The Levant is an approximate historical geographical term referring to a large area in the Eastern Mediterranean region of West Asia and core territory of the political term Middle East. In its narrowest sense, which is in use today in archaeology and other cultural contexts, it is equivalent to Cyprus and a stretch of land bordering the Mediterranean Sea in western Asia: i.e. the historical region of Syria, which includes present-day Israel, Jordan, Lebanon, Syria, the Palestinian territories and most of Turkey southwest of the middle Euphrates. Its overwhelming characteristic is that it represents the land bridge between Africa and Eurasia. In its widest historical sense, the Levant included all of the Eastern Mediterranean with its islands; that is, it included all of the countries along the Eastern Mediterranean shores, extending from Greece in Southern Europe to Cyrenaica, Eastern Libya in Northern Africa.

The Semitic languages are a branch of the Afroasiatic language family. They include Arabic, Amharic, Aramaic, Hebrew, and numerous other ancient and modern languages. They are spoken by more than 330 million people across much of West Asia, North Africa, the Horn of Africa, Malta, and in large immigrant and expatriate communities in North America, Europe, and Australasia. The terminology was first used in the 1780s by members of the Göttingen school of history, who derived the name from Shem, one of the three sons of Noah in the Book of Genesis.

Samaria is the Hellenized form of the Hebrew name Shomron, used as a historical and biblical name for the central region of Israel, bordered by Judea to the south and Galilee to the north. The region is known to the Palestinians in Arabic under two names, Samirah, and Mount Nablus.

The Jezreel Valley, or Marj Ibn Amir, also known as the Valley of Megiddo, is a large fertile plain and inland valley in the Northern District of Israel. It is bordered to the north by the highlands of the Lower Galilee region, to the south by the Samarian highlands, to the west and northwest by the Mount Carmel range, and to the east by the Jordan Valley, with Mount Gilboa marking its southern extent. The largest settlement in the valley is the city of Afula, which lies near its center.

The Canaanite languages, sometimes referred to as Canaanite dialects, are one of three subgroups of the Northwest Semitic languages, the others being Aramaic and Amorite. These closely related languages originate in the Levant and Mesopotamia, and were spoken by the ancient Semitic-speaking peoples of an area encompassing what is today Israel, Jordan, the Sinai Peninsula, Lebanon, Syria, Palestine, as well as some areas of southwestern Turkey (Anatolia), western and southern Iraq (Mesopotamia) and the northwestern corner of Saudi Arabia.

Biblical Hebrew, also called Classical Hebrew, is an archaic form of the Hebrew language, a language in the Canaanite branch of Semitic languages spoken by the Israelites in the area known as the Land of Israel, roughly west of the Jordan River and east of the Mediterranean Sea. The term "Hebrew" (ivrit) was not used for the language in the Hebrew Bible, which was referred to as שְֹפַת כְּנַעַן or יְהוּדִית, but the name was used in Ancient Greek and Mishnaic Hebrew texts.

Gezer, or Tel Gezer, in Arabic: تل الجزر – Tell Jezar or Tell el-Jezari is an archaeological site in the foothills of the Judaean Mountains at the border of the Shfela region roughly midway between Jerusalem and Tel Aviv. It is now an Israeli national park. In the Hebrew Bible, Gezer is associated with Joshua and Solomon.

Over recorded history, there have been many names of the Levant, a large area in the Near East, or its constituent parts. These names have applied to a part or the whole of the Levant. On occasion, two or more of these names have been used at the same time by different cultures or sects. As a natural result, some of the names of the Levant are highly politically charged. Perhaps the least politicized name is Levant itself, which simply means "where the sun rises" or "where the land rises out of the sea", a meaning attributed to the region's easterly location on the shore of the Mediterranean Sea.

Proto-Canaanite is the name given to

The Paleo-Hebrew script, also Palaeo-Hebrew, Proto-Hebrew or Old Hebrew, is the writing system found in inscriptions of Canaanite languages from the region of Southern Canaan, also known as biblical Israel and Judah. It is considered to be the script used to record the original texts of the Hebrew Bible due to its similarity to the Samaritan script, as the Talmud stated that the Hebrew ancient script was still used by the Samaritans. The Talmud described it as the "Libona'a script", translated by some as "Lebanon script". Use of the term "Paleo-Hebrew alphabet" is due to a 1954 suggestion by Solomon Birnbaum, who argued that "[t]o apply the term Phoenician [from Northern Canaan, today's Lebanon] to the script of the Hebrews [from Southern Canaan, today's Israel-Palestine] is hardly suitable". The Paleo-Hebrew and Phoenician alphabets are two slight regional variants of the same script.

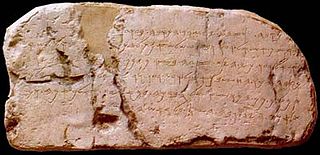

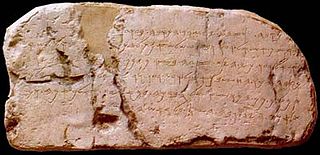

The Gezer calendar is a small limestone tablet with an early Canaanite inscription discovered in 1908 by Irish archaeologist R. A. Stewart Macalister in the ancient city of Gezer, 20 miles west of Jerusalem. It is commonly dated to the 10th century BCE, although the excavation was unstratified and its identification during the excavations was not in a "secure archaeological context", presenting uncertainty around the dating.

Bethoron, also Beth-Horon, was the name of two adjacent ancient towns strategically located on the Gibeon–Aijalon road, guarding the "ascent of Beth-Horon". The towns are mentioned in the Hebrew Bible and in other ancient sources: Upper Bethoron appears in Joshua 16:5, Lower Bethoron in Joshua 16:3, both in 1 Chronicles 7:24, and the ascent in I Maccabees 3:16.

Beit Ur al-Tahta is a Palestinian village located in the central West Bank, in the Ramallah and Al-Bireh Governorate of the State of Palestine. According to the Palestinian Central Bureau of Statistics, Beit Ur at-Tahta had a population of 5,040 inhabitants in 2017.

Levantine archaeology is the archaeological study of the Levant. It is also known as Syro-Palestinian archaeology or Palestinian archaeology. Besides its importance to the discipline of Biblical archaeology, the Levant is highly important when forming an understanding of the history of the earliest peoples of the Stone Age.

Beit Ur al-Fauqa is a Palestinian village located in the Ramallah and al-Bireh Governorate of the State of Palestine, in the northern West Bank, 14 kilometers (8.7 mi) west of Ramallah and 3 kilometers (1.9 mi) southeast of Beit Ur al-Tahta.

Tell ej-Judeideh is a tell in modern Israel, lying at an elevation of 398 metres (1,306 ft) above sea-level. The Arabic name is thought to mean, "Mound of the dykes." In Modern Hebrew, the ruin is known by the name Tell Goded.

Ancient Semitic-speaking peoples or Proto-Semitic people were speakers of Semitic languages who lived throughout the ancient Near East and North Africa, including the Levant, Mesopotamia, the Arabian Peninsula and Carthage from the 3rd millennium BC until the end of antiquity, with some, such as Arabs, Arameans, Assyrians, Jews, Mandaeans, and Samaritans having a continuum into the present day.

Hebrew-language names were coined for the place-names of Palestine throughout different periods under the British Mandate; after the establishment of Israel following the 1948 Palestinian expulsion and flight and 1948 Arab–Israeli War; and subsequently in the Palestinian territories occupied by Israel in 1967. A 1992 study counted c. 2,780 historical locations whose names were Hebraized, including 340 villages and towns, 1,000 Khirbat (ruins), 560 wadis and rivers, 380 springs, 198 mountains and hills, 50 caves, 28 castles and palaces, and 14 pools and lakes. Palestinians consider the Hebraization of place-names in Palestine part of the Palestinian Nakba.

The study of the origins of the Palestinians, a population encompassing the Arab inhabitants of the former Mandatory Palestine and their descendants, is a subject approached through an interdisciplinary lens, drawing from fields such as population genetics, demographic history, folklore, including oral traditions, linguistics, and other disciplines.