A cyst is a closed sac, having a distinct envelope and division compared with the nearby tissue. Hence, it is a cluster of cells that have grouped together to form a sac ; however, the distinguishing aspect of a cyst is that the cells forming the "shell" of such a sac are distinctly abnormal when compared with all surrounding cells for that given location. A cyst may contain air, fluids, or semi-solid material. A collection of pus is called an abscess, not a cyst. Once formed, a cyst may resolve on its own. When a cyst fails to resolve, it may need to be removed surgically, but that would depend upon its type and location.

Ameloblastoma is a rare, benign or cancerous tumor of odontogenic epithelium much more commonly appearing in the lower jaw than the upper jaw. It was recognized in 1827 by Cusack. This type of odontogenic neoplasm was designated as an adamantinoma in 1885 by the French physician Louis-Charles Malassez. It was finally renamed to the modern name ameloblastoma in 1930 by Ivey and Churchill.

Cementoblastoma, or benign cementoblastoma, is a relatively rare benign neoplasm of the cementum of the teeth. It is derived from ectomesenchyme of odontogenic origin. Cementoblastomas represent less than 0.69–8% of all odontogemic tumors.

Mucoepidermoid carcinoma (MEC) is the most common type of minor salivary gland malignancy in adults. Mucoepidermoid carcinoma can also be found in other organs, such as bronchi, lacrimal sac, and thyroid gland.

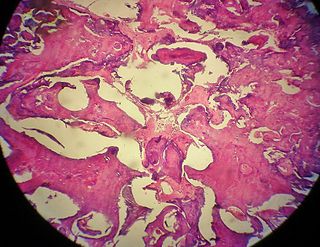

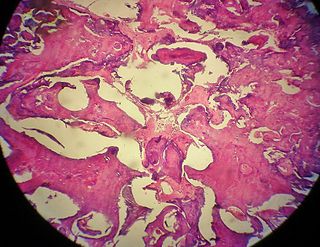

Dentigerous cyst, also known as follicular cyst is an epithelial-lined developmental cyst formed by accumulation of fluid between the reduced enamel epithelium and crown of an unerupted tooth. It is formed when there is an alteration in the reduced enamel epithelium and encloses the crown of an unerupted tooth at the cemento-enamel junction. Fluid is accumulated between reduced enamel epithelium and the crown of an unerupted tooth. Dentigerous cyst is the second most common form of benign developmental odontogenic cysts.

Central giant-cell granuloma (CGCG) is a localised benign condition of the jaws. It is twice as common in females and is more likely to occur before age 30. Central giant-cell granulomas are more common in the anterior mandible, often crossing the midline and causing painless swellings.

Commonly known as a dental cyst, the periapical cyst is the most common odontogenic cyst. It may develop rapidly from a periapical granuloma, as a consequence of untreated chronic periapical periodontitis.

An odontogenic keratocyst is a rare and benign but locally aggressive developmental cyst. It most often affects the posterior mandible and most commonly presents in the third decade of life. Odontogenic keratocysts make up around 19% of jaw cysts.

“Lateral periodontal cysts (LPCs) are defined as non-keratinised and non-inflammatory developmental cysts located adjacent or lateral to the root of a vital tooth.” LPCs are a rare form of jaw cysts, with the same histopathological characteristics as gingival cysts of adults (GCA). Hence LPCs are regarded as the intraosseous form of the extraosseous GCA. They are commonly found along the lateral periodontium or within the bone between the roots of vital teeth, around mandibular canines and premolars. Standish and Shafer reported the first well-documented case of LPCs in 1958, followed by Holder and Kunkel in the same year although it was called a periodontal cyst. Since then, there has been more than 270 well-documented cases of LPCs in literature.

Calcifying odotogenic cyst (COC) is a rare developmental lesion that comes from odontogenic epithelium. It is also known as a calcifying cystic odontogenic tumor, which is a proliferation of odontogenic epithelium and scattered nest of ghost cells and calcifications that may form the lining of a cyst, or present as a solid mass.

Squamous odontogenic tumors (SOTs) are very rare benign locally infiltrative odontogenic neoplasms of epithelial origin. Only some 50 cases have been documented. They occur mostly from 20-40 and are more common in males. Treatment is by simple enucleation and local curettage, and recurrence is rare.

An ameloblastic fibroma is a fibroma of the ameloblastic tissue, that is, an odontogenic tumor arising from the enamel organ or dental lamina. It may be either truly neoplastic or merely hamartomatous. In neoplastic cases, it may be labeled an ameloblastic fibrosarcoma in accord with the terminological distinction that reserves the word fibroma for benign tumors and assigns the word fibrosarcoma to malignant ones. It is more common in the first and second decades of life, when odontogenesis is ongoing, than in later decades. In 50% of cases an unerupted tooth is involved.

An odontoma, also known as an odontome, is a benign tumour linked to tooth development. Specifically, it is a dental hamartoma, meaning that it is composed of normal dental tissue that has grown in an irregular way. It includes both odontogenic hard and soft tissues. As with normal tooth development, odontomas stop growing once mature which makes them benign.

The odontogenic myxoma is an uncommon benign odontogenic tumor arising from embryonic connective tissue associated with tooth formation. As a myxoma, this tumor consists mainly of spindle shaped cells and scattered collagen fibers distributed through a loose, mucoid material.

The calcifying epithelial odontogenic tumor (CEOT), also known as a Pindborg tumor, is an odontogenic tumor first recognized by the Danish pathologist Jens Jørgen Pindborg in 1955. It was previously described as an adenoid adamantoblastoma, unusual ameloblastoma and a cystic odontoma. Like other odontogenic neoplasms, it is thought to arise from the epithelial element of the enamel origin. It is a typically benign and slow growing, but invasive neoplasm.

An odontogenic infection is an infection that originates within a tooth or in the closely surrounding tissues. The term is derived from odonto- and -genic. The most common causes for odontogenic infection to be established are dental caries, deep fillings, failed root canal treatments, periodontal disease, and pericoronitis. Odontogenic infection starts as localised infection and may remain localised to the region where it started, or spread into adjacent or distant areas.

Odontogenic cyst are a group of jaw cysts that are formed from tissues involved in odontogenesis. Odontogenic cysts are closed sacs, and have a distinct membrane derived from rests of odontogenic epithelium. It may contain air, fluids, or semi-solid material. Intra-bony cysts are most common in the jaws, because the mandible and maxilla are the only bones with epithelial components. That odontogenic epithelium is critical in normal tooth development. However, epithelial rests may be the origin for the cyst lining later. Not all oral cysts are odontogenic cyst. For example, mucous cyst of the oral mucosa and nasolabial duct cyst are not of odontogenic origin.

In addition, there are several conditions with so-called (radiographic) 'pseudocystic appearance' in jaws; ranging from anatomic variants such as Stafne static bone cyst, to the aggressive aneurysmal bone cyst.

A cyst is a pathological epithelial lined cavity that fills with fluid or soft material and usually grows from internal pressure generated by fluid being drawn into the cavity from osmosis. The bones of the jaws, the mandible and maxilla, are the bones with the highest prevalence of cysts in the human body. This is due to the abundant amount of epithelial remnants that can be left in the bones of the jaws. The enamel of teeth is formed from ectoderm, and so remnants of epithelium can be left in the bone during odontogenesis. The bones of the jaws develop from embryologic processes which fuse together, and ectodermal tissue may be trapped along the lines of this fusion. This "resting" epithelium is usually dormant or undergoes atrophy, but, when stimulated, may form a cyst. The reasons why resting epithelium may proliferate and undergo cystic transformation are generally unknown, but inflammation is thought to be a major factor. The high prevalence of tooth impactions and dental infections that occur in the bones of the jaws is also significant to explain why cysts are more common at these sites.

A median mandibular cyst is a type of cyst that occurs in the midline of the mandible, thought to be created by proliferation and cystic degeneration of resting epithelial tissue that is left trapped within the substance of the bone during embryologic fusion of the two halves of the mandible, along the plane of fusion later termed the symphysis menti. A true median mandibular cyst would therefore be classified as a non-odontogenic, fissural cyst. The existence of this lesion as a unique clinical entity is controversial, and some reported cases may have represented misdiagnosed odontogenic cysts, which are by far the most common type of intrabony cyst occurring in the jaws. It has also been suggested that the mandible develops as a bilobed proliferation of mesenchyme connected with a central isthmus. Therefore, it is unlikely that epithelial tissue would become trapped as there is no ectoderm separating the lobes in the first instance.

Gingival cyst, also known as Epstein's pearl, is a type of cysts of the jaws that originates from the dental lamina and is found in the mouth parts. It is a superficial cyst in the alveolar mucosa. It can be seen inside the mouth as small and whitish bulge. Depending on the ages in which they develop, the cysts are classified into gingival cyst of newborn and gingival cyst of adult. Structurally, the cyst is lined by thin epithelium and shows a lumen usually filled with desquamated keratin, occasionally containing inflammatory cells. The nodes are formed as a result of cystic degeneration of epithelial rests of the dental lamina.