AD 62 (LXII) was a common year starting on Friday of the Julian calendar. At the time, it was known as the Year of the Consulship of Marius and Afinius. The denomination AD 62 for this year has been used since the early medieval period, when the Anno Domini calendar era became the prevalent method in Europe for naming years.

Mount Vesuvius is a somma-stratovolcano located on the Gulf of Naples in Campania, Italy, about 9 km (5.6 mi) east of Naples and a short distance from the shore. It is one of several volcanoes forming the Campanian volcanic arc. Vesuvius consists of a large cone partially encircled by the steep rim of a summit caldera, resulting from the collapse of an earlier, much higher structure.

The volcanism of Italy is due chiefly to the presence, a short distance to the south, of the boundary between the Eurasian Plate and the African Plate. Italy is a volcanically active country, containing the only active volcanoes in mainland Europe. The lava erupted by Italy's volcanoes is thought to result from the subduction and melting of one plate below another.

The Phlegraean Fields is a large volcanic caldera situated to the west of Naples, Italy. It is part of the Campanian volcanic arc, which includes Mount Vesuvius on the east side of Naples. The Phlegraean Fields is monitored by the Vesuvius Observatory. It was declared a regional park in 2003.

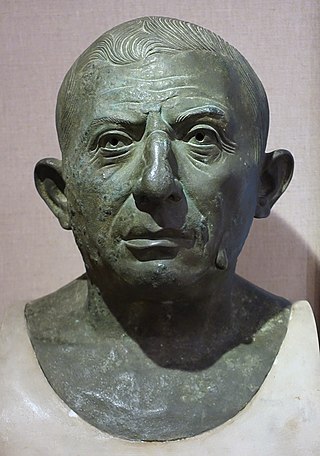

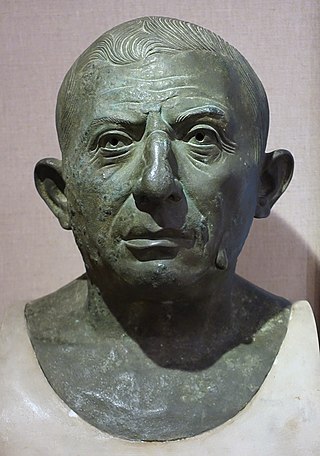

Lucius Caecilius Iucundus was a banker who lived in the Roman town of Pompeii around AD 14–62. His house still stands and can be seen in the ruins of the city of Pompeii which remain after being partially destroyed by the eruption of Vesuvius in AD 79. The house is known both for its frescoes and for the trove of wax tablets discovered there in 1875, which gave scholars access to the records of Iucundus' banking operations.

Quintus Caecilius Iucundus was the son of Lucius Caecilius Iucundus, a banker who lived in the Roman town of Pompeii around AD 14–62.

Pollena Trocchia is a comune (municipality) in the Metropolitan City of Naples in the Italian region Campania, located about 11 km east of Naples.

The ancient Roman city of Pompeii has been frequently featured in literature and popular culture since its modern rediscovery. Pompeii was buried under 4 to 6 m of volcanic ash and pumice in the eruption of Mount Vesuvius in AD 79.

Pompeii was an ancient city in what is now the comune of Pompei near Naples in the Campania region of Italy. Along with Herculaneum, Stabiae, and many surrounding villas, the city was buried under 4 to 6 m of volcanic ash and pumice in the eruption of Mount Vesuvius in 79 AD.

Herculaneum was an ancient Roman town, located in the modern-day comune of Ercolano, Campania, Italy. Herculaneum was buried under volcanic ash and pumice in the Eruption of Mount Vesuvius in 79 AD.

The 1703 Apennine earthquakes were a sequence of three earthquakes of magnitude ≥6 that occurred in the central Apennines of Italy, over a period of 19 days. The epicenters were near Norcia, Montereale and L'Aquila, showing a southwards progression over about 36 kilometres (22 mi). These events involved all of the known active faults between Norcia and L'Aquila. A total of about 10,000 people are estimated to have died as a result of these earthquakes, although because of the overlap in areas affected by the three events, casualty numbers remain highly uncertain.

The 1694 Irpinia–Basilicata earthquake occurred on 8 September. It caused widespread damage in the Basilicata and Apulia regions of what was then the Kingdom of Naples, resulting in more than 6,000 casualties. The earthquake occurred at 11:40 UTC and lasted between 30 and 60 seconds.

Of the many eruptions of Mount Vesuvius, a major stratovolcano in southern Italy, the best-known is its eruption in 79 AD, which was one of the deadliest in history.

The 1930 Senigallia earthquake struck the city of Senigallia in central Italy on 30 October. It occurred just a few months after the destructive 1930 Irpinia earthquake, which had caused over 1,400 casualties in the southern part of the country.

The 1511 Idrija earthquake occurred on March 26 with a maximum Mercalli intensity of X (Extreme). The epicenter was around the town of Idrija in present-day Slovenia, although some place it some 15-20 kilometers to the west, between Gemona and Pulfero in Friulian Slovenia. The earthquake affected a large territory between Carinthia, Friuli, present-day Slovenia and Croatia. An estimated twelve to fifteen thousand people were killed and damage was considered severe. The earthquake was felt as far as in Switzerland and present-day Slovakia. A number of castles and churches were razed to the ground in a large area from Northeastern Italy to western Croatia. Among the destroyed buildings were the castles of Udine and Škofja Loka, the monastery of the Teutonic Knights in Ljubljana; the Zagreb cathedral was severely damaged. Blaž Raškaj, commander of the Jajce fortess, in modern Bosnia, reported to the Hungarian Estates that the earthquake had severely damaged the fortifications.

The 1688 Sannio earthquake occurred in the late afternoon of June 5 in the province of Benevento of southern Italy. The moment magnitude is estimated at 7.0, with a Mercalli intensity of XI. It severely damaged numerous towns in a vast area, completely destroying Cerreto Sannita and Guardia Sanframondi. The exact number of victims is unknown, although it is estimated to total approximately 10,000. It is among the most destructive earthquakes in the history of Italy.

The 1626 Girifalco earthquake occurred on April 5 at 12:45. It was the strongest earthquake in a sequence that lasted from March 27 through to October of that year. It had an estimated magnitude of 6.0 and a maximum perceived intensity of X (Extreme) on the Modified Mercalli scale. It caused widespread destruction in Girifalco and Catanzaro, then part of the Kingdom of Naples. There is no precise estimate for the number of casualties, but it is thought to lie in the range 11–100. The earthquake may have been caused by movement on the NW-SE trending Stalettì-Squillace-Maida fault system.

The 1139 Ganja earthquake was one of the worst seismic events in history. It affected the Seljuk Empire and Kingdom of Georgia; modern-day Azerbaijan and Georgia. The earthquake had an estimated magnitude of 7.7 , 7.5 and 7.0–7.3 . A controversial death toll of 230,000–300,000 came as a consequence of this event.

The 1883 Casamicciola earthquake, also known as the Ischia earthquake occurred on 28 July at 20:25 local time on the island of Ischia in the Gulf of Naples in Italy. Although the earthquake had an estimated moment magnitude of 4.2–5.5, considered moderate in size, it caused intense ground shaking that was assigned XI (Extreme) on the Modified Mercalli intensity scale. Between 2,313 and 3,100 people lost their lives. The city also suffered great property losses, with 80 percent of all homes destroyed. This earthquake was exceptionally destructive for its magnitude mainly due to its shallow focal depth.