The Isle of Man is an island in the Irish Sea, between Great Britain and Ireland in Northern Europe, with a population of almost 85,000. It is a British Crown dependency. It has a small islet, the Calf of Man, to its south. It is located at 54°15′N4°30′W.

Ramsey is a coastal town in the north of the Isle of Man. It is the second largest town on the island after Douglas. Its population is 7,845 according to the 2016 Census. It has one of the biggest harbours on the island, and has a prominent derelict pier, called the Queen's Pier. It was formerly one of the main points of communication with Scotland. Ramsey has also been a route for several invasions by the Vikings and Scots.

Luing is one of the Slate Islands, Firth of Lorn, in the west of Argyll in Scotland, about 16 miles (26 km) south of Oban. The island has an area of 1,430 hectares and is bounded by several small skerries and islets. It has a population of around 200 people, mostly living in Cullipool, Toberonochy, and Blackmillbay.

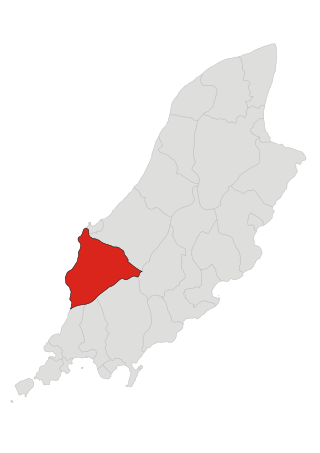

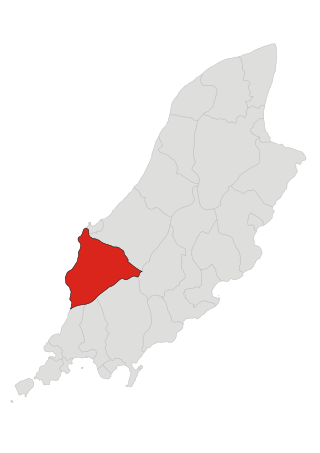

St John's is a small village in the sheading of Glenfaba in the Isle of Man, in the island's central valley. It is in the House of Keys constituency of Glenfaba & Peel, which elects two MHKs.

The geology of Scotland is unusually varied for a country of its size, with a large number of different geological features. There are three main geographical sub-divisions: the Highlands and Islands is a diverse area which lies to the north and west of the Highland Boundary Fault; the Central Lowlands is a rift valley mainly comprising Palaeozoic formations; and the Southern Uplands, which lie south of the Southern Uplands Fault, are largely composed of Silurian deposits.

Patrick is one of the seventeen historic parishes of the Isle of Man.

Cammag is a team sport originating on the Isle of Man. It is closely related to the Scottish game of shinty and the Irish game of hurling. Once the most widespread sport on Mann, it ceased to be played in the early twentieth century after the introduction of association football and is no longer an organised sport.

The Isle of Man is mostly hilly, but has only one summit, Snaefell, classified as a mountain.

The geology of the Isle of Skye in Scotland is highly varied and the island's landscape reflects changes in the underlying nature of the rocks. A wide range of rock types are exposed on the island, sedimentary, metamorphic and igneous, ranging in age from the Archaean through to the Quaternary.

The geology of County Durham in northeast England consists of a basement of Lower Palaeozoic rocks overlain by a varying thickness of Carboniferous and Permo-Triassic sedimentary rocks which dip generally eastwards towards the North Sea. These have been intruded by a pluton, sills and dykes at various times from the Devonian Period to the Palaeogene. The whole is overlain by a suite of unconsolidated deposits of Quaternary age arising from glaciation and from other processes operating during the post-glacial period to the present. The geological interest of the west of the county was recognised by the designation in 2003 of the North Pennines Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty as a European Geopark.

The geology of Tyne and Wear in northeast England largely consists of a suite of sedimentary rocks dating from the Carboniferous and Permian periods into which were intruded igneous dykes during the later Palaeogene Period.

The Great Scar Limestone Group is a lithostratigraphical term referring to a succession of generally fossiliferous rock strata which occur in the Pennines in northern England and in the Isle of Man within the Tournaisian and Visean stages of the Carboniferous Period.

The geology of Northumberland in northeast England includes a mix of sedimentary, intrusive and extrusive igneous rocks from the Palaeozoic and Cenozoic eras. Devonian age volcanic rocks and a granite pluton form the Cheviot massif. The geology of the rest of the county is characterised largely by a thick sequence of sedimentary rocks of Carboniferous age. These are intruded by both Permian and Palaeogene dykes and sills and the whole is overlain by unconsolidated sediments from the last ice age and the post-glacial period. The Whin Sill makes a significant impact on Northumberland's character and the former working of the Northumberland Coalfield significantly influenced the development of the county's economy. The county's geology contributes to a series of significant landscape features around which the Northumberland National Park was designated.

The Foxdale Mines is a collective term for a series of mines and shafts which were situated in a highly mineralised zone on the Isle of Man, running east to west, from Elerslie mine in Crosby to Niarbyl on the coast near Dalby. In the 19th century the mines were widely regarded as amongst the richest ore mines in the British Isles.

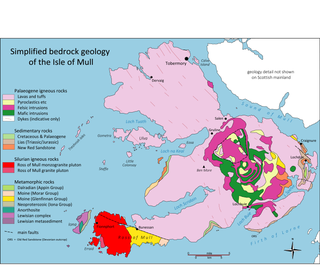

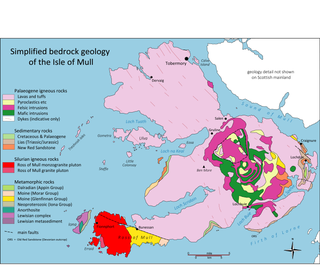

The Manx Group is an Ordovician lithostratigraphic group in the Isle of Man in the Irish Sea. The name is derived from the name of the island which is largely formed from them; these rocks have also previously been referred to as the Manx Slates or Manx Slates Series. The group comprises dark mudstones with siltstone laminae and some sandstones and which exceed a thickness of 3000m. It is divided into a lowermost Glen Dhoo Formation which is overlain by the Lonan, Mull Hill, Creg Agneash and Maughold formations in ascending order. A fault separates these from the overlying Barrule, Injebreck, Glen Rushen and Creggan Mooar formations which are in turn separated by a fault from an overlying Ladyport Formation.

The Dalby Group is a Silurian lithostratigraphic group on the west coast of the Isle of Man in the Irish Sea. The name is derived from the village of Dalby near the west coast of the island. Together with those of the adjoining Manx Group, the rocks of the Group have also previously been referred to as the Manx Slates or Manx Slate Series. The group comprises wacke sandstones with siltstones and mudstones which reach a thickness of about 1200m in the west of the island. It contains only the single Niarbyl Formation which is exposed along the coast between Niarbyl Point and the town of Peel to the north.

The geology of Northumberland National Park in northeast England includes a mix of sedimentary, intrusive and extrusive igneous rocks from the Palaeozoic and Cenozoic eras. Devonian age volcanic rocks and a granite pluton form the Cheviot massif. The geology of the rest of the national park is characterised largely by a thick sequence of sedimentary rocks of Carboniferous age. These are intruded by Permian dykes and sills, of which the Whin Sill makes a significant impact in the south of the park. Further dykes were intruded during the Palaeogene period. The whole is overlain by unconsolidated sediments from the last ice age and the post-glacial period.

The geology of the Isle of Mull in Scotland is dominated by the development during the early Palaeogene period of a ‘volcanic central complex’ associated with the opening of the Atlantic Ocean. The bedrock of the larger part of the island is formed by basalt lava flows ascribed to the Mull Lava Group erupted onto a succession of Mesozoic sedimentary rocks during the Palaeocene epoch. Precambrian and Palaeozoic rocks occur at the island's margins. A number of distinct deposits and features such as raised beaches were formed during the Quaternary period.

The geology of Anglesey, the largest (714 km2) island in Wales is some of the most complex in the country. Anglesey has relatively low relief, the 'grain' of which runs northeast–southwest, i.e. ridge and valley features extend in that direction reflecting not only the trend of the late Precambrian and Palaeozoic age bedrock geology but also the direction in which glacial ice traversed and scoured the island during the last ice age. It was realised in the 1980s that the island is composed of multiple terranes, recognition of which is key to understanding its Precambrian and lower Palaeozoic evolution. The interpretation of the island's geological complexity has been debated amongst geologists for decades and recent research continues in that vein.

The geology of the Yorkshire Dales National Park in northern England largely consists of a sequence of sedimentary rocks of Ordovician to Permian age. The core area of the Yorkshire Dales is formed from a layer-cake of limestones, sandstones and mudstones laid down during the Carboniferous period. It is noted for its karst landscape which includes extensive areas of limestone pavement and large numbers of caves including Britain's longest cave network.