|

|---|

Human rights in Rwanda have been violated on a grand scale. The greatest violation is the Rwandan genocide of Tutsi in 1994. The post-genocide government is also responsible for grave violations of human rights.

|

|---|

Human rights in Rwanda have been violated on a grand scale. The greatest violation is the Rwandan genocide of Tutsi in 1994. The post-genocide government is also responsible for grave violations of human rights.

As decolonization ideas spread across Africa, a Tutsi party and Hutu party were created. Both became militarized, and in 1959, Tutsi attempted to assassinate Grégoire Kayibanda, the leader of PARMEHUTU. This resulted in the wind of destruction known as the "Social Revolution" in Rwanda, violence which pitted Hutu against Tutsi, killing 20,000 to 100,000 Tutsi and forcing more into exile.

After the withdrawal of Belgium from Africa in 1962, Rwanda separated from Rwanda-Urundi by referendum, which also eliminated the Tutsi monarchy, the mwami. In 1963, the Hutu government killed 14,000 Tutsi, after Tutsi guerillas attacked Rwanda from Burundi. The government maintained mandatory ethnic identity cards, and capped Tutsi numbers in universities and the civil service.[ citation needed ]

During the genocide against the Tutsi in 1994, about 800,000 Tutsi people were slaughtered. [1]

Subsequent governments, including the current government led by President Paul Kagame, have committed grave violations of human rights. [2]

On 22 April 1995 the Rwandan Patriotic Army killed more than 4,000 people in the Kibeho massacre. [3]

In September 1996 Rwanda invaded Zaire, precipitating the First Congo War. The immediate targets of the invasion were the large Hutu refugee camps located right across the border in the vicinity of Goma and Bukavu, which were organized under the leadership of the former regime. [4] The Rwandan army chased the refugees in hot pursuit clear across Zaire, while helping to install AFDL in power in Kinshasa. The historian Gérard Prunier estimated the death toll among the fleeing refugees to lay between 213,000–280,000. [5]

In 2010, the United Nations issued a report investigating 617 alleged violent incidents occurring in the Democratic Republic of Congo between March 1993 and June 2003. [6] It reported that the "apparent systematic and widespread attacks described in this report reveal a number of inculpatory elements that, if proven before a competent court, could be characterized as crimes of genocide" against Hutus. The report was categorically rejected by the Rwandan government. [7]

In December 1996 the Rwandan government launched a forced villagization program which sought to concentrate the entire rural population in villages known as Imidugudu , [8] which resulted in human rights violations of tens of thousands of Rwandans, according to Human Rights Watch. [9]

According to a report by Amnesty International, between December 1997 and May 1998, thousands of Rwandans "disappeared" or were murdered by members of government security forces and of armed opposition groups. Most of the killings took place in Rwanda's northwestern provinces of Gisenyi and Ruhengeri where there was an armed insurgency. Amnesty wrote that "Thousands of unarmed civilians have been extrajudicially executed by RPA soldiers in the context of military search operations in the northwest." [10]

When Kagame visited Washington in early 2001, Human Rights Watch criticized Rwanda for its involvement in the Second Congo War in which "as many as 1.7 million" civilians had died. [11]

Regarding human rights under the government of President Paul Kagame, Human Rights Watch in 2007 accused Rwandan police of several instances of extrajudicial killings and deaths in custody. [12] [13] In June 2006, the International Federation of Human Rights and Human Rights Watch described what they called "serious violations of international humanitarian law committed by the Rwanda Patriotic Army". [14]

According to The Economist in 2008, Kagame "allows less political space and press freedom at home than Robert Mugabe does in Zimbabwe", and "[a]nyone who poses the slightest political threat to the regime is dealt with ruthlessly". [15]

Kagame has been accused of using memories of the genocide to muzzle his opposition. In 2009, Human Rights Watch claimed that under the pretense of maintaining ethnic harmony, Kagame's government displays "a marked intolerance of the most basic forms of dissent." It also claimed that laws enacted in 2009 that ban "genocide ideology" are frequently used to legally gag the opposition. [16] In 2010, along similar lines, The Economist claimed that Kagame frequently accuses his opponents of "divisionism," or fomenting racial hatred. [17] In 2011, Freedom House noted that the government justifies restrictions on civil liberties as a necessary measure to prevent ethnic violence. These restrictions are so severe that even mundane discussions of ethnicity can result in being arrested for divisionism. [18]

The United States government in 2006 described the human rights record of the Kagame government as "mediocre", citing the "disappearances" of political dissidents, as well as arbitrary arrests and acts of violence, torture, and murders committed by police. U. S. authorities listed human rights problems including the existence of political prisoners and limited freedom of the press, freedom of assembly and freedom of religion. [19]

Reporters Without Borders listed Rwanda in 147th place out of 169 for freedom of the press in 2007, [20] and reported that "Rwandan journalists suffer permanent hostility from their government and surveillance by the security services". It cited cases of journalists being threatened, harassed, and arrested for criticising the government. According to Reporters Without Borders, "President Paul Kagame and his government have never accepted that the press should be guaranteed genuine freedom". [21]

In 2010, Rwanda fell to 169th place, out of 178, entering the ranks of the ten lowest-ranked countries in the world for press freedom. Reporters Without Borders stated that "Rwanda, Yemen and Syria have joined Burma and North Korea as the most repressive countries in the world against journalists", [22] adding that in Rwanda, "the third lowest-ranked African country", "this drop was caused by the suspending of the main independent press media, the climate of terror surrounding the presidential election, and the murdering, in Kigali, of the deputy editor of Umuvugizi , Jean-Léonard Rugambage. In proportions almost similar to those of Somalia, Rwanda is emptying itself of its journalists, who are fleeing the country due to their fear of repression". [23]

In December 2008, a draft report commissioned by the United Nations, to be presented to the Sanctions Committee of the United Nations Security Council, alleged that Kagame's Rwanda was supplying child soldiers to Tutsi rebels in Nord-Kivu, Democratic Republic of the Congo, in the context of the conflict in Nord-Kivu in 2008. The report also alleged that Rwanda was supplying General Laurent Nkunda with "military equipment, the use of Rwandan banks, and allow[ing] the rebels to launch attacks from Rwandan territory on the Congolese army". [24]

In July 2009, the Commonwealth Human Rights Initiative issued a report critical of the human rights situation in Rwanda. [25] It highlighted "a lack of political freedom and harassment of journalists". [26] It urged the Rwandan government to enact legislation enabling freedom of information and to "authorise the presence of an opposition in the next election". [27] It also emphasised abuses carried out by Rwandan troops in the Democratic Republic of the Congo, and described Rwanda's overall human rights situation as "very poor": [28]

The report details a country in which democracy, freedom of speech, the press and human rights are undermined or violently abused, in which courts fail to meet international standards, and a country which has invaded its neighbour, the Democratic Republic of Congo, four times since 1994. ... Censorship is prevalent, according to the report, and the government has a record of shutting down independent media and harassing journalists. It concludes that Rwanda's constitution is used as a "façade" to hide "the repressive nature of the regime" and backs claims that Rwanda is essentially "an army with a state". [29]

In the lead-up to the 2010 presidential election, the United Nations "demanded a full investigation into allegations of politically motivated killings of opposition figures". André Kagwa Rwisereka, the president of the Democratic Green Party of Rwanda, was found beheaded. "[A] lawyer who had participated in genocide trials at a UN tribunal was shot dead". There was a murder attempt on Kayumba Nyamwasa, "a former senior Rwandan general who had fallen out with Kagame". And Jean-Léonard Rugambage, a journalist investigating that attempted murder, was himself murdered. [30] [31]

In 2011, Amnesty International criticized the continued detention of former transportation minister and Bizimungu ally Charles Ntakirutinka, who was seven years into a ten-year sentence at Kigali central prison. [32] Amnesty International called him a prisoner of conscience and named him a 2011 "priority case". [32]

In October 2012, the body of Théogène Turatsinze, a Rwandan businessman living in Mozambique, who was thought to have "had access to politically sensitive financial information related to certain Rwandan government insiders", was found tied up and floating in the sea. Police in Mozambique "initially indicated Rwandan government involvement in the killing before contacting the government and changing its characterization to a common crime. Rwandan government officials publicly condemned the killing and denied involvement." [33] Foreign media connected the murder to those of several prominent critics of the Rwandan government over the previous two years. [34] [35]

To improve the perception of its human rights record, the Rwandan government in 2009 engaged a U. S. public relations firm, Racepoint Group, who had improved the image of Libya's Gaddafi, Tunisia, Angola, Equatorial Guinea, Ethiopia, and Senegal. An internet site was set up by BTP advisers, a British firm, to attack critics. Racepoint's agreement with the government stated that it would "flood" the Internet and the media with positive stories about Rwanda. [36]

In 2020, regime critic Paul Rusesabagina who had fled the country and become a Belgian citizen, was tricked into boarding a private flight to Rwanda, arrested, and the next year sentenced to 25 years in prison on charges that human rights advocates called politically motivated.

The following chart shows Rwanda's ratings since 1972 in the Freedom in the World reports, published annually by Freedom House. A rating of 1 is "free"; 7, "not free". [43] 1

| Historical ratings | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Rwanda's stances on international human rights treaties are as follows:

On 26 July 2022, chairman of the US Senate Foreign Relations Committee raised concerns about the Rwandan government's human rights record and role in the conflict in the Democratic Republic of Congo. In a letter to US Secretary of State Antony Blinken, Senator Robert Menendez called for a comprehensive review of US policy towards Rwanda. [64]

Rwanda, officially the Republic of Rwanda, is a landlocked country in the Great Rift Valley of Central Africa, where the African Great Lakes region and Southeast Africa converge. Located a few degrees south of the Equator, Rwanda is bordered by Uganda, Tanzania, Burundi, and the Democratic Republic of the Congo. It is highly elevated, giving it the soubriquet "land of a thousand hills", with its geography dominated by mountains in the west and savanna to the southeast, with numerous lakes throughout the country. The climate is temperate to subtropical, with two rainy seasons and two dry seasons each year. It is the most densely populated mainland African country; among countries larger than 10,000 km2, it is the fifth most densely populated country in the world. Its capital and largest city is Kigali.

Human occupation of Rwanda is thought to have begun shortly after the last ice age. By the 11th century, the inhabitants had organized into a number of kingdoms. In the 19th century, Mwami (king) Rwabugiri of the Kingdom of Rwanda conducted a decades-long process of military conquest and administrative consolidation that resulted in the kingdom coming to control most of what is now Rwanda. The colonial powers, Germany and Belgium, allied with the Rwandan court.

The International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda was an international court established in November 1994 by the United Nations Security Council in Resolution 955 in order to adjudicate people charged for the Rwandan genocide and other serious violations of international law in Rwanda, or by Rwandan citizens in nearby states, between 1 January and 31 December 1994. The court eventually convicted 61 individuals and acquitted 14.

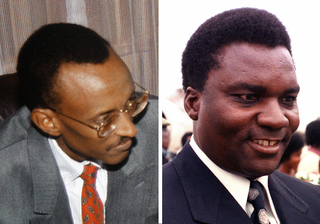

Juvénal Habyarimana was a Rwandan politician and military officer who served as the second president of Rwanda, from 1973 until his assassination in 1994. He was nicknamed Kinani, a Kinyarwanda word meaning "invincible".

Paul Kagame is a Rwandan politician and former military officer who has been the fourth President of Rwanda since 2000. He was previously a commander of the Rwandan Patriotic Front (RPF), a rebel armed force which invaded Rwanda in 1990. The RPF was one of the parties of the conflict during the Rwandan Civil War and the armed force which ended the Rwandan genocide. He was considered Rwanda's de facto leader when he was Vice President and Minister of Defence under President Pasteur Bizimungu from 1994 to 2000 after which the vice-presidential post was abolished.

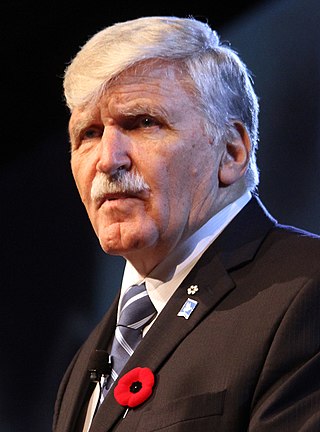

Roméo Antonius Dallaire is a retired Canadian politician and military officer who was a senator from Quebec from 2005 to 2014, and a lieutenant-general in the Canadian Armed Forces. He notably was the force commander of UNAMIR, the ill-fated United Nations peacekeeping force for Rwanda between 1993 and 1994, and for trying to stop the genocide that was being waged by Hutu extremists against Tutsis. Dallaire is a Senior Fellow at the Montreal Institute for Genocide and Human Rights Studies (MIGS) and co-director of the MIGS Will to Intervene Project.

The Rwandan Patriotic Front, is the ruling political party in Rwanda.

The Interahamwe is a Hutu paramilitary organization active in the Democratic Republic of the Congo and Uganda. The Interahamwe was formed around 1990 as the youth wing of the National Republican Movement for Democracy and Development, the then-ruling party of Rwanda, and enjoyed the backing of the Hutu Power government. The Interahamwe, led by Robert Kajuga, were the main perpetrators of the Rwandan genocide, during which an estimated 500,000 to 1,000,000 Tutsi, Twa, and moderate Hutus were killed from April to July 1994, and the term "Interahamwe" was widened to mean any civilian militias or bands killing Tutsi.

The Rwandan genocide, also known as the genocide against the Tutsi, occurred between 7 April and 19 July 1994 during the Rwandan Civil War. During this period of around 100 days, members of the Tutsi minority ethnic group, as well as some moderate Hutu and Twa, were killed by armed Hutu militias. Although the Constitution of Rwanda states that more than 1 million people perished in the genocide, the actual number of fatalities is unclear, and some estimates suggest that the real number killed was likely lower. The most widely accepted scholarly estimates are around 500,000 to 800,000 Tutsi deaths.

The First Congo War (1996–1997), also nicknamed Africa's First World War, was a civil war and international military conflict which took place mostly in Zaire, with major spillovers into Sudan and Uganda. The conflict culminated in a foreign invasion that replaced Zairean president Mobutu Sese Seko with the rebel leader Laurent-Désiré Kabila. Kabila's unstable government subsequently came into conflict with his allies, setting the stage for the Second Congo War in 1998–2003.

The failure of the international community to effectively respond to the Rwandan genocide of 1994 has been the subject of significant criticism. During a period of around 100 days, between 7 April and 15 July, an estimated 500,000-1,100,000 Rwandans, mostly Tutsi and moderate Hutu, were murdered by Interahamwe militias.

The Rwandan Civil War was a large-scale civil war in Rwanda which was fought between the Rwandan Armed Forces, representing the country's government, and the rebel Rwandan Patriotic Front (RPF) from 1 October 1990 to 18 July 1994. The war arose from the long-running dispute between the Hutu and Tutsi groups within the Rwandan population. A 1959–1962 revolution had replaced the Tutsi monarchy with a Hutu-led republic, forcing more than 336,000 Tutsi to seek refuge in neighbouring countries. A group of these refugees in Uganda founded the RPF which, under the leadership of Fred Rwigyema and Paul Kagame, became a battle-ready army by the late 1980s.

Christianity is the largest religion in Rwanda. The most recent national census from 2012 indicates that: 43.7% of Rwanda's population is Catholic, 37.7% is Protestant, 11.8% is Seventh-day Adventist, 2.0% is Muslim, 2.5% claims no religious affiliation, and 0.7% is Jehovah's Witness.

Seth Sendashonga was the Minister of the Interior in the government of national unity in Rwanda, following the military victory of the Rwandan Patriotic Front (RPF) after the 1994 genocide. One of the politically moderate Hutus in the National Unity Cabinet, he became increasingly disenchanted with the RPF and was eventually forced from office in 1995 after criticizing government policies. After surviving a 1996 assassination attempt while in exile in Kenya, he launched a new opposition movement, the Forces de Résistance pour la Démocratie (FRD). Sendashonga was killed by unidentified gunmen in May 1998. The Rwandan government is widely believed to be responsible for the assassination.

These are some of the articles related to Rwanda on the English Wikipedia pages:

The Republic of Congo gained independence from French Equatorial Africa in 1960. It was a one-party Marxist–Leninist state from 1969 to 1991. Multi-party elections have been held since 1992, although a democratically elected government was ousted in the 1997 civil war and President Denis Sassou Nguesso has ruled for 26 of the past 36 years. The political stability and development of hydrocarbon production made the Republic of the Congo the fourth largest oil producer in the Gulf of Guinea region, providing the country with relative prosperity despite instability in some areas and unequal distribution of oil revenue nationwide.

The Congolese Human Right Observatory claims a number of unresolved and pending issues in the country.

Discrimination against Pygmies is widespread, the result of cultural biases, especially traditional relationships with the Bantu, as well as more contemporary forms of exploitation.

Human rights in Cameroon are addressed in the constitution. However, the 2009 Human Rights Report by the United States Department of State noted concerns in regard to election irregularities, security forces torture and arbitrary arrests.

In 2022, Freedom House rated Burundi's human rights at 14 out 100.

Equatorial Guinea is known for human rights abuses. Under the current government it has "limited ability of citizens to change their government; increased reports of unlawful murders of civilians by security forces; government-sanctioned kidnappings; systematic torture of prisoners and detainees by security forces; life threatening conditions in prisons and detention facilities; impunity; arbitrary arrest and detention and incommunicado detention; harassment and deportation of foreign residents with limited due process; judicial corruption and lack of due process; restrictions on the right to privacy; restrictions on freedom of speech and of the press; restrictions on the rights of assembly, association, and movement; government corruption; violence and discrimination against women; suspected trafficking in persons; discrimination against ethnic minorities; and restrictions on labor rights."

In Praise of Blood: The Crimes of the Rwandan Patriotic Front is a 2018 non-fiction book by Canadian journalist Judi Rever and published by Random House of Canada; it has also been translated into Dutch and French. The book describes alleged war crimes by the Rwandan Patriotic Front (RPF), Rwanda's ruling political party, during its ascent to power in the 1990s.