Climbing is the activity of using one's hands, feet, or other parts of the body to ascend a steep topographical object that can range from the world's tallest mountains to small boulders. Climbing is done for locomotion, sporting recreation, for competition, and is also done in trades that rely on ascension, such as construction and military operations. Climbing is done indoors and outdoors, on natural surfaces, and on artificial surfaces

Glossary of climbing terms relates to rock climbing, mountaineering, and to ice climbing.

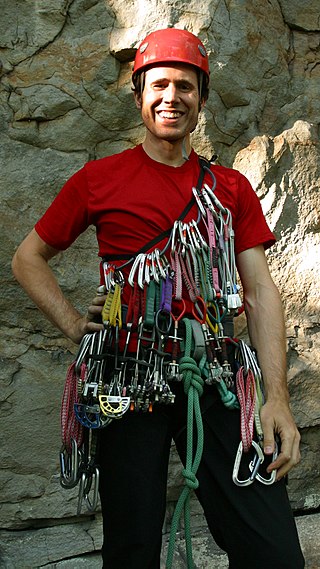

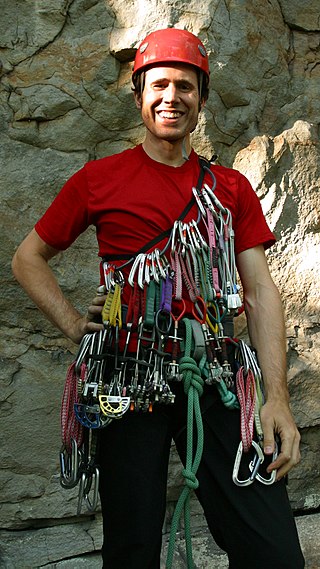

Rock-climbing equipment varies with the specific type of climbing that is undertaken. Bouldering needs the least equipment outside of climbing shoes, climbing chalk and optional crash pads. Sport climbing adds ropes, harnesses, belay devices, and quickdraws to clip into pre-drilled bolts. Traditional climbing adds the need to carry a "rack" of temporary passive and active protection devices. Multi-pitch climbing, and the related big wall climbing, adds devices to assist in ascending and descending fixed ropes. Finally, aid climbing uses unique equipment to give mechanical assistance to the climber in their upward movement.

Abseiling, also known as rappelling, is the controlled descent of a steep slope, such as a rock face, by moving down a rope. When abseiling, the person descending controls their own movement down a static or fixed rope, in contrast to lowering off, in which the rope attached to the person descending is paid out by their belayer.

Solo climbing, or soloing, is a style of climbing in which the climber climbs a route alone, without the assistance of a belayer. By its very nature, it presents a higher degree of risk to the climber, and in some cases, is considered extremely high risk.

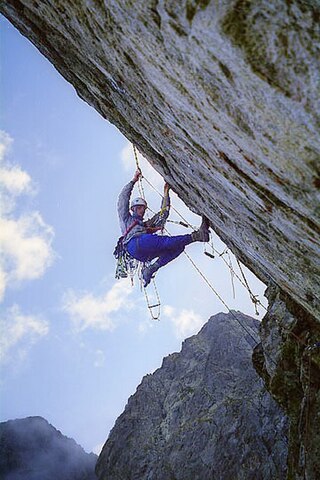

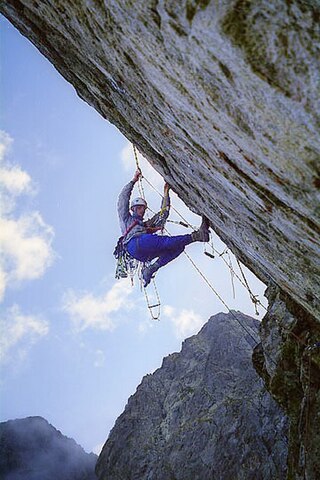

Aid climbing is a form of rock climbing that uses mechanical devices and equipment, such as aiders, for upward momentum. Aid climbing is different than free climbing, which only uses mechanical equipment for protection, but not to assist in upward momentum. Aid climbing sometimes involves hammering in permanent pitons and bolts, into which the aiders are clipped, but there is also 'clean aid climbing' which avoids any hammering, and only uses removable placements.

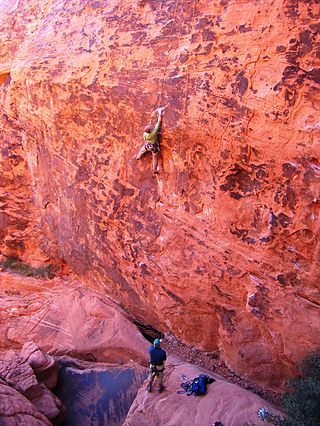

In climbing and mountaineering, belaying comprises techniques used to create friction within a climbing protection system, particularly on a climbing rope, so that a falling climber does not fall very far. A climbing partner typically applies tension at the other end of the rope whenever the climber is not moving, and removes the tension from the rope whenever the climber needs more rope to continue climbing. The belay is the place where the belayer is anchored, which is typically on the ground, or on ledge but may also be a hanging belay where the belayer themself is suspended from an anchor in the rock on a multi-pitch climb.

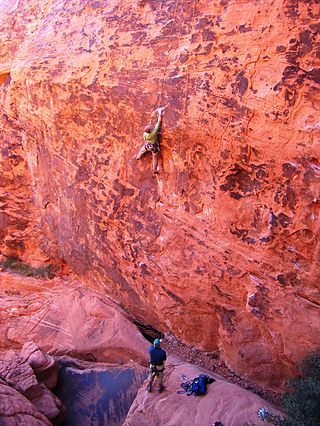

Lead climbing is a technique in rock climbing where the lead climber clips their rope to the climbing protection as they ascend a pitch of the climbing route, while their second remains at the base of the route belaying the rope to protect the lead climber in the event that they fall. The term is used to distinguish between the two roles, and the greater effort and increased risk, of the role of the lead climber.

Top rope climbing is a form of rock climbing where the climber is securely attached to a climbing rope that runs through a fixed anchor at the top of the climbing route, and back down to the belayer at the base of the climb. A climber who falls will just hang from the rope at the point of the fall, and can then either resume their climb or have the belayer lower them down in a controlled manner to the base of the climb. Climbers on indoor climbing walls can use mechanical auto belay devices to top rope alone.

Rock climbing is a sport in which participants climb up, across, or down natural rock formations or indoor climbing walls. The goal is to reach the summit of a formation or the endpoint of a usually pre-defined route without falling. Rock climbing is a physically and mentally demanding sport, one that often tests a climber's strength, endurance, agility and balance along with mental control. Knowledge of proper climbing techniques and the use of specialized climbing equipment is crucial for the safe completion of routes.

Multi-pitch climbing is a type of climbing that typically takes place on routes that are more than a single rope length in height, and thus where the lead climber cannot complete the climb as a single pitch. Where the number of pitches exceeds 6–10, it can become big wall climbing, or where the pitches are in a mixed rock and ice mountain environment, it can become alpine climbing. Multi-pitch rock climbs can come in traditional, sport, and aid formats. Some have free soloed multi-pitch routes.

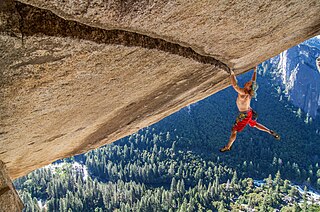

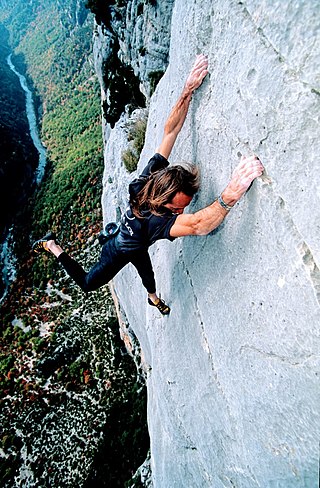

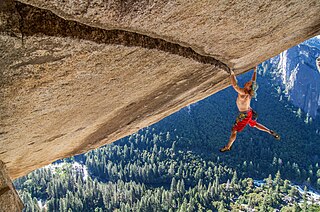

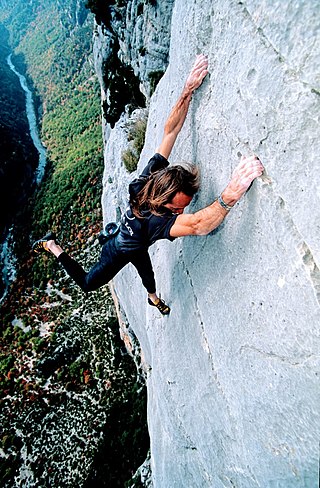

Free solo climbing, or free soloing, is a form of rock climbing where the climbers climb solo without ropes or other protective equipment, using only their climbing shoes and their climbing chalk. Free soloing is the most dangerous form of climbing, and, unlike bouldering, free soloists climb above safe heights, where a fall can be fatal. Though many climbers have free soloed climbing grades they are very comfortable on, only a tiny group free solo regularly, and at grades closer to the limit of their abilities.

In climbing and mountaineering, a fixed-rope is the practice of installing networks of in-situ anchored static climbing ropes on climbing routes to assist any following climbers to ascend more rapidly—and with less effort—by using mechanical aid devices called ascenders. Fixed ropes also allow climbers to descend rapidly using mechanical devices called descenders. Fixed ropes also help to identify the line of the climbing route in periods of low visibility. The act of ascending a fixed rope is also called jumaring, which is the name of a type of ascender device, or also called jugging in the US.

Rope-solo climbing or rope-soloing is a form of solo climbing, but unlike with free solo climbing, which is also performed alone and with no climbing protection whatsoever, the rope-solo climber uses a mechanical self-belay device and rope system, which enables them to use the standard climbing protection to protect themselves in the event of a fall.

A dynamic rope is a specially constructed, somewhat elastic rope used primarily in rock climbing, ice climbing, and mountaineering. This elasticity, or stretch, is the property that makes the rope dynamic—in contrast to a static rope that has only slight elongation under load. Greater elasticity allows a dynamic rope to more slowly absorb the energy of a sudden load, such from arresting a climber's fall, by reducing the peak force on the rope and thus the probability of the rope's catastrophic failure. A kernmantle rope is the most common type of dynamic rope now used. Since 1945, nylon has, because of its superior durability and strength, replaced all natural materials in climbing rope.

Big wall climbing is a form of rock climbing that takes place on long multi-pitch routes that normally require a full day, if not several days, to ascend. In addition, big wall routes are typically sustained and exposed, where the climbers remain suspended from the rock face, even sleeping hanging from the face, with limited options to sit down or escape unless they abseil back down the whole route, which is a complex and risky action. It is therefore a physically and mentally demanding form of climbing.

Self-rescue is a group of techniques in climbing and mountaineering where the climber(s) – sometimes having just been severely injured – use their equipment to retreat from dangerous or difficult situations on a given climbing route without calling on third party search and rescue (SAR) or mountain rescue services for help.

Simul-climbing is a climbing technique where a pair of climbers who are attached by a rope simultaneously ascend a multi-pitch climbing route. It contrasts with lead climbing where the leader ascends a given pitch on the route while the second climber remains in a fixed position to belay the leader in case they fall. Simul-climbing is not free solo climbing, as the lead simul-climber will clip the rope into points of climbing protection as they ascend. Simul-climbing is different from a rope team and short-roping, which are used for flatter terrain that doesn't typically need protection points.

In climbing and mountaineering, a traverse is a section of a climbing route where the climber moves laterally, as opposed to in an upward direction. The term has broad application, and its use can range from describing a brief section of lateral movement on a pitch of a climbing route, to large multi-pitch climbing routes that almost entirely consist of lateral movement such as girdle traverses that span the entire rock face of a crag, to mountain traverses that span entire ridges connecting chains of mountain peaks.

A rope team is a climbing technique where two or more climbers who are attached to a single climbing rope move simultaneously together along easy-angled terrain that does not require points of fixed climbing protection to be inserted along the route. Rope teams contrast with simul-climbing, which involves only two climbers and where they are ascending steep terrain that will require many points of protection to be inserted along the route. A specific variant of a rope team is the technique of short-roping, which is used by mountain guides to help weaker clients, and which also does not employ fixed climbing protection points.