The Ngarinyin language, also known as Ungarinjin and Eastern Worrorran, is an endangered Australian Aboriginal language of the Kimberley region of Western Australia spoken by the Ngarinyin people.

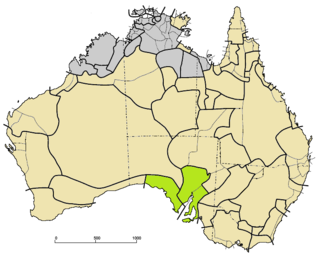

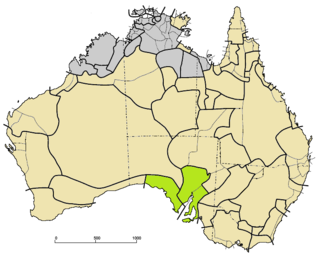

The Yura or Thura-Yura languages are a group of Australian Aboriginal languages surrounding Spencer Gulf and Gulf St Vincent in South Australia, that comprise a genetic language family of the Pama–Nyungan family.

The Barngarla, formerly known as Parnkalla and also known as Pangkala, are an Aboriginal people of the Port Lincoln, Whyalla and Port Augusta areas. The Barngarla are the traditional owners of much of Eyre Peninsula, South Australia.

The Wilyakali or Wiljaali are an Australian aboriginal tribal group of the Darling River basin in Far West New South Wales, Australia. Their traditional lands centred on the towns of Broken Hill and Silverton and surrounding country. Today the Wilyakali ancestors of Broken Hill are still living within Broken Hill and surrounding areas the lack of information on this tribe is far and few as they have been declared extinct or critically endangered.

The Maraura or Marrawarra people are an Aboriginal group whose traditional lands are located in Far West New South Wales and South Australia, Australia.

The Banbai are an Indigenous Australian people of New South Wales.

The Arnga are an indigenous Australian people of the northern Kimberley region of Western Australia.

The Ngarinman or Ngarinyman people are an Aboriginal Australian people of the Northern Territory who spoke the Ngarinyman language.

The Ngalia, or Ngalea, are an Aboriginal Australian people of the Western Desert cultural bloc resident in land extending from Western Australia to the west of South Australia. They are not to be confused with the Ngalia of the Northern Territory.

The Arabana, also known as the Ngarabana, are an Aboriginal Australian people of South Australia.

The Nyulnyul, also spelt Nyul Nyul, Njolnjol, Nyolnyol and other variants, are an Aboriginal Australian people of the Kimberley region of Western Australia.

The Yankuntjatjarra, otherwise written Jangkundjara, are an indigenous Australian people of the state of South Australia.

The Antakirinja, otherwise spelt Antakarinya, and alternatively spoken of as the Ngonde, are an indigenous Australian people of South Australia.

The Kuyani people, also written Guyani and other variants, and also known as the Nganitjidi, are an Aboriginal Australian people of the state of South Australia who speak the Kuyani language. Their traditional lands are to the west of the Flinders Ranges.

The Wangkangurru, also written Wongkanguru and Wangkanguru, are an Aboriginal Australian people of the Simpson Desert area in the state of South Australia. They also refer to themselves as Nharla.

The Wailpi are an indigenous people of South Australia They are also known as the Adnyamathanha, which also refers to a larger group, though they speak a dialect of the Adnyamathanha language.

The Wirangu are an Aboriginal Australian people of the Western coastal region of South Australia.

The Kunggara, also known as Kuritjara, are an indigenous Australian people of the southern Cape York Peninsula in Queensland.

The Yungkurara were an indigenous Australian people of the state of Queensland.

The Wagiman, also spelt Wagoman, Wagaman, Wogeman, and other variants, are an Aboriginal Australian people of the Northern Territory.