Chicano or Chicana is an ethnic identity for Mexican Americans who have a non-Anglo self-image, embracing their Mexican Native ancestry. Chicano was originally a classist and racist slur used toward low-income Mexicans that was reclaimed in the 1940s among youth who belonged to the Pachuco and Pachuca subculture. In the 1960s, Chicano was widely reclaimed in the building of a movement toward political empowerment, ethnic solidarity, and pride in being of indigenous descent. Chicano developed its own meaning separate from Mexican American identity. Youth in barrios rejected cultural assimilation into whiteness and embraced their own identity and worldview as a form of empowerment and resistance. The community forged an independent political and cultural movement, sometimes working alongside the Black power movement.

Ethnic studies, in the United States, is the interdisciplinary study of difference—chiefly race, ethnicity, and nation, but also sexuality, gender, and other such markings—and power, as expressed by the state, by civil society, and by individuals.

John Huppenthal is an American politician who served as Arizona Superintendent of Public Instruction from 2011 to 2015. Prior to being elected Superintendent, Huppenthal served as City Councilman, State Representative, and State Senator. Huppenthal was also a Senior Planning Analyst for Salt River Project.

Latino studies is an academic discipline which studies the experience of people of Latin American ancestry in the United States. Closely related to other ethnic studies disciplines such as African-American studies, Asian American studies, and Native American studies, Latino studies critically examines the history, culture, politics, issues, sociology, spirituality (Indigenous) and experiences of Latino people. Drawing from numerous disciplines such as sociology, history, literature, political science, religious studies and gender studies, Latino studies scholars consider a variety of perspectives and employ diverse analytical tools in their work.

Luis Miguel Valdez is an American playwright, screenwriter, film director and actor. Regarded as the father of Chicano film and playwriting, Valdez is best known for his play Zoot Suit, his movie La Bamba, and his creation of El Teatro Campesino. A pioneer in the Chicano Movement, Valdez broadened the scope of theatre and arts of the Chicano community.

Tucson Unified School District (TUSD) is the largest school district of Tucson, Arizona, in terms of enrollment. Dr. Gabriel Trujillo is the superintendent, appointed on September 12, 2017, by the Governing Board. As of 2016, TUSD had more than 47,670 students. As of Fall 2012, according to Superintendent John Pedicone, TUSD had 50,000 students. District enrollment has declined over the last 10 years and TUSD lost 1,700 to 2,000 students per year for the two or three years prior to 2012.

Chicano/a studies, also known as Chican@ studies, originates from the Chicano Movement of the late 1960s and 1970s, and is the study of the Chicana/o and Latina/o experience. Chican@ studies draws upon a variety of fields, including history, sociology, the arts, and Chican@ literature. The area of studies additionally emphasizes the importance of Chican@ educational materials taught by Chican@ educators for Chican@ students.

Catalina High School is a public high school, located on the north side of Tucson, Arizona, United States. Catalina is a magnet high school in Tucson Unified School District and serves approximately 750 students in grades 9-12. The school name originates from the Santa Catalina Mountains north of Tucson. The school mascot is the Trojan, and the school colors are royal blue and white.

Tucson High Magnet School, commonly referred to as THMS, THS, or Tucson High, is a public high school in Tucson, Arizona. It is part of the Tucson Unified School District with magnet programs in Technology, Visual Arts, and Performing Arts. The school is located adjacent to the University of Arizona and is close to the Downtown Arts District. It is the oldest high school in Arizona, having been established in 1892 and then re-established in 1906. The school celebrated its centennial in 2006. In terms of enrollment, THMS is the largest high school in southern Arizona and the eleventh-largest in Arizona, with more than 3,200 students enrolled.

Mexican American literature is literature written by Mexican Americans in the United States. Although its origins can be traced back to the sixteenth century, the bulk of Mexican American literature dates from post-1848 and the United States annexation of large parts of Mexico in the wake of the Mexican–American War. Today, as a part of American literature in general, this genre includes a vibrant and diverse set of narratives, prompting critics to describe it as providing "a new awareness of the historical and cultural independence of both northern and southern American hemispheres". Chicano literature is an aspect of Mexican American literature.

Miguel Méndez was the pen name for Miguel Méndez Morales, a Mexican American author best known for his novel Peregrinos de Aztlán. He was a leading figure in the field of Chicano literature.

Cholla High School is a public high school, located on the West Side of Tucson, Arizona, United States. Cholla is a magnet high school in the Tucson Unified School District and serves over 1,700, students, grades 9–12. The school name originates from the cholla cactus, which is prominent throughout Tucson and Arizona. The school mascot is the Charger and the school colors are orange and blue.

Borderlands/La Frontera: The New Mestiza is a 1987 semi-autobiographical work by Gloria E. Anzaldúa that examines the Chicano and Latino experience through the lens of issues such as gender, identity, race, and colonialism. Borderlands is considered to be Anzaldúa’s most well-known work and a pioneering piece of Chicana literature.

Mexican WhiteBoy is a 2008 novel by Matt de la Peña, published by Delacorte Press. De la Peña drew on his own adolescent passion for sports in developing his main character Danny, a baseball enthusiast. The novel, which is set in National City, California, uses Spanglish and has a bicultural theme.

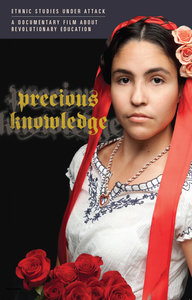

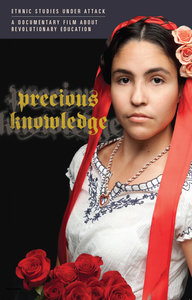

Precious Knowledge is a 2011 educational and political documentary that centers on the banning of the Mexican-American Studies (MAS) Program in the Tucson Unified School District of Arizona. The documentary was directed by Ari Luis Palos and produced by Eren Isabel McGinnis, the founders of Dos Vatos Productions.

Librotraficante was an American protest movement. It began in response to a 2012 decision by the Arizona Superintendent for Public Instruction calling for the removal of books from classes that "promote the overthrow of the United States government, foster racial and class-based resentment, favor one ethnic group over another, or advocate ethnic solidarity". Protesters organized a caravan which transported more than 1,000 banned books into Arizona. The caravan was relaunched in 2017 to coincide with a hearing about ethnic-studies courses in the Arizona Supreme Court. The protest received the Robert B. Downs Intellectual Freedom Award at the American Library Association's Midwinter meeting in 2013.

Xicanx is an English-language gender-neutral neologism and identity referring to people of Mexican descent in the United States. The ⟨-x⟩ suffix replaces the ⟨-o/-a⟩ ending of Chicano and Chicana that are typical of grammatical gender in Spanish. The term references a connection to Indigeneity, decolonial consciousness, inclusion of genders outside the Western gender binary imposed through colonialism, and transnationality. In contrast, most Latinos tend to define themselves in nationalist terms, such as by a Latin American country of origin.

Mary Romero is an American sociologist. She is Professor of Justice Studies and Social Inquiry at Arizona State University, with affiliations in African and African American Studies, Women and Gender Studies, and Asian Pacific American Studies. Before her arrival at ASU in 1995, she taught at University of Oregon, San Francisco State University, and University of Wisconsin-Parkside. Professor Romero holds a bachelor's degree in sociology with a minor in Spanish from Regis College in Denver, Colorado. She holds a PhD in sociology from the University of Colorado. In 2019, she served as the 110th President of the American Sociological Association.

Roberto Cintli Rodríguez was a Mexican-American journalist, columnist, poet, author, and academic of Mexican American Studies at the University of Arizona.

Pensamiento Serpentino is a poem by Chicano playwright Luis Valdez originally published by Cucaracha Publications, which was part of El Teatro Campesino, in 1973. The poem famously draws on philosophical concepts held by the Mayan people known as In Lak'ech, meaning "you are the other me." The poem also draws, although less prominently, on Aztec traditions, such as through the appearance of Quetzalcoatl. The poem received national attention after it was illegally banned as part of the removal of Mexican American Studies Programs in Tucson Unified School District. The ban was later ruled unconstitutional.