In ancient Rome, thermae and balneae were facilities for bathing. Thermae usually refers to the large imperial bath complexes, while balneae were smaller-scale facilities, public or private, that existed in great numbers throughout Rome.

The Baths of Caracalla in Rome, Italy, were the city's second largest Roman public baths, or thermae, after the Baths of Diocletian. The baths were likely built between AD 212 and 216/217, during the reigns of emperors Septimius Severus and Caracalla. They were in operation until the 530s and then fell into disuse and ruin.

The Baths of Diocletian were public baths in ancient Rome. Named after emperor Diocletian and built from 298 CE to 306 CE, they were the largest of the imperial baths. The project was originally commissioned by Maximian upon his return to Rome in the autumn of 298 and was continued after his and Diocletian's abdication under Constantius, father of Constantine.

The Baths of Titus or Thermae Titi were public baths (Thermae) built in 81 AD at Rome, by Roman emperor Titus. The baths sat at the base of the Esquiline Hill, an area of parkland and luxury estates which had been taken over by Nero for his Golden House or Domus Aurea. Titus' baths were built in haste, possibly by converting an existing or partly built bathing complex belonging to the reviled Domus Aurea. They were not particularly extensive, and the much larger Baths of Trajan were built immediately adjacent to them at the start of the next century.

The tepidarium was the warm (tepidus) bathroom of the Roman baths heated by a hypocaust or underfloor heating system. The speciality of a tepidarium is the pleasant feeling of constant radiant heat which directly affects the human body from the walls and floor.

A caldarium was a room with a hot plunge bath, used in a Roman bath complex.

In ancient Rome, the apodyterium was the primary entry in the public baths, composed of a large changing room with cubicles or shelves where citizens could store clothing and other belongings while bathing.

The Baths of Trajan were a massive thermae, a bathing and leisure complex, built in ancient Rome and dedicated under Trajan during the kalendae of July 109, shortly after the Aqua Traiana was dedicated.

A frigidarium is one of the three main bath chambers of a Roman bath or thermae, namely the cold room. It often contains a swimming pool.

The Baths of Agrippa was a structure of ancient Rome, in what is now Italy, built by Marcus Vipsanius Agrippa. It was the first of the great thermae constructed in the city, and also the first public bath.

Bathing played a major part in ancient Roman culture and society. It was one of the most common daily activities and was practiced across a wide variety of social classes. Though many contemporary cultures see bathing as a very private activity conducted in the home, bathing in Rome was a communal activity. While the extremely wealthy could afford bathing facilities in their homes, private baths were very uncommon, and most people bathed in the communal baths (thermae). In some ways, these resembled modern-day destination spas as there were facilities for a variety of activities from exercising to sunbathing to swimming and massage.

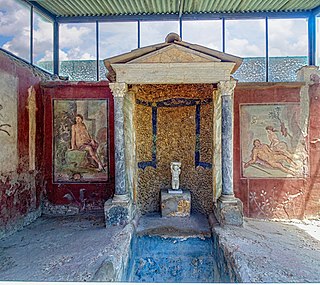

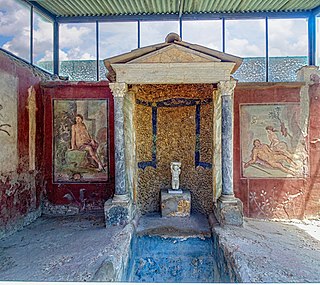

The House of Loreius Tiburtinus is renowned for well-preserved art, mainly in wall-paintings as well as its large gardens.

The Suburban Baths are a building in Pompeii, Italy, a town in the Italian region of Campania that was buried by the eruption of Mount Vesuvius in 79 AD, which consequently preserved it.

Stabiae was an ancient city situated near the modern town of Castellammare di Stabia and approximately 4.5 km southwest of Pompeii. Like Pompeii, and being only 16 km (9.9 mi) from Mount Vesuvius, this seaside resort was largely buried by tephra ash in 79 AD eruption of Mount Vesuvius, in this case at a smaller depth of up to five metres.

The Roman Baths of Ankara are the ruined remains of an ancient Roman bath complex in Ankara, Turkey, which were uncovered by excavations carried out in 1937–1944, and have subsequently been opened to the public as an open-air museum.

The Roman Thermae are a complex of Ancient Roman baths (thermae) in the Black Sea port city of Varna in northeastern Bulgaria. The Roman Thermae are situated in the southeastern part of the modern city, which under the Roman Empire was known as Odessus. The baths were constructed in the late 2nd century AD and rank as the fourth-largest preserved Roman thermae in Europe and the largest in the Balkans.

The Caliphal Baths are an Islamic bathhouse complex in Córdoba, Spain. They are situated in the historic centre which was declared a World Heritage Site by UNESCO in 1994. The complex was contiguous to the former Caliphal Palaces of the Umayyads, whose inhabitants it served. Today the baths have been partially reconstructed and are open as a museum.

The preservation and extensive excavations at Ostia Antica have brought to light 26 different bath complexes in the town. These range from large public baths, such as the Forum Baths, to smaller most likely private ones such as the small baths. It is unclear from the evidence if there was a fee charged or if they were free. Baths in Ostia would have served both a hygienic and a social function like in many other parts of the Roman world. Bath construction increased after an aqueduct was built for Ostia in the early Julio-Claudian Period. Many of the baths follow simple row arrangements, with one room following the next, due to the density of buildings in Ostia. Only a few, like the Forum Baths or the Baths of the Swimmers, had the space to include palestra. Archaeologist name the bathhouses from features preserved for example the inscription of Buticoso in building I, XIV, 8 lead to the name Bath of Buticosus or the mosaic of Neptune in building II, IV, 2 lead to the Baths of Neptune. The baths in Ostia follow the standard numbering convention by archaeologists, who divided the town into five regions, numbered I to V, and then identified the individual blocks and buildings as follows: (region) I, (block) I, (building) 1.

The Roman Ruins of Pisões, is an important Roman villa rustica located in the civil parish of Beja in the municipality of Beja, in the Portuguese Alentejo, classified as a Imóvel de Interesse Público.

The Bañuelo or El Bañuelo, also known as the Baño del Nogal or Hammam al-Yawza, is a preserved historic hammam in Granada, Spain. It is located in the Albaicin quarter of the city, on the banks of the Darro River. It was used as a bathhouse up until the 16th century at least, before becoming defunct and being converted to other uses. In the 20th century it underwent numerous restorations by Spanish experts and is now open as a tourist attraction.