Ancient Egyptian religion was a complex system of polytheistic beliefs and rituals that formed an integral part of ancient Egyptian culture. It centered on the Egyptians' interactions with many deities believed to be present and in control of the world. About 1500 deities are known. Rituals such as prayer and offerings were provided to the gods to gain their favor. Formal religious practice centered on the pharaohs, the rulers of Egypt, believed to possess divine powers by virtue of their positions. They acted as intermediaries between their people and the gods, and were obligated to sustain the gods through rituals and offerings so that they could maintain Ma'at, the order of the cosmos, and repel Isfet, which was chaos. The state dedicated enormous resources to religious rituals and to the construction of temples.

Osiris is the god of fertility, agriculture, the afterlife, the dead, resurrection, life, and vegetation in ancient Egyptian religion. He was classically depicted as a green-skinned deity with a pharaoh's beard, partially mummy-wrapped at the legs, wearing a distinctive atef crown, and holding a symbolic crook and flail. He was one of the first to be associated with the mummy wrap. When his brother Set cut him up into pieces after killing him, Osiris' wife Isis found all the pieces and wrapped his body up, enabling him to return to life. Osiris was widely worshipped until the decline of ancient Egyptian religion during the rise of Christianity in the Roman Empire.

Isis was a major goddess in ancient Egyptian religion whose worship spread throughout the Greco-Roman world. Isis was first mentioned in the Old Kingdom as one of the main characters of the Osiris myth, in which she resurrects her slain brother and husband, the divine king Osiris, and produces and protects his heir, Horus. She was believed to help the dead enter the afterlife as she had helped Osiris, and she was considered the divine mother of the pharaoh, who was likened to Horus. Her maternal aid was invoked in healing spells to benefit ordinary people. Originally, she played a limited role in royal rituals and temple rites, although she was more prominent in funerary practices and magical texts. She was usually portrayed in art as a human woman wearing a throne-like hieroglyph on her head. During the New Kingdom, as she took on traits that originally belonged to Hathor, the preeminent goddess of earlier times, Isis was portrayed wearing Hathor's headdress: a sun disk between the horns of a cow.

The Osiris myth is the most elaborate and influential story in ancient Egyptian mythology. It concerns the murder of the god Osiris, a primeval king of Egypt, and its consequences. Osiris's murderer, his brother Set, usurps his throne. Meanwhile, Osiris's wife Isis restores her husband's body, allowing him to posthumously conceive their son, Horus. The remainder of the story focuses on Horus, the product of the union of Isis and Osiris, who is at first a vulnerable child protected by his mother and then becomes Set's rival for the throne. Their often violent conflict ends with Horus's triumph, which restores maat to Egypt after Set's unrighteous reign and completes the process of Osiris's resurrection.

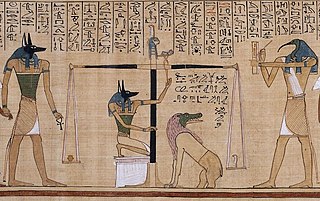

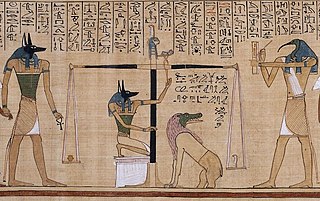

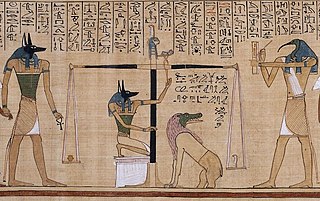

Ammit was an ancient Egyptian goddess with the forequarters of a lion, the hindquarters of a hippopotamus, and the head of a crocodile—the three largest "man-eating" animals known to ancient Egyptians. In ancient Egyptian religion, Ammit played an important role during the funerary ritual, the Judgment of the Dead.

In Egyptian mythology, Wepwawet was originally a deity of funerary rites, war, and royalty association, whose cult centre was Asyut in Upper Egypt. His name means opener of the ways and he is often depicted as a wolf standing at the prow of a solar-boat. Some interpret that Wepwawet was seen as a scout, going out to clear routes for the army to proceed forward. One inscription from the Sinai states that Wepwawet "opens the way" to king Sekhemkhet's victory.

The ancient Egyptians believed that a soul was made up of many parts. In addition to these components of the soul, there was the human body.

Natron is a naturally occurring mixture of sodium carbonate decahydrate (Na2CO3·10H2O, a kind of soda ash) and around 17% sodium bicarbonate (also called baking soda, NaHCO3) along with small quantities of sodium chloride and sodium sulfate. Natron is white to colourless when pure, varying to gray or yellow with impurities. Natron deposits are sometimes found in saline lake beds which arose in arid environments. Throughout history natron has had many practical applications that continue today in the wide range of modern uses of its constituent mineral components.

The Book of the Dead is an ancient Egyptian funerary text generally written on papyrus and used from the beginning of the New Kingdom to around 50 BC. The original Egyptian name for the text, transliterated r(ꜣ)w n(y)w prt m hrw(w), is translated as Book of Coming Forth by Day or Book of Emerging Forth into the Light. "Book" is the closest term to describe the loose collection of texts consisting of a number of magic spells intended to assist a dead person's journey through the Duat, or underworld, and into the afterlife and written by many priests over a period of about 1,000 years. In 1842, the Egyptologist Karl Richard Lepsius introduced for these texts the German name Todtenbuch, translated to English as 'Book of the Dead'.

In Ancient Egyptian religion, Taweret is the protective ancient Egyptian goddess of childbirth and fertility. The name "Taweret" means "she who is great" or simply "great one", a common pacificatory address to dangerous deities. The deity is typically depicted as a bipedal female hippopotamus with feline attributes, pendulous female human breasts, the limbs and paws of a lion, and the back and tail of a Nile crocodile. She commonly bears the epithets "Lady of Heaven", "Mistress of the Horizon", "She Who Removes Water", "Mistress of Pure Water", and "Lady of the Birth House".

The Eye of Horus, also known as left wedjat eye or udjat eye, specular to the Eye of Ra, is a concept and symbol in ancient Egyptian religion that represents well-being, healing, and protection. It derives from the mythical conflict between the god Horus with his rival Set, in which Set tore out or destroyed one or both of Horus's eyes and the eye was subsequently healed or returned to Horus with the assistance of another deity, such as Thoth. Horus subsequently offered the eye to his deceased father Osiris, and its revitalizing power sustained Osiris in the afterlife. The Eye of Horus was thus equated with funerary offerings, as well as with all the offerings given to deities in temple ritual. It could also represent other concepts, such as the moon, whose waxing and waning was likened to the injury and restoration of the eye.

The ancient Egyptians had an elaborate set of funerary practices that they believed were necessary to ensure their immortality after death. These rituals included mummifying the body, casting magic spells, and burials with specific grave goods thought to be needed in the afterlife.

The Coffin Texts are a collection of ancient Egyptian funerary spells written on coffins beginning in the First Intermediate Period. They are partially derived from the earlier Pyramid Texts, reserved for royal use only, but contain substantial new material related to everyday desires, indicating a new target audience of common people. Coffin texts are dated back to 2100 BCE. Ordinary Egyptians who could afford a coffin had access to these funerary spells and the pharaoh no longer had exclusive rights to an afterlife.

The Pyramid Texts are the oldest ancient Egyptian funerary texts, dating to the late Old Kingdom. They are the earliest known corpus of ancient Egyptian religious texts. Written in Old Egyptian, the pyramid texts were carved onto the subterranean walls and sarcophagi of pyramids at Saqqara from the end of the Fifth Dynasty, and throughout the Sixth Dynasty of the Old Kingdom, and into the Eighth Dynasty of the First Intermediate Period. The oldest of the texts have been dated to c. 2400–2300 BCE.

The four sons of Horus were a group of four deities in ancient Egyptian religion who were believed to protect deceased people in the afterlife. Beginning in the First Intermediate Period of Egyptian history, Imsety, Hapy, Duamutef, and Qebehsenuef were especially connected with the four canopic jars that housed the internal organs that were removed from the body of the deceased during the process of mummification. Most commonly, Imsety protected the liver, Hapy the lungs, Duamutef the stomach, and Qebehsenuef the intestines, but this pattern often varied. The canopic jars were given lids that represented the heads of the sons of Horus. Although they were originally portrayed as humans, in the latter part of the New Kingdom, they took on their most distinctive iconography, in which Imsety is portrayed as a human, Hapy as a baboon, Duamutef as a jackal, and Qebehsenuef as a falcon. The four sons were also linked with stars in the sky, with regions of Egypt, and with the cardinal directions.

The pyramid of Unas is a smooth-sided pyramid built in the 24th century BC for the Egyptian pharaoh Unas, the ninth and final king of the Fifth Dynasty. It is the smallest Old Kingdom pyramid, but significant due to the discovery of Pyramid Texts, spells for the king's afterlife incised into the walls of its subterranean chambers. Inscribed for the first time in Unas's pyramid, the tradition of funerary texts carried on in the pyramids of subsequent rulers, through to the end of the Old Kingdom, and into the Middle Kingdom through the Coffin Texts that form the basis of the Book of the Dead.

Egyptian mythology is the collection of myths from ancient Egypt, which describe the actions of the Egyptian gods as a means of understanding the world around them. The beliefs that these myths express are an important part of ancient Egyptian religion. Myths appear frequently in Egyptian writings and art, particularly in short stories and in religious material such as hymns, ritual texts, funerary texts, and temple decoration. These sources rarely contain a complete account of a myth and often describe only brief fragments.

Ancient Egyptian afterlife beliefs were centered around a variety of complex rituals that were influenced by many aspects of Egyptian culture. Religion was a major contributor, since it was an important social practice that bound all Egyptians together. For instance, many of the Egyptian gods played roles in guiding the souls of the dead through the afterlife. With the evolution of writing, religious ideals were recorded and quickly spread throughout the Egyptian community. The solidification and commencement of these doctrines were formed in the creation of afterlife texts which illustrated and explained what the dead would need to know in order to complete the journey safely.

The leopard skin was a ritual garment in Ancient Egypt. It has been documented with certainty since the Early Dynastic period. The mythological roots go back to the pre-dynastic period. In these times, the goddess Mafdet still served as the sky goddess, and her cosmic functions were taken over by the sky goddess Nut in the course of ancient Egyptian history. The Ancient Egyptians therefore used the term "leopard skin" in connection with the divine panther.