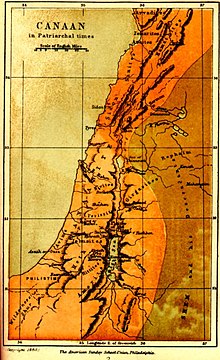

Yahweh was an ancient Levantine deity, and national god of the Israelite kingdoms of Israel and Judah. Though no consensus exists regarding the deity's origins, scholars generally contend that Yahweh is associated with Seir, Edom, Paran and Teman, and later with Canaan. The origins of his worship reach at least to the early Iron Age, and likely to the Late Bronze Age, if not somewhat earlier.

Baal, or Baʻal, was a title and honorific meaning 'owner' or 'lord' in the Northwest Semitic languages spoken in the Levant during antiquity. From its use among people, it came to be applied to gods. Scholars previously associated the theonym with solar cults and with a variety of unrelated patron deities, but inscriptions have shown that the name Ba'al was particularly associated with the storm and fertility god Hadad and his local manifestations.

ʼĒl is a Northwest Semitic word meaning 'god' or 'deity', or referring to any one of multiple major ancient Near Eastern deities. A rarer form, 'ila, represents the predicate form in the Old Akkadian and Amorite languages. The word is derived from the Proto-Semitic *ʔil-, meaning "god".

Qetesh was a goddess who was incorporated into the ancient Egyptian religion in the late Bronze Age. Her name was likely developed by the Egyptians based on the Semitic root Q-D-Š meaning 'holy' or 'blessed,' attested as a title of El and possibly Athirat and a further independent deity in texts from Ugarit.

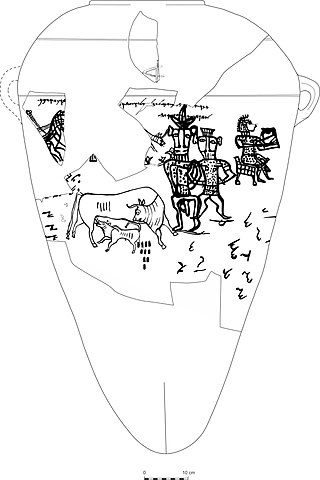

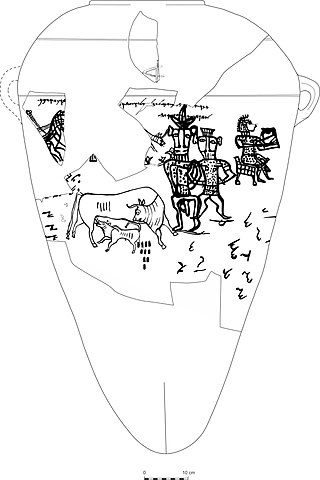

Hadad, Haddad, Adad, or Iškur (Sumerian) was the storm and rain god in the Canaanite and ancient Mesopotamian religions. He was attested in Ebla as "Hadda" in c. 2500 BCE. From the Levant, Hadad was introduced to Mesopotamia by the Amorites, where he became known as the Akkadian (Assyrian-Babylonian) god Adad. Adad and Iškur are usually written with the logogram 𒀭𒅎dIM—the same symbol used for the Hurrian god Teshub. Hadad was also called Pidar, Rapiu, Baal-Zephon, or often simply Baʿal (Lord), but this title was also used for other gods. The bull was the symbolic animal of Hadad. He appeared bearded, often holding a club and thunderbolt while wearing a bull-horned headdress. Hadad was equated with the Greek god Zeus, the Roman god Jupiter, as well as the Babylonian mythology Bel.

Dagon or Dagan was a god worshipped in ancient Syria across the middle of the Euphrates, with primary temples located in Tuttul and Terqa, though many attestations of his cult come from cities such as Mari and Emar as well. In settlements situated in the upper Euphrates area he was regarded as the "father of gods" similar to Mesopotamian Enlil or Hurrian Kumarbi, as well as a lord of the land, a god of prosperity, and a source of royal legitimacy. A large number of theophoric names, both masculine and feminine, attests that he was a popular deity. He was also worshiped further east, in Mesopotamia, where many rulers regarded him as the god capable of granting them kingship over the western areas.

Asherah is the great goddess in ancient Semitic religion. She also appears in Hittite writings as Ašerdu(s) or Ašertu(s). Her name was Aṯeratum to the Amorites, and Athiratu in Ugarit. Many scholars hold that Yahweh and Asherah were a consort pair in ancient Israel and Judah, although others disagree.

Mot was the Canaanite god of death and the Underworld. He was also known to the people of Ugarit and in Phoenicia, where Canaanite religion was widespread. The main source of information about Mot in Canaanite mythology comes from the texts discovered at Ugarit, but he is also mentioned in the surviving fragments of Philo of Byblos's Greek translation of the writings of the Phoenician Sanchuniathon.

Idolatry in Judaism is prohibited. Judaism holds that idolatry is not limited to the worship of an idol itself, but also worship involving any artistic representations of God. The prohibition is epitomized by the first two "words" of the decalogue: I am the Lord thy God, Thou shalt have no other gods before me, and Thou shalt not make unto thee any graven image or any image in the sky, on earth or in the sea. These prohibitions are re-emphasized repeatedly by the later prophets, suggesting the ongoing appeal of Canaanite religion and syncretic assimilation to the ancient Israelites.

Ancient Semitic religion encompasses the polytheistic religions of the Semitic peoples from the ancient Near East and Northeast Africa. Since the term Semitic itself represents a rough category when referring to cultures, as opposed to languages, the definitive bounds of the term "ancient Semitic religion" are only approximate, but exclude the religions of "non-Semitic" speakers of the region such as Egyptians, Elamites, Hittites, Hurrians, Mitanni, Urartians, Luwians, Minoans, Greeks, Phrygians, Lydians, Persians, Medes, Philistines and Parthians.

Baʽal Zephon, also transliterated as Baal-zephon, was an epithet of the Canaanite storm god Baʿal in his role as lord of Mount Zaphon; he is identified in the Ugaritic texts as Hadad. Because of the mountain's importance and location, it came to metonymously signify "north" in Hebrew; the name is therefore sometimes given in translation as Lord of the North. He was equated with the Greek god Zeus in his epithet Zeus Kasios and later with the Roman Jupiter Casius.

The religions of the ancient Near East were mostly polytheistic, with some examples of monolatry. Some scholars believe that the similarities between these religions indicate that the religions are related, a belief known as patternism.

Shalim is a pagan god in Canaanite religion, mentioned in inscriptions found in Ugarit. William F. Albright identified Shalim as the god of the dusk and Shahar as the god of the dawn. In the Dictionary of Deities and Demons in the Bible, Venus is represented by Shalim as the Evening Star and Shahar as the Morning Star. His name derives from the triconsonantal Semitic root Š-L-M.

Kothar-wa-Khasis, also known as Kothar or Hayyānu, was an Ugaritic god regarded as a divine artisan. He could variously play the roles of an architect, smith, musician or magician. Some scholars believe that this name represents two gods, Kothar and Khasis, combined into one.

The Baal Cycle is an Ugaritic cycle of stories about the Canaanite god Baʿal, a storm god associated with fertility. It is one of the Ugarit texts, dated to c. 1500–1300 BCE.

Baalshamin, also called Baal Shamem and Baal Shamaim, was a Northwest Semitic god and a title applied to different gods at different places or times in ancient Middle Eastern inscriptions, especially in Canaan/Phoenicia and Syria. The title was most often applied to Hadad, who is also often titled just Ba‘al. Baalshamin was one of the two supreme gods and the sky god of pre-Islamic Palmyra in ancient Syria. There his attributes were the eagle and the lightning bolt, and he perhaps formed a triad with the lunar god Aglibol and the sun god Malakbel. The title was also applied to Zeus.

The Early History of God: Yahweh and Other Deities in Ancient Israel is a book on the history of ancient Israelite religion by Mark S. Smith, Skirball Professor of Bible and Ancient Near Eastern Studies at New York University. The revised 2002 edition contains revisions to the original 1990 edition in light of intervening archaeological finds and studies.

Shapshu or Shapsh, and also Shamshu, was a Canaanite sun goddess. She also served as the royal messenger of the high god El, her probable father. Her most common epithets in the Ugaritic corpus are nrt ỉlm špš, rbt špš, and špš ʿlm. In the pantheon lists KTU 1.118 and 1.148, Shapshu is equated with the Akkadian dšamaš.

Yahwism, as it is called by modern scholars, was the religion of ancient Israel and Judah. An ancient Semitic religion of the Iron Age, Yahwism was essentially polytheistic and had a pantheon, with various gods and goddesses being worshipped by the Israelites. At the head of this pantheon was Yahweh—held in an especially high regard as the two Israelite kingdoms' national god—and his consort Asherah. Following this duo were second-tier gods and goddesses, such as Baal, Shamash, Yarikh, Mot, and Astarte, each of whom had their own priests and prophets and numbered royalty among their devotees.

Hauron, Haurun or Hawran was an ancient Egyptian god worshiped in Giza. He was closely associated with Harmachis, with the names in some cases used interchangeably, and his name as a result could be used as a designation of the Great Sphinx of Giza. While Egyptologists were familiar with Hauron since the nineteenth century, his origin was initially unknown, and only in the 1930s it was established that he originated outside Egypt. Today it is agreed that he was the Egyptian form of a god worshiped in Canaan and further north in the city of Ugarit, conventionally referred to as Horon in scholarship.