Campania is an administrative region of Italy; most of it is in the south-western portion of the Italian peninsula, but it also includes the small Phlegraean Islands and the island of Capri. The capital of the Campania region is Naples. As of 2018, the region had a population of around 5,820,000 people, making it Italy's third most populous region, and, with an area of 13,590 km2 (5,247 sq mi), its most densely populated region. Based on its GDP, Campania is also the most economically productive region in southern Italy and the 7th most productive in the whole country. Naples' urban area, which is in Campania, is the eighth most populous in the European Union. The region is home to 10 of the 58 UNESCO sites in Italy, including Pompeii and Herculaneum, the Royal Palace of Caserta, the Amalfi Coast and the Historic Centre of Naples. In addition, Campania's Mount Vesuvius is part of the UNESCO World Network of Biosphere Reserves.

Cumae was the first ancient Greek colony of Magna Graecia on the mainland of Italy, founded by settlers from Euboea in the 8th century BC and soon became one of the strongest colonies. It later became a rich Roman city, the remains of which lie near the modern village of Cuma, a frazione of the comune Bacoli and Pozzuoli in the Metropolitan City of Naples, Campania, Italy.

Pozzuoli is a city and comune of the Metropolitan City of Naples, in the Italian region of Campania. It is the main city of the Phlegrean Peninsula.

Baiae was an ancient Roman town situated on the northwest shore of the Gulf of Naples and now in the comune of Bacoli. It was a fashionable resort for centuries in antiquity, particularly towards the end of the Roman Republic, when it was reckoned as superior to Capri, Pompeii, and Herculaneum by wealthy Romans, who built villas here from 100 BC. Ancient authors attest that many emperors built in Baia, almost in competition with their predecessors and they and their courts often stayed there. It was notorious for its hedonistic offerings and the attendant rumours of corruption and scandal.

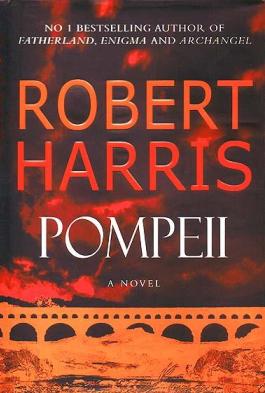

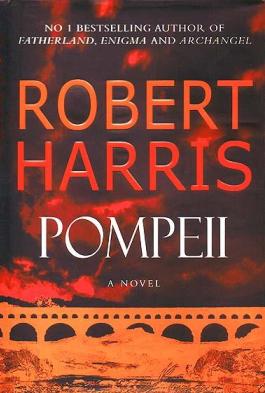

Pompeii is a novel by Robert Harris, published by Random House in 2003. It blends historical fiction with the real-life eruption of Mount Vesuvius on 24 August 79 AD, which overwhelmed the town of Pompeii and its vicinity. The novel is notable for its references to various aspects of volcanology and use of the Roman calendar. In 2007, a film version of the book had been planned and was to be directed by Roman Polanski with a budget of US$150 million, but was cancelled due to the threat of a looming actors' strike.

The Crypta Neapolitana is an ancient Roman road tunnel near Naples, Italy. It was built in 37 BC and is over 700 metres long.

Agnano is a suburb of Napoli, Italy, situated southwest of the city in the Campi Flegrei region. It was popular among both ancient Greeks and Romans and was famed for its hot sulphurous springs.

The Aqua Appia was the first Roman aqueduct, constructed in 312 BC by the co-censors Gaius Plautius Venox and Appius Claudius Caecus, the same Roman censor who also built the important Via Appia.

Posillipo is an affluent residential quarter of Naples, southern Italy, located along the northern coast of the Gulf of Naples.

The Romans constructed aqueducts throughout their Republic and later Empire, to bring water from outside sources into cities and towns. Aqueduct water supplied public baths, latrines, fountains, and private households; it also supported mining operations, milling, farms, and gardens.

Serino is a town and comune in the province of Avellino, Campania, southern Italy.

Running beneath the Italian city of Naples and the surrounding area is an underground geothermal zone and several tunnels dug during the ages. This geothermal area is present generally from Mount Vesuvius beneath a wide area including Pompei, Herculaneum, and from the volcanic area of Campi Flegrei beneath Naples and over to Pozzuoli and the coastal Baia area. Mining and various infrastructure projects during several millennia have formed extensive caves and underground structures in the zone.

The Piscina Mirabilis is an Ancient Roman cistern on the Bacoli hill at the western end of the Gulf of Naples, southern Italy. It ranks as one of the largest ancient cisterns built by the ancient Romans, compared to the largest Roman reservoir, the Yerebatan Sarayi in Istanbul.

Miseno is one of the frazioni of the municipality of Bacoli in the Italian Province of Naples. Known in ancient Roman times as Misenum, it is the site of a great Roman port.

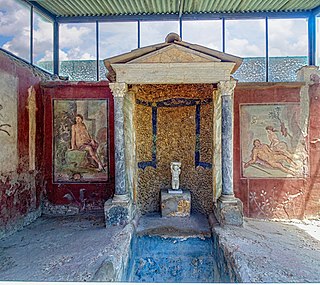

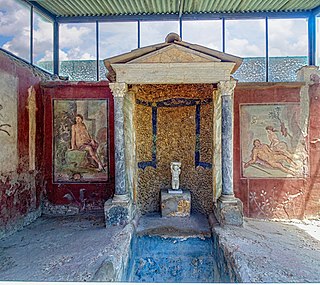

The House of Loreius Tiburtinus is renowned for well-preserved art, mainly in wall-paintings as well as its large gardens.

The Aqua Alexandrina was a Roman aqueduct located in the city of Rome. The 22.4 km long aqueduct carried water from Pantano Borghese to the Baths of Alexander on the Campus Martius. It remained in use from the 3rd to the 8th century AD.

The Aqua Marcia is one of the longest of the eleven aqueducts that supplied the city of Rome. The aqueduct was built between 144–140 BC, during the Roman Republic. The still-functioning Acqua Felice from 1586 runs on long stretches along the route of the Aqua Marcia.

The Aqua Anio Vetus was an ancient Roman aqueduct, and the second oldest after the Aqua Appia.

Naples (Italy) and its immediate surroundings preserve an archaeological heritage of inestimable value and among the best in the world. For example, the archaeological park of the Phlegraean Fields is directly connected to the centre of Naples through the Cumana railway, and the nearby sites of Pompeii, Herculaneum, Stabiae and Oplontis are among the World Heritage Sites of UNESCO.