Medicare is an unofficial designation used to refer to the publicly funded single-payer healthcare system of Canada. Canada's health care system consists of 13 provincial and territorial health insurance plans, which provide universal healthcare coverage to Canadian citizens, permanent residents, and depending on the province or territory, certain temporary residents. The systems are individually administered on a provincial or territorial basis, within guidelines set by the federal government. The formal terminology for the insurance system is provided by the Canada Health Act and the health insurance legislation of the individual provinces and territories.

Health insurance or medical insurance is a type of insurance that covers the whole or a part of the risk of a person incurring medical expenses. As with other types of insurance, risk is shared among many individuals. By estimating the overall risk of health risk and health system expenses over the risk pool, an insurer can develop a routine finance structure, such as a monthly premium or payroll tax, to provide the money to pay for the health care benefits specified in the insurance agreement. The benefit is administered by a central organization, such as a government agency, private business, or not-for-profit entity.

A public hospital, or government hospital, is a hospital which is government owned and is fully funded by the government and operates solely off the money that is collected from taxpayers to fund healthcare initiatives. In almost all the developed countries but the United States of America, and in most of the developing countries, this type of hospital provides medical care free of charge to patients, covering expenses and wages by government reimbursement.

Uganda's health system is composed of health services delivered to the public sector, by private providers, and by traditional and complementary health practitioners. It also includes community-based health care and health promotion activities.

The Swedish health care system is mainly government-funded, universal for all citizens and decentralized, although private health care also exists. The health care system in Sweden is financed primarily through taxes levied by county councils and municipalities. A total of 21 councils are in charge with primary and hospital care within the country.

Germany has a universal multi-payer health care system paid for by a combination of statutory health insurance and private health insurance.

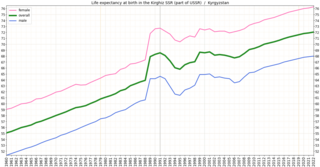

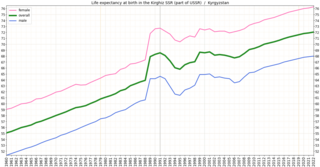

In the post-Soviet era, Kyrgyzstan's health system has suffered increasing shortages of health professionals and medicine. Kyrgyzstan must import nearly all its pharmaceuticals. The increasing role of private health services has supplemented the deteriorating state-supported system. In the early 2000s, public expenditures on health care decreased as a percentage of total expenditures, and the ratio of population to number of doctors increased substantially, from 296 per doctor in 1996 to 355 per doctor in 2001. A national primary-care health system, the Manas Program, was adopted in 1996 to restructure the Soviet system that Kyrgyzstan inherited. The number of people participating in this program has expanded gradually, and province-level family medicine training centers now retrain medical personnel. A mandatory medical insurance fund was established in 1997.

Healthcare in Turkey consists of a mix of public and private health services. Turkey introduced universal health care in 2003. Known as Universal Health Insurance Genel Sağlık Sigortası, it is funded by a tax surcharge on employers, currently at 5%. Public-sector funding covers approximately 75.2% of health expenditures.

In the post-Soviet era, the quality of Uzbekistan’s health care has declined. Between 1992 and 2003, spending on health care and the ratio of hospital beds to population both decreased by nearly 50 percent, and Russian emigration in that decade deprived the health system of many practitioners. In 2004 Uzbekistan had 53 hospital beds per 10,000 population. Basic medical supplies such as disposable needles, anesthetics, and antibiotics are in very short supply. Although all citizens nominally are entitled to free health care, in the post-Soviet era bribery has become a common way to bypass the slow and limited service of the state system. In the early 2000s, policy has focused on improving primary health care facilities and cutting the cost of inpatient facilities. The state budget for 2006 allotted 11.1 percent to health expenditures, compared with 10.9 percent in 2005.

As literacy and socioeconomic status improves in Ethiopia, the demand for quality service is also increasing. Besides, changes in the demographic trends, epidemiology and mushrooming urbanization require more comprehensive services covering a wide range and quality of curative, promotive and preventive services.

Kenya's health care system is structured in a step-wise manner so that complicated cases are referred to a higher level. Gaps in the system are filled by private and church run units.

The French health care system is one of universal health care largely financed by government national health insurance. In its 2000 assessment of world health care systems, the World Health Organization found that France provided the "best overall health care" in the world. In 2017, France spent 11.3% of GDP on health care, or US$5,370 per capita, a figure higher than the average spent by rich countries, though similar to Germany (10.6%) and Canada (10%), but much less than in the US. Approximately 77% of health expenditures are covered by government funded agencies.

In South Africa, private and public health systems exist in parallel. The public system serves the vast majority of the population. Authority and service delivery are divided between the national Department of Health, provincial health departments, and municipal health departments.

Healthcare in Georgia is provided by a universal health care system under which the state funds medical treatment in a mainly privatized system of medical facilities. In 2013, the enactment of a universal health care program triggered universal coverage of government-sponsored medical care of the population and improving access to health care services. Responsibility for purchasing publicly financed health services lies with the Social Service Agency (SSA).

Tanzania has a hierarchical health system which is in tandem with the political-administrative hierarchy. At the bottom, there are the dispensaries found in every village where the village leaders have a direct influence on its running. The health centers are found at ward level and the health center in charge is answerable to the ward leaders. At the district, there is a district hospital and at the regional level a regional referral hospital. The tertiary level is usually the zone hospitals and at a national level, there is the national hospital. There are also some specialized hospitals that do not fit directly into this hierarchy and therefore are directly linked to the ministry of health.

The Republic of Moldova has a universal health care system.

The nation of Austria has a two-tier health care system in which virtually all individuals receive publicly funded care, but they also have the option to purchase supplementary private health insurance. Care involving private insurance plans can include more flexible visiting hours and private rooms and doctors. Some individuals choose to completely pay for their care privately.

Examples of health care systems of the world, sorted by continent, are as follows.

The Health in Eswatini is poor and four years into the United Nations sustainable development goals, Eswatini seems unlikely to achieve goal on health. As a result of 63% poverty prevalence, 27% HIV prevalence, and poor health systems, maternal mortality rate is a high 389/100,000 live births, and under 5 mortality rate is 70.4/1000 live births resulting in a life expectancy that remains amongst the lowest in the world. Despite significant international aid, the government fails to adequately fund the health sector. Nurses are now and again engaged in demonstrations over poor working conditions, drug stock outs, all of which impairs quality health delivery. Despite tuberculosis and AIDS being major causes of death, diabetes and other non-communicable diseases are on the rise. Primary health care is relatively free in Eswatini save for its poor quality to meet the needs of the people. Road traffic accidents have increased over the years and they form a significant share of deaths in the country.