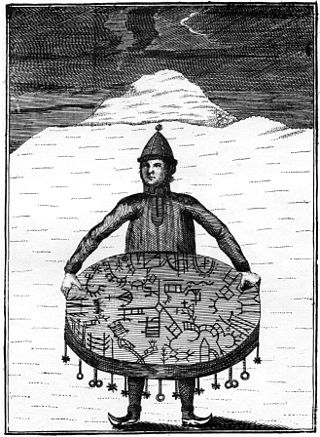

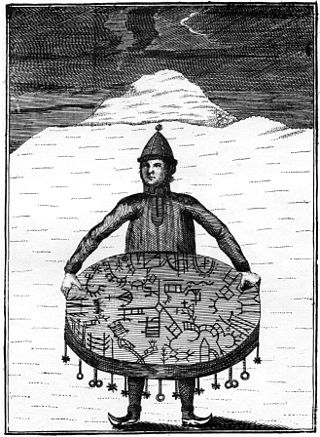

Shamanism or samanism is a religious practice that involves a practitioner interacting with the spirit world through altered states of consciousness, such as trance. The goal of this is usually to direct spirits or spiritual energies into the physical world for the purpose of healing, divination, or to aid human beings in some other way.

The Uralic languages form a language family of 42 languages spoken predominantly in Europe and North Asia. The Uralic languages with the most native speakers are Hungarian, Finnish, and Estonian. Other languages with speakers above 100,000 are Erzya, Moksha, Mari, Udmurt and Komi spoken in the European parts of the Russian Federation. Still smaller minority languages are Sámi languages of the northern Fennoscandia; other members of the Finnic languages, ranging from Livonian in northern Latvia to Karelian in northwesternmost Russia; and the Samoyedic languages, Mansi and Khanty spoken in Western Siberia.

The Samoyedic or Samoyed languages are spoken around the Ural Mountains, in northernmost Eurasia, by approximately 25,000 people altogether. They derive from a common ancestral language called Proto-Samoyedic, and form a branch of the Uralic languages. Having separated perhaps in the last centuries BC, they are not a diverse group of languages, and are traditionally considered to be an outgroup, branching off first from the other Uralic languages.

The Taymyr Peninsula is a peninsula in the Far North of Russia, in the Siberian Federal District, that forms the northernmost part of the mainland of Eurasia. Administratively it is part of the Krasnoyarsk Krai Federal subject of Russia.

Kets are a Yeniseian-speaking people in Siberia. During the Russian Empire, they were known as Ostyaks, without differentiating them from several other Siberian people. Later, they became known as Yenisei Ostyaks because they lived in the middle and lower basin of the Yenisei River in the Krasnoyarsk Krai district of Russia. The modern Kets lived along the eastern middle stretch of the river before being assimilated politically into Russia between the 17th and 19th centuries. According to the 2010 census, there were 1,220 Kets in Russia. According to the 2021 census, this number had declined to 1,088.

The Nganasans are a Uralic people of the Samoyedic branch native to the Taymyr Peninsula in north Siberia. In the Russian Federation, they are recognized as one of the Indigenous peoples of the Russian North. They reside primarily in the settlements of Ust-Avam, Volochanka, and Novaya in the Taymyrsky Dolgano-Nenetsky District of Krasnoyarsk Krai, with smaller populations residing in the towns of Dudinka and Norilsk as well.

A noaidi is a shaman of the Sami people in the Nordic countries, playing a role in Sámi religious practices. Most noaidi practices died out during the 17th century, most likely because they resisted Christianization of the Sámi people and the king's authority. Their actions were referred to in courts as "magic" or "sorcery". Several Sámi shamanistic beliefs and practices are similar to those of some Siberian cultures.

Natural sounds are any sounds produced by non-human organisms as well as those generated by natural, non-biological sources within their normal soundscapes. It is a category whose definition is open for discussion. Natural sounds create an acoustic space.

The Soyot are an ethnic group of Turkic origin who live mainly in the Oka region in the Okinsky District in Buryatia, Russia. They share much of their history with the Tofalar, Tozhu Tuvans, Dukha, and Buryat; the Soyot have taken on a great deal of Buryat cultural influence and were grouped together with them under Soviet policy. Due to intermarriage between Soyots and Buryats, the Soyot population is heavily mixed with the Buryat. In 2000, they were reinstated as a distinct ethnic group.

Hungarian mythology includes the myths, legends, folk tales, fairy tales and gods of the Hungarians, also known as the Magyarok.

Soul dualism, also called dualistic pluralism or multiple souls, is a range of beliefs that a person has two or more kinds of souls. In many cases, one of the souls is associated with body functions and the other one can leave the body. Sometimes the plethora of soul types can be even more complex. Sometimes, a shaman's "free soul" may be held to be able to undertake a spirit journey.

Traditional Alaskan Native religion involves mediation between people and spirits, souls, and other immortal beings. Such beliefs and practices were once widespread among Inuit, Yupik, Aleut, and Northwest Coastal Indian cultures, but today are less common. They were already in decline among many groups when the first major ethnological research was done. For example, at the end of the 19th century, Sagdloq, the last medicine man among what were then called in English, "Polar Eskimos", died; he was believed to be able to travel to the sky and under the sea, and was also known for using ventriloquism and sleight-of-hand.

Hungarian shamanism is discovered through comparative methods in ethnology, designed to analyse and search ethnographic data of Hungarian folktales, songs, language, comparative cultures, and historical sources.

The imitation of natural sounds in various cultures is a diverse phenomenon and can fill in various functions. In several instances, it is related to the belief system. It may serve also such practical goals as luring in the hunt; or entertainment.

Shamanism in various cultures shows great diversity. In some cultures, shamanic music may intentionally mimic natural sounds, sometimes with onomatopoeia. Imitation of natural sounds may also serve other functions not necessarily related to shamanism, such as luring in the hunt; and entertainment.

Elements of a Proto-Uralic religion can be recovered from reconstructions of the Proto-Uralic language.

Shamanic Music is ritualistic music used in religious and spiritual ceremonies associated with the practice of shamanism. Shamanic music makes use of various means of producing music, with an emphasis on voice and rhythm. It can vary based on cultural, geographic, and religious influences.

Eugene Arnoľdovič Helimski was a Soviet and Russian linguist. He was a Doctor of Philosophy (1988) and Professor.

The Proto-Uralic homeland is the hypothetical place where speakers of the Proto-Uralic language lived in a single linguistic community, or complex of communities, before this original language dispersed geographically and divided into separate distinct languages. Various locations have been proposed to be the Proto-Uralic homeland.

Shamanism is a religious practice present in various cultures and religions around the world. Shamanism takes on many different forms, which vary greatly by region and culture and are shaped by the distinct histories of its practitioners.