Baldr is a god in Germanic mythology. In Norse mythology, he is a son of the god Odin and the goddess Frigg, and has numerous brothers, such as Thor and Váli. In wider Germanic mythology, the god was known in Old English as Bældæġ, and in Old High German as Balder, all ultimately stemming from the Proto-Germanic theonym *Balðraz.

In Norse mythology, Heimdall is a god. He is the son of Odin and nine mothers. Heimdall keeps watch for invaders and the onset of Ragnarök from his dwelling Himinbjörg, where the burning rainbow bridge Bifröst meets the sky. He is attested as possessing foreknowledge and keen senses, particularly eyesight and hearing. The god and his possessions are described in enigmatic manners. For example, Heimdall is emerald-toothed, "the head is called his sword," and he is "the whitest of the gods."

In Norse mythology, Njörðr is a god among the Vanir. Njörðr, father of the deities Freyr and Freyja by his unnamed sister, was in an ill-fated marriage with the goddess Skaði, lives in Nóatún and is associated with the sea, seafaring, wind, fishing, wealth, and crop fertility.

Yggdrasil is an immense and central sacred tree in Norse cosmology. Around it exists all else, including the Nine Worlds.

Hávamál is presented as a single poem in the Codex Regius, a collection of Old Norse poems from the Viking age. The poem, itself a combination of numerous shorter poems, is largely gnomic, presenting advice for living, proper conduct and wisdom. It is considered an important source of Old Norse philosophy.

The Poetic Edda is the modern name for an untitled collection of Old Norse anonymous narrative poems. It is distinct from the Prose Edda written by Snorri Sturluson, although both works are seminal to the study of Old Norse poetry. Several versions of the Poetic Edda exist: especially notable is the medieval Icelandic manuscript Codex Regius, which contains 31 poems. The Codex Regius is arguably the most important extant source on Norse mythology and Germanic heroic legends. Since the early 19th century, it has had a powerful influence on Scandinavian literature, not only through its stories, but also through the visionary force and the dramatic quality of many of the poems. It has also been an inspiration for later innovations in poetic meter, particularly in Nordic languages, with its use of terse, stress-based metrical schemes that lack final rhymes, instead focusing on alliterative devices and strongly concentrated imagery. Poets who have acknowledged their debt to the Codex Regius include Vilhelm Ekelund, August Strindberg, J. R. R. Tolkien, Ezra Pound, Jorge Luis Borges, and Karin Boye.

Bestla is a jötunn in Norse mythology, and the mother of the gods Odin, Vili and Vé. She is also the sister of an unnamed man who assisted Odin, and the daughter of the jötunn Bölþorn. Odin is frequently called "Bestla's son" in both skaldic verses and the Poetic Edda.

Bölþorn is a jötunn in Norse mythology, and the father of Bestla, herself the mother of Odin, Vili and Vé.

In Norse mythology, Dellingr is a god. Dellingr is attested in the Poetic Edda, compiled in the 13th century from earlier traditional sources, and in the Prose Edda, written in the 13th century by Snorri Sturluson. In both sources, Dellingr is described as the father of Dagr, the personified day. The Prose Edda adds that, depending on manuscript variation, he is either the third husband of Nótt, the personified night, or the husband of Jörð, the personified earth. Dellingr is also attested in the legendary saga Hervarar saga ok Heiðreks. Scholars have proposed that Dellingr is the personified dawn and his name may appear both in an English surname and place name.

In Norse mythology, Dvalinn is a dwarf (Hjort) who appears in several Old Norse tales and kennings. The name translates as "the dormant one" or "the one slumbering". Dvalinn is listed as one of the four stags of Yggdrasill in both Grímnismál from the Poetic Edda and Gylfaginning from the Prose Edda.

In Norse mythology, Óðr or Óð, sometimes anglicized as Odr or Od, is a figure associated with the major goddess Freyja. The Prose Edda and Heimskringla, written in the 13th century by Snorri Sturluson, both describe Óðr as Freyja's husband and father of her daughter Hnoss. Heimskringla adds that the couple produced another daughter, Gersemi. A number of theories have been proposed about Óðr, generally that he is a hypostasis of the deity Odin due to their similarities.

A hörgr or hearg is a type of altar or cult site, possibly consisting of a heap of stones, used in Norse religion, as opposed to a roofed hall used as a hof (temple).

Máni is the Moon personified in Germanic mythology. Máni, personified, is attested in the Poetic Edda, compiled in the 13th century from earlier traditional sources, and the Prose Edda, written in the 13th century by Snorri Sturluson. Both sources state that he is the brother of the personified sun, Sól, and the son of Mundilfari, while the Prose Edda adds that he is followed by the children Hjúki and Bil through the heavens. As a proper noun, Máni appears throughout Old Norse literature. Scholars have proposed theories about Máni's potential connection to the Northern European notion of the Man in the Moon, and a potentially otherwise unattested story regarding Máni through skaldic kennings.

Sól or Sunna is the Sun personified in Germanic mythology. One of the two Old High German Merseburg Incantations, written in the 9th or 10th century CE, attests that Sunna is the sister of Sinthgunt. In Norse mythology, Sól is attested in the Poetic Edda, compiled in the 13th century from earlier traditional sources, and the Prose Edda, written in the 13th century by Snorri Sturluson.

In Norse mythology, Mímisbrunnr is a well associated with the being Mímir, located beneath the world tree Yggdrasil. Mímisbrunnr is attested in the Poetic Edda, compiled in the 13th century from earlier traditional sources, and the Prose Edda, written in the 13th century by Snorri Sturluson. The well is located beneath one of three roots of the world tree Yggdrasil, a root that passes into the Jötunheimr where the primordial plane of Ginnungagap once existed. In addition, the Prose Edda relates that the water of the well contains much wisdom, and that Odin sacrificed one of his eyes to the well in exchange for a drink. In the Prose Edda, Mímisbrunnr is mentioned as one of three wells existing beneath three roots of Yggdrasil, the other two being Hvergelmir, located beneath a root in Niflheim, and Urðarbrunnr.

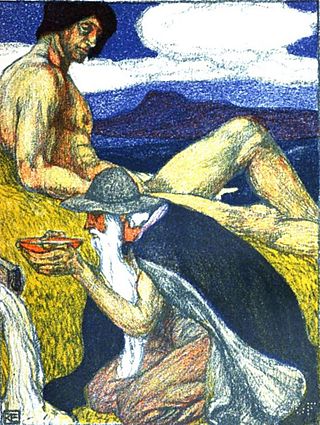

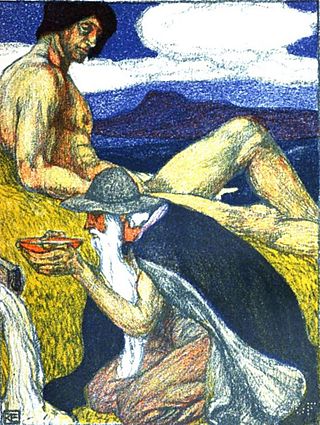

In Norse mythology, Sága is a goddess associated with the location Sökkvabekkr. At Sökkvabekkr, Sága and the god Odin merrily drink as cool waves flow. Both Sága and Sökkvabekkr are attested in the Poetic Edda, compiled in the 13th century from earlier traditional sources, and in the Prose Edda, written in the 13th century by Snorri Sturluson. Scholars have proposed theories about the implications of the goddess and her associated location, including that the location may be connected to the goddess Frigg's fen residence Fensalir and that Sága may be another name for Frigg.

Death in Norse paganism was associated with diverse customs and beliefs that varied with time, location and social group, and did not form a structured, uniform system. After the funeral, the individual could go to a range of afterlives including Valhalla, Hel and living on physically in the landscape. These afterlives show blurred boundaries and exist alongside a number of minor afterlives that may have been significant in Nordic paganism. The dead were also seen as being able to bestow land fertility, often in return for votive offerings, and knowledge, either willingly or after coercion. Many of these beliefs and practices continued in altered forms after the Christianisation of the Germanic peoples in folk belief.

Odin is a widely revered god in Germanic paganism. Norse mythology, the source of most surviving information about him, associates him with wisdom, healing, death, royalty, the gallows, knowledge, war, battle, victory, sorcery, poetry, frenzy, and the runic alphabet, and depicts him as the husband of the goddess Frigg. In wider Germanic mythology and paganism, the god was also known in Old English as Wōden, in Old Saxon as Uuôden, in Old Dutch as Wuodan, in Old Frisian as Wêda, and in Old High German as Wuotan, all ultimately stemming from the Proto-Germanic theonym *Wōðanaz, meaning 'lord of frenzy', or 'leader of the possessed'.

Germanic heroic legend is the heroic literary tradition of the Germanic-speaking peoples, most of which originates or is set in the Migration Period. Stories from this time period, to which others were added later, were transmitted orally, traveled widely among the Germanic speaking peoples, and were known in many variants. These legends typically reworked historical events or personages in the manner of oral poetry, forming a heroic age. Heroes in these legends often display a heroic ethos emphasizing honor, glory, and loyalty above other concerns. Like Germanic mythology, heroic legend is a genre of Germanic folklore.

Jackson W. Crawford is an American scholar, translator and poet who specializes in Old Norse. He previously taught at University of Colorado, Boulder (2017-2020), University of California, Berkeley (2014-17) and University of California, Los Angeles (2011–14). Crawford has a YouTube channel focused on Old Norse language, literature and mythology.