Chicano or Chicana is an ethnic identity for Mexican Americans who have a non-Anglo self-image, embracing their Mexican Native ancestry. Chicano was originally a classist and racist slur used toward low-income Mexicans that was reclaimed in the 1940s among youth who belonged to the Pachuco and Pachuca subculture. In the 1960s, Chicano was widely reclaimed in the building of a movement toward political empowerment, ethnic solidarity, and pride in being of indigenous descent. Chicano developed its own meaning separate from Mexican American identity. Youth in barrios rejected cultural assimilation into the mainstream American culture and embraced their own identity and worldview as a form of empowerment and resistance. The community forged an independent political and cultural movement, sometimes working alongside the Black power movement.

A zoot suit is a men's suit with high-waisted, wide-legged, tight-cuffed, pegged trousers, and a long coat with wide lapels and wide padded shoulders. It is most notable for its use as a cultural symbol among the Hepcat and Pachuco subcultures. Originating among African Americans it would later become popular with Mexican, Filipino, Italian, and Japanese Americans in the 1940s.

Pachucos are male members of a counterculture that emerged in El Paso, Texas, in the late 1930s. Pachucos are associated with zoot suit fashion, jump blues, jazz and swing music, a distinct dialect known as caló, and self-empowerment in rejecting assimilation into Anglo-American society. The pachuco counterculture flourished among Chicano boys and men in the 1940s as a symbol of rebellion, especially in Los Angeles. It spread to women who became known as pachucas and were perceived as unruly, masculine, and un-American. Some pachucos adopted strong attitudes of social defiance, engaging in behavior seen as deviant by white/Anglo-American society, such as marijuana smoking, gang activity, and a turbulent night life. Although concentrated among a relatively small group of Mexican Americans, the pachuco counterculture became iconic among Chicanos and a predecessor for the cholo subculture which emerged among Chicano youth in the 1980s.

Zoot Suit is a play written by Luis Valdez, featuring incidental music by Daniel Valdez and Lalo Guerrero. Zoot Suit is based on the Sleepy Lagoon murder trial and the Zoot Suit Riots. Debuting in 1979, Zoot Suit was the first Chicano play on Broadway. In 1981, Luis Valdez also directed a filmed version of the play, combining stage and film techniques.

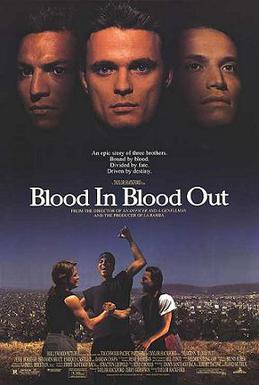

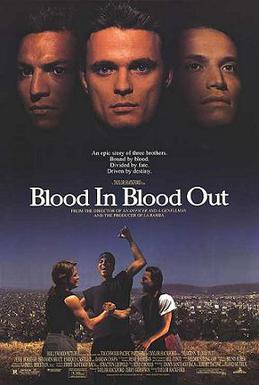

Blood In Blood Out is a 1993 American epic crime drama film directed by Taylor Hackford that has become a cult-classic film among the Mexican-American community. It follows the intertwining lives of three Chicano relatives from 1972 to 1984. They start out as members of a street gang in East Los Angeles, and as dramatic incidents occur, their lives and friendships are forever changed. Blood In Blood Out was filmed in 1991 throughout Los Angeles and inside California's San Quentin State Prison.

Jimmy Santiago Baca is an American poet, memoirist, and screenwriter from New Mexico.

Chicano poetry is a subgenre of Chicano literature that stems from the cultural consciousness developed in the Chicano Movement. Chicano poetry has its roots in the reclamation of Chicana/o as an identity of empowerment rather than denigration. As a literary field, Chicano poetry emerged in the 1960s and formed its own independent literary current and voice.

Luis Talamantez is an American writer, poet, and prisoner's rights activist. He gained widespread recognition in the 1970s as a member of the San Quentin Six, a group of men charged with inciting the riot which killed three guards and three inmates, including George Jackson. Talamantez published his poetry while incarcerated and is perhaps best known for his collection of poetry, titled Life Within the Heart Imprisoned.

Paños are pen or pencil drawings on fabric, a form of prison artwork made in the Southwest United States created primarily by pintos, or Chicanos who are or have been incarcerated.

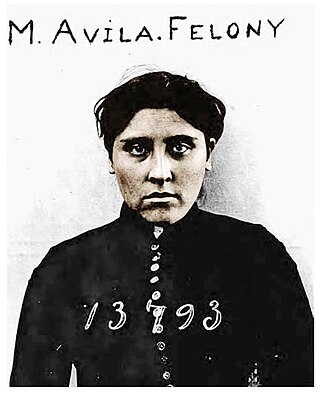

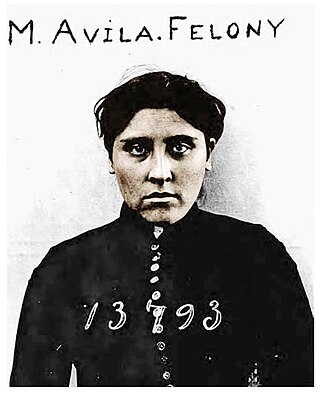

Modesta Ávila was a Californio ranchera and protester, best known for being the first convicted felon and first state prisoner in Orange County, California. Ávila had only received a minor warning in 1889 for placing an obstruction on the tracks to protest against the Santa Fe Railroad being built through her property without adequate compensation, but she continued to taunt the authorities, and was eventually arrested four months later.

Judy A. Lucero was a Chicana prisoner poet, cited as a legend among Latina feminists. Lucero had a particularly tough life, becoming a heroin addict after being introduced to drugs at the age of eleven by one of her stepfathers, losing two children and dying in prison at the age of 28 from a brain hemorrhage.

Shizu Saldamando, is an American visual artist. Her work merges painting and collage in portraits that often deal with social constructs of identity and subcultures. Saldamando also works in video, installation and performance art. She has been featured in numerous exhibitions, has attained accolades like that of Wanlass Artist in Residence, and is a successful writer, tattoo artist, and social activist.

"I Am Offering This Poem" is a poem by Jimmy Santiago Baca, first published in Immigrants in Our Own Land (1979). It was reprinted in 1990 in the collection Immigrants in Our Own Land and Selected Early Poems. Baca’s diction and imagery convey a central theme of the work- the importance of poetry and art in general.

A cholo or chola is a member of a Chicano and Latino subculture or lifestyle associated with a particular set of dress, behavior, and worldview which originated in Los Angeles. A veterano or veterana is an older member of the same subculture. Other terms referring to male members of the subculture may include vato and vato loco. Cholo was first reclaimed by Chicano youth in the 1960s and emerged as a popular identification in the late 1970s. The subculture has historical roots in the Pachuco subculture, but today is largely equated with anti-social behavior, criminal behavior and gang activity.

A Mexican American is a resident of the United States who is of Mexican descent. Mexican American-related topics include the following:

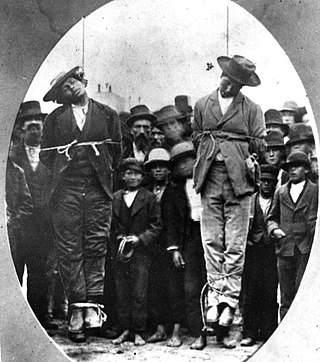

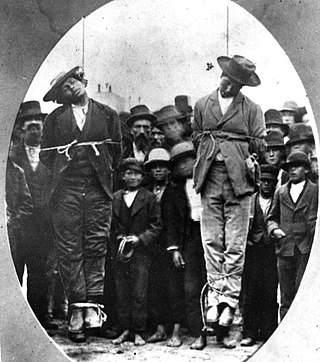

Gringo justice is a sociohistorical critical theory developed by Chicano sociologist, lawyer, and activist Alfredo Mirandé in 1987, who used it to provide an alternative explanation for Chicano criminality in the United States and challenge the racist assumption that Chicanos were inherently criminal, or biologically, psychologically, or culturally predisposed to engage in criminal behavior. The theory is applied by Chicano and Latino scholars to explain the double standard of justice in the criminal justice system between Anglo-Americans and Chicanos/Latinos. The theory also challenges stereotypes of Chicanos/Latinos as "bandidos," "gang-bangers," and "illegal alien drug smugglers," which have historically developed and are maintained to justify social control over Chicano/Latino people in the US.

Raúl R. Salinas, better known by his pen name raúlrsalinas, was a Chicano pinto poet, memoirist, social activist, and prison journalist. Much of raúlrsalinas' writing was grounded in arguments for social justice and human rights. He was an early pioneer of Chicano pinto (prisoner) poetry and is notable for his use of vernacular, bilingual, and free verse aesthetics.

Ricardo Sánchez was a writer, poet, professor, and activist. Sometimes called the "Grandfather of Chicano poetry," Sánchez gained national acclaim for his 1971 poetry collection Canto y Grito Mi Liberacion. Incarcerated in his twenties for stealing money to feed his struggling family, Sánchez read extensively and even learned Hebrew while at Soledad Prison in California. Upon his release in 1969, his poems were included in a poetry anthology. In 1971, his first solo collection of poetry was published, establishing Sánchez as one of the nation's most important Chicano poets.