The Bengal cat is a breed of hybrid cat created from crossing of an Asian leopard cat, with domestic cats, especially the spotted Egyptian Mau. It is then usually bred with a breed that demonstrates a friendlier personality, because after breeding a domesticated cat with a wildcat, its friendly personality may not manifest in the kitten. The breed's name derives from the leopard cat's taxonomic name.

A domestic long-haired cat is a cat of mixed ancestry – thus not belonging to any particular recognized cat breed – possessing a coat of semi-long to long fur. Domestic long-haired cats should not be confused with the British Longhair, American Longhair, or other breeds with "Longhair" names, which are standardized breeds defined by various registries. Other generic terms are in British English, moggie and in American English alley cat. Domestic long-haired cats are the third most common type of cat in the United States.

The Munchkin is a breed of cat characterized by its very short legs, which are caused by genetic mutation. Compared to many other cat breeds, it is a relatively new breed, documented since 1940s and officially recognized in 1991. The Munchkin is considered to be the original breed of dwarf cat.

The serval is a wild cat native to Africa. It is widespread in sub-Saharan countries, except rainforest regions. Across its range, it occurs in protected areas, and hunting it is either prohibited or regulated in range countries.

The Saarlooswolfdog is a wolfdog breed originating from the Netherlands by the crossing of a German Shepherd with a Siberian grey wolf in 1935. The offspring were then further crossed with German Shepherds.

Purebreds are "cultivated varieties" of an animal species achieved through the process of selective breeding. When the lineage of a purebred animal is recorded, that animal is said to be "pedigreed". Purebreds breed true-to-type which means the progeny of like-to-like purebred parents will carry the same phenotype, or observable characteristics of the parents. A group of purebreds is called a pure-breeding line or strain.

A crossbreed is an organism with purebred parents of two different breeds, varieties, or populations. Crossbreeding, sometimes called "designer crossbreeding", is the process of breeding such an organism. While crossbreeding is used to maintain health and viability of organisms, irresponsible crossbreeding can also produce organisms of inferior quality or dilute a purebred gene pool to the point of extinction of a given breed of organism.

The Pixie-bob is a breed of domestic cat claimed to be the progeny of naturally occurring bobcat hybrids. However, DNA testing has failed to detect bobcat marker genes, and Pixie-bobs are considered wholly domestic for the purposes of ownership, cat fancy registration, and import and export. They were, however, selected and bred to look like American bobcats.

The Chausie is a domestic breed of cat that was developed by breeding a few individuals from the non-domestic species jungle cat to a far greater number of domestic cats. The Chausie was first recognized as a domestic breed by The International Cat Association (TICA) in 1995. Within the domestic breeds, the Chausie is categorized as a non-domestic hybrid source breed. Because Chausies are mostly descended from domestic cats, by about the fourth generation they are fully fertile and completely domestic in temperament.

The Sokoke is natural breed of domestic cat, developed and standardised, beginning in the late 1970s, from the feral khadzonzo landrace of eastern, coastal Kenya. The Sokoke is recognized by four major cat pedigree registry organizations as a standardised cat breed. It is named after the Arabuko Sokoke National Forest, the environment from which the foundation stock was obtained, for breed development primarily in Denmark and the United States. The cat is long-legged, with short, coarse hair, and typically a tabby coat, though specific lineages have produced different appearances. Although once rumored to be a domestic × wildcat hybrid, genetic study has not borne out this belief. Another idea, that the variety is unusually ancient, remains unproven either way. The native population is closely related to an island-dwelling group, the Lamu cat, further north.

An F1 hybrid (also known as filial 1 hybrid) is the first filial generation of offspring of distinctly different parental types. F1 hybrids are used in genetics, and in selective breeding, where the term F1 crossbreed may be used. The term is sometimes written with a subscript, as F1 hybrid. Subsequent generations are called F2, F3, etc.

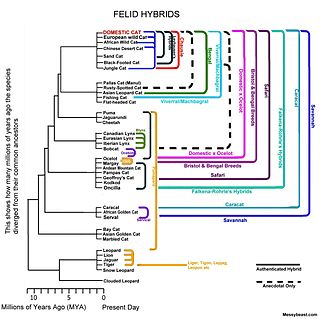

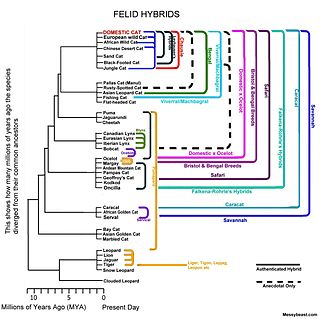

A felid hybrid is any of a number of hybrids between various species of the cat family, Felidae. This article deals with hybrids between the species of the subfamily Felinae.

The Serengeti is a hybrid breed of domestic cat, first developed by crossing a Bengal and an Oriental Shorthair. Created by biologist Karen Sausman of Kingsmark Cattery in California in 1994, the breed is still in the development stages, but the ultimate aim is to produce a cat that looks similar to a serval, without using any recent wild cat blood.

The toyger is a breed of domestic cat, the result of breeding domestic shorthaired tabbies to make them resemble a "toy tiger", as its striped coat is reminiscent of the tiger's. The breed's creator, Judy Sugden, has stated that the breed was developed in order to inspire people to care about the conservation of tigers in the wild. It was recognized for "registration only" by The International Cat Association in the early 2000s, and advanced through all requirements to be accepted as a full championship breed in 2012. There are about 20 breeders in the United States and another 15 or so in the rest of the world, as of 2012.

The LaPerm is a breed of cat. A LaPerm's fur is curly, with the tightest curls being on the throat and on the base of the ears. LaPerms come in many colors and patterns. LaPerms generally have a very affectionate personality.

A cat registry or cat breed registry, also known as a cat fancier organization, cattery federation, or cat breeders' association, is an organization that registers domestic cats of many breeds, for exhibition and for breeding lineage tracking purposes. A cat registry stores the pedigrees (genealogies) of cats, cattery names, and other details of cats; studbooks, breed descriptions, and the formal breed standards ; lists of judges qualified to judge at shows run by or affiliated with that registry, and sometimes other information. A cat registry is not the same as a breed club or breed society. Cat registries each have their own rules and usually also organize or license (sanction) cat shows. The show procedures vary widely, and awards won in one registry are not normally recognized by another. Some registries only serve breeders, while others are oriented toward pet owners and provide individual as well as cattery memberships, while yet others are federations only deal with breed clubs or even other registries as intermediaries between the organization and breeders.

A pet exotic felid, also called pet wild cat or pet non-domestic cat, is a member of the family Felidae kept as an exotic pet.

Jean Mill was an American cat breeder. Mill is best known as the founder of the Bengal cat breed: Mill successfully crossed the wild Asian leopard cat with a domestic cat, and then backcrossed the offspring through five generations to create the domestic Bengal. Mill made contributions to two other cat breeds: the Himalayan and the standardized version of the Egyptian Mau. Mill and her first husband, Robert Sugden, were involved in a precedent-setting case about the United States government's power to monitor short wave radio communications. She also authored two books on Bengal cats.