An abjad is a writing system in which only consonants are represented, leaving vowel sounds to be inferred by the reader. This contrasts with alphabets, which provide graphemes for both consonants and vowels. The term was introduced in 1990 by Peter T. Daniels. Other terms for the same concept include: partial phonemic script, segmentally linear defective phonographic script, consonantary, consonant writing, and consonantal alphabet.

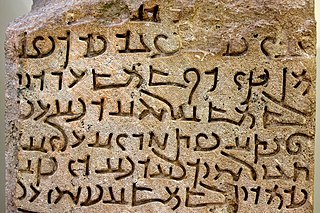

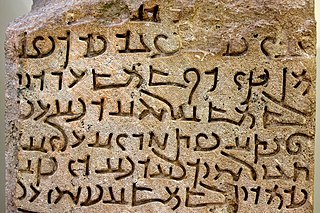

The ancient Aramaic alphabet was used to write the Aramaic languages spoken by ancient Aramean pre-Christian tribes throughout the Fertile Crescent. It was also adopted by other peoples as their own alphabet when empires and their subjects underwent linguistic Aramaization during a language shift for governing purposes — a precursor to Arabization centuries later — including among the Assyrians and Babylonians who permanently replaced their Akkadian language and its cuneiform script with Aramaic and its script, and among Jews, who adopted the Aramaic language as their vernacular and started using the Aramaic alphabet even for writing Hebrew, displacing the former Paleo-Hebrew alphabet.

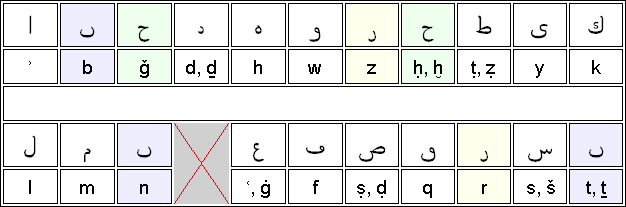

The Arabic alphabet, or Arabic abjad, is the Arabic script as specifically codified for writing the Arabic language. It is written from right-to-left in a cursive style, and includes 28 letters, of which most have contextual letterforms. The Arabic alphabet is considered an abjad, with only consonants required to be written; due to its optional use of diacritics to notate vowels, it is considered an impure abjad.

Aramaic is a Northwest Semitic language that originated in the ancient region of Syria and quickly spread to Mesopotamia, the southern Levant, southeastern Anatolia, Eastern Arabia and Sinai Peninsula, where it has been continually written and spoken in different varieties for over three thousand years.

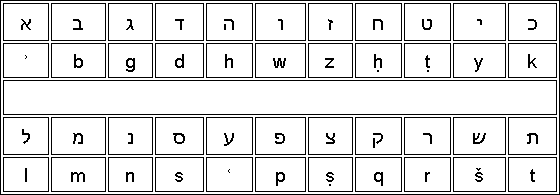

The Hebrew alphabet, known variously by scholars as the Ktav Ashuri, Jewish script, square script and block script, is traditionally an abjad script used in the writing of the Hebrew language and other Jewish languages, most notably Yiddish, Ladino, Judeo-Arabic, and Judeo-Persian. In modern Hebrew, vowels are increasingly introduced. It is also used informally in Israel to write Levantine Arabic, especially among Druze. It is an offshoot of the Imperial Aramaic alphabet, which flourished during the Achaemenid Empire and which itself derives from the Phoenician alphabet.

Matres lectionis are consonants that are used to indicate a vowel, primarily in the writing of Semitic languages such as Arabic, Hebrew and Syriac. The letters that do this in Hebrew are alephא, heה, vavו and yodי, and in Arabic, the matres lectionis are ʾalifا, wāwو and yāʾي. The 'yod and waw in particular are more often vowels than they are consonants.

The Phoenician alphabet is an alphabet known in modern times from the Canaanite and Aramaic inscriptions found across the Mediterranean region. The name comes from the Phoenician civilization.

The Syriac alphabet is a writing system primarily used to write the Syriac language since the 1st century AD. It is one of the Semitic abjads descending from the Aramaic alphabet through the Palmyrene alphabet, and shares similarities with the Phoenician, Hebrew, Arabic and Sogdian, the precursor and a direct ancestor of the traditional Mongolian scripts.

Classical Arabic or Quranic Arabic is the standardized literary form of Arabic used from the 7th century and throughout the Middle Ages, most notably in Umayyad and Abbasid literary texts such as poetry, elevated prose and oratory, and is also the liturgical language of Islam. Classical Arabic is, furthermore, the register of the Arabic language on which Modern Standard Arabic is based.

Aljamiado or Aljamía texts are manuscripts that use the Arabic script for transcribing European languages, especially Romance languages such as Old Spanish or Aragonese.

The Mandaic alphabet is a writing system primarily used to write the Mandaic language. It is thought to have evolved between the second and seventh century CE from either a cursive form of Aramaic or from Inscriptional Parthian. The exact roots of the script are difficult to determine. It was developed by members of the Mandaean faith of Lower Mesopotamia to write the Mandaic language for liturgical purposes. Classical Mandaic and its descendant Neo-Mandaic are still in limited use. The script has changed very little over centuries of use.

Western Neo-Aramaic, more commonly referred to as Siryon, is a modern Western Aramaic language. Today, it is spoken by Christian and Muslim Arameans (Syriacs) in only two villages – Maaloula and Jubb'adin, until the Syrian Civil War also in Bakhʽa – in the Anti-Lebanon Mountains of western Syria. Bakhʽa was completely destroyed during the war and all the survivors fled to other parts of Syria or to Lebanon. Western Neo-Aramaic is believed to be the closest living language to the language of Jesus, whose first language, according to scholarly consensus, was Galilean Aramaic belonging to the Western branch as well; all other remaining Neo-Aramaic languages are of the Eastern branch.

The Nabataean script is an abjad that was used to write Nabataean Aramaic and Nabataean Arabic from the second century BC onwards. Important inscriptions are found in Petra, the Sinai Peninsula, and other archaeological sites including Abdah and Mada'in Saleh in Saudi Arabia.

Aleph is the first letter of the Semitic abjads, including Phoenician ʾālep 𐤀, Hebrew ʾālef א, Aramaic ʾālap 𐡀, Syriac ʾālap̄ ܐ, Arabic ʾalif ا, and North Arabian 𐪑. It also appears as South Arabian 𐩱 and Ge'ez ʾälef አ.

The history of the alphabet goes back to the consonantal writing system used for Semitic languages in the Levant in the 2nd millennium BCE. Most or nearly all alphabetic scripts used throughout the world today ultimately go back to this Semitic proto-alphabet. Its first origins can be traced back to a Proto-Sinaitic script developed in Ancient Egypt to represent the language of Semitic-speaking workers and slaves in Egypt. Unskilled in the complex hieroglyphic system used to write the Egyptian language, which required a large number of pictograms, they selected a small number of those commonly seen in their Egyptian surroundings to describe the sounds, as opposed to the semantic values, of their own Canaanite language. This script was partly influenced by the older Egyptian hieratic, a cursive script related to Egyptian hieroglyphs. The Semitic alphabet became the ancestor of multiple writing systems across the Middle East, Europe, northern Africa, and Pakistan, mainly through Ancient South Arabian, Phoenician, Paleo-Hebrew and later Aramaic, four closely related members of the Semitic family of scripts that were in use during the early first millennium BCE.

The Ottoman Turkish alphabet is a version of the Perso-Arabic script used to write Ottoman Turkish until 1928, when it was replaced by the Latin-based modern Turkish alphabet.

The Arabic script is the writing system used for Arabic and several other languages of Asia and Africa. It is the second-most widely used alphabetic writing system in the world, the second-most widely used writing system in the world by number of countries using it, and the third-most by number of users.

Nabataean Aramaic is the extinct Aramaic variety used in inscriptions by the Nabataeans of the East Bank of the Jordan River, the Negev, and the Sinai Peninsula. Compared with other varieties of Aramaic, it is notable for the occurrence of a number of loanwords and grammatical borrowings from Arabic or other North Arabian languages.

Aramaic of Hatra, Hatran Aramaic or Ashurian designates a Middle Aramaic dialect, that was used in the region of Hatra and Assur in northeastern parts of Mesopotamia, approximately from the 3rd century BC to the 3rd century CE. Its range extended from the Nineveh Plains in the centre, up to Tur Abdin in the north, Dura-Europos in the west and Tikrit in the south.

Old Arabic is the name for any Arabic language or dialect continuum before Islam. Various forms of Old Arabic are attested in scripts like Safaitic, Hismaic, Nabatean, and even Greek.