Mandarin is a group of Chinese language dialects that are natively spoken across most of northern and southwestern China. The group includes the Beijing dialect, the basis of the phonology of Standard Chinese, the official language of China. Because Mandarin originated in North China and most Mandarin dialects are found in the north, the group is sometimes referred to as Northern Chinese. Many varieties of Mandarin, such as those of the Southwest and the Lower Yangtze, are not mutually intelligible with the standard language. Nevertheless, Mandarin as a group is often placed first in lists of languages by number of native speakers.

Hakka forms a language group of varieties of Chinese, spoken natively by the Hakka people in parts of Southern China and some diaspora areas of Taiwan, Southeast Asia and in overseas Chinese communities around the world.

Yue is a branch of the Sinitic languages primarily spoken in Southern China, particularly in the provinces of Guangdong and Guangxi.

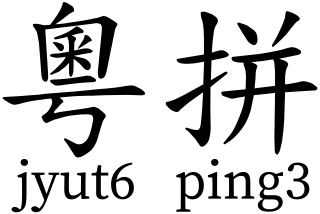

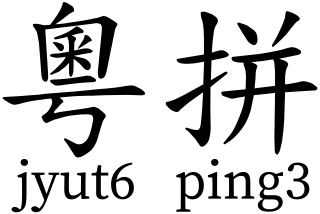

The Linguistic Society of Hong Kong Cantonese Romanization Scheme, also known as Jyutping, is a romanisation system for Cantonese developed in 1993 by the Linguistic Society of Hong Kong (LSHK).

The culture of Hong Kong is primarily a mix of Chinese and Western influences, stemming from Lingnan Cantonese roots and later fusing with British culture due to British colonialism. As an international financial center dubbed "Asia's World City", contemporary Hong Kong has also absorbed many international influences from around the world. Moreover, Hong Kong also has indigenous people and ethnic minorities from South and Southeast Asia, whose cultures all play integral parts in modern-day Hong Kong culture. As a result, after the 1997 transfer of sovereignty to the People's Republic of China, Hong Kong has continued to develop a unique identity under the rubric of One Country, Two Systems.

Macanese patois, known as patuá to its speakers, is a Portuguese-based creole language with a substrate from Cantonese, Malay and Sinhala, which was originally spoken by the Macanese community of the Portuguese colony of Macau. It is now spoken by a few families in Macau and in the Macanese diaspora.

Cantonese is a language within the Chinese (Sinitic) branch of the Sino-Tibetan languages originating from the city of Guangzhou and its surrounding Pearl River Delta. It is the traditional prestige variety of the Yue Chinese group, which has over 82.4 million native speakers. While the term Cantonese specifically refers to the prestige variety, it is often used to refer to the entire Yue subgroup of Chinese, including related but partially mutually intelligible varieties like Taishanese.

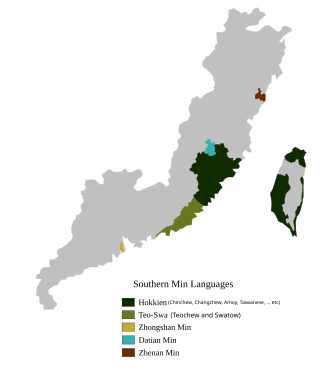

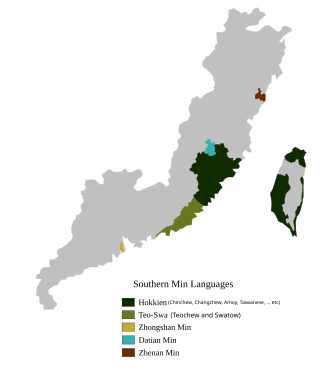

Teochew or Chaozhou, also called Teo-Swa or Chaoshan Chinese: 潮汕話, Teochew: Dio5suan3 uê7, Mandarin: Cháoshàn huà) is a Southern Min language spoken by the Teochew people in the Chaoshan region of eastern Guangdong and by their diaspora around the world. It is sometimes referred to as Chiuchow, its Cantonese rendering, due to English romanization by colonial officials and explorers. It is closely related to Hokkien, as it shares some cognates and phonology with Hokkien. The two are mutually unintelligible, but it is possible to understand some words.

The Hong Kong Government uses an unpublished system of Romanisation of Cantonese for public purposes which is based on the 1888 standard described by Roy T Cowles in 1914 as Standard Romanisation. The primary need for Romanisation of Cantonese by the Hong Kong Government is in the assigning of names to new streets and places. It has not formally or publicly disclosed its method for determining the appropriate Romanisation in any given instance.

Written Cantonese is the most complete written form of a Chinese language after that for Mandarin Chinese and Classical Chinese. Written Chinese was the main literary language of China until the 19th century. Written vernacular Chinese first appeared in the 17th century, and a written form of Mandarin became standard throughout China in the early 20th century. Cantonese is a common language in places like Hong Kong and Macau. While the Mandarin form can to some extent be read and spoken word for word in other Chinese varieties, its intelligibility to non-Mandarin speakers is poor to incomprehensible because of differences in idioms, grammar and usage. Modern Cantonese speakers have therefore developed new characters for words that do not exist and have retained others that have been lost in standard Chinese.

Starting in the 1980s, proper Cantonese pronunciation has been much promoted in Hong Kong, with the scholar Richard Ho (何文匯) as its iconic campaigner. The very idea of proper pronunciation of Cantonese is controversial, since the concept of labeling native speakers' usage and speech in terms of correctness is not generally supported by linguistics. Law et al. (2001) point out that the phrase 懶音 laan5 jam1 "lazy sounds," most commonly discussed in relation to phonetic changes in Hong Kong Cantonese, implies that the speaker is unwilling to put forth sufficient effort to articulate the standard pronunciation.

During the British colonial era, English was the sole official language until 1978. Today, the Basic Law of Hong Kong states that English and Chinese are the two official languages of Hong Kong. All roads and government signs are bilingual, and both languages are used in academia, business and the courts, as well as in most government materials today.

Cantonese is an analytic language in which the arrangement of words in a sentence is important to its meaning. A basic sentence is in the form of SVO, i.e. a subject is followed by a verb then by an object, though this order is often violated because Cantonese is a topic-prominent language. Unlike synthetic languages, seldom do words indicate time, gender and number by inflection. Instead, these concepts are expressed through adverbs, aspect markers, and particles, or are deduced from the context. Different particles are added to a sentence to further specify its status or intonation.

The five most common Cantonese profanities, vulgar words in the Cantonese language are diu (屌/𨳒), gau (鳩/㞗/𨳊), lan (撚/𨶙), tsat (柒/杘/𨳍) and hai (屄/閪), where the first ("diu") literally means fuck, "hai" is a word for female genitalia and "gau" refers to male genitalia. They are sometimes collectively known as the "outstanding five in Cantonese" (廣東話一門五傑). These five words are generally offensive and give rise to a variety of euphemisms and minced oaths. Similar to the seven dirty words in the United States, these five words are forbidden to say and are bleep-censored on Hong Kong broadcast television. Other curse phrases, such as puk gai (仆街/踣街) and ham gaa caan (冚家鏟/咸家鏟), are also common.

Code-switching is a type of linguistic behaviour that juxtaposes "passages of speech belonging to two different grammatical systems or sub-systems, within the same exchange". Code-switching in Hong Kong mainly concerns two grammatical systems: Cantonese and English. According to Matrix Language Frame Model, Cantonese, as the "matrix language", contributes bound morphemes, content and function words, whereas, English, the "embedded language", contributes lexical, phrases or compound words.

Standard Cantonese pronunciation is that of Guangzhou, also known as Canton, capital of Guangdong Province. Hong Kong Cantonese is related to Guangzhou dialect, and they diverge only slightly. Yue dialects in other parts of Guangdong and Guangxi provinces like Taishanese, may be considered divergent to a greater degree.

Slang in Hong Kong evolves over time, and mainly comprises Cantonese, English, or a combination of the two.

Cantonese Internet Slang is an informal language originating from Internet forums, chat rooms, and other social platforms. It is often adapted with self-created and out-of-tradition forms. Cantonese Internet Slang is prevalent among young Cantonese speakers and offers a reflection of the youth culture of Hong Kong.

Malaysian Cantonese is a local variety of Cantonese spoken in Malaysia. It is the lingua franca among Chinese throughout much of the central portion of Peninsular Malaysia, being spoken in the capital Kuala Lumpur, Perak, Pahang, Selangor and Negeri Sembilan, it is also widely understood to varying degrees by many Chinese throughout the country, regardless of their ancestral language.