are limited to buses. Portree has a harbour, fringed by cliffs, with a pier designed by Thomas Telford.

Caithness is a historic county, registration county and lieutenancy area of Scotland.

The Gàidhealtachd usually refers to the Highlands and Islands of Scotland and especially the Scottish Gaelic-speaking culture of the area. The similar Irish language word Gaeltacht refers, however, solely to Irish-speaking areas.

Sleat is a peninsula and civil parish on the island of Skye in the Highland council area of Scotland, known as "the garden of Skye". It is the home of the clan MacDonald of Sleat. The name comes from the Scottish Gaelic Slèite, which in turn comes from Old Norse sléttr, which well describes Sleat when considered in the surrounding context of the mainland, Skye and Rùm mountains that dominate the horizon all about Sleat.

Glenelg is a scattered community area and civil parish in the Lochalsh area of Highland in western Scotland. Despite the local government reorganisation the area is considered by many still to be in Inverness-shire, the boundary with Ross-shire being at the top of Mam Ratagan the single-track road entry into Glenelg.

Uig is a village at the head of Uig Bay on the west coast of the Trotternish peninsula on the Isle of Skye, Scotland. In 2011 it had a population of 423.

Scottish Gaelic-medium education, also known as Gaelic-medium education (GME), is a form of education in Scotland that allows pupils to be taught primarily through the medium of Scottish Gaelic, with English being taught as the secondary language.

Heasta, Heast, or the anglicised form Heaste, pron. /heɪst/, is a small settlement on the island of Skye, Scotland. It is located on the west coast of the island five miles south of Broadford extending down to the north shore of Loch Eiseort, facing out to the Atlantic to the south west and is in the Scottish council area of Highland.

The Isle of Skye, or simply Skye, is the largest and northernmost of the major islands in the Inner Hebrides of Scotland. The island's peninsulas radiate from a mountainous hub dominated by the Cuillin, the rocky slopes of which provide some of the most dramatic mountain scenery in the country. Although Sgitheanach has been suggested to describe a winged shape, no definitive agreement exists as to the name's origins.

Staffin is a district with the Gaelic name An Taobh Sear, which translates as "the East Side", on the northeast coast of the Trotternish peninsula of the island of Skye. It is located on the A855 road about 17 miles north of Portree and is overlooked by the Trotternish Ridge with the famous rock formations of The Storr and the Quiraing. The district comprises 23 townships made up of, from south to north, Rigg, Tote, Lealt, Lonfearn, Grealin, Breackry, Cul-nan-cnoc, Bhaltos, Raiseburgh, Ellishadder, Garafad, Clachan, Garros, Marrishader, Maligar, Stenscholl, Brogaig, Sartle, Glasphein, Digg, Dunan, Flodigarry and Greap. The Kilmartin River runs northwards through the village. From where it reaches the sea a rocky shore leads east to a slipway at An Corran. Here a local resident found a slab bearing a dinosaur track, probably made by a small ornithopod. Experts subsequently found more dinosaur prints of up to 50 cm, the largest found in Scotland, made by a creature similar to Megalosaurus. At about 160 million years old they are the youngest dinosaur remains to be found in Scotland.

Inverness-shire is a historic county, registration county and lieutenancy area of Scotland. Covering much of the Highlands and Outer Hebrides, it is Scotland's largest county, though one of the smallest in population, with 67,733 people or 1.34% of the Scottish population.

Duirinish is a peninsula and civil parish on the island of Skye in Scotland. It is situated in the north west between Loch Dunvegan and Loch Bracadale.

Road signs in Wales follow the same design principles as those in other parts of the United Kingdom. All modern signs feature both Welsh- and English-language wording, with Welsh first signage present in some areas of Wales and mandated for all new signs, but some English first signage remains when it was legally allowed before 2016.

Mugeary is a farm or croft and former settlement on the island of Skye, Scotland. Located 4 kilometres southwest of Portree, it is known as the location where the basaltic rock mugearite was first identified. The Gaelic name is derived from Old Norse and probably means "narrow field".

Lochalsh is a district of mainland Scotland that is currently part of the Highland council area. The Lochalsh district covers all of the mainland either side of Loch Alsh - and of Loch Duich - between Loch Carron and Loch Hourn, ie. from Stromeferry in the north on Loch Carron down to Corran on Loch Hourn and as (south-)west as Kintail. It was sometimes more narrowly defined as just being the hilly peninsula that lies between Loch Carron and Loch Alsh. The main settlement is Kyle of Lochalsh, located at the entrance to Loch Alsh, opposite the village of Kyleakin on the adjacent island of Skye. A ferry used to connect the two settlements but was replaced by the Skye Bridge in 1995.

Mary MacPherson (née MacDonald), known as Màiri Mhòr nan Òran or simply Màiri Mhòr, was a Scottish Gaelic poet from the Isle of Skye, whose contribution to Scottish Gaelic literature is focused heavily upon the Highland Clearances and the Crofters War; the Highland Land League's campaigns of rent strikes and other forms of direct action. Although she could read her own work when it was written down, she could not write it down herself. She retained her songs and poems in her memory and eventually dictated them to others, who wrote them down for publication. She often referred to herself as Màiri Nighean Iain Bhàin, the name by which she would have been known in the Skye of her childhood.