Cardiac arrest, also known as sudden cardiac arrest, is when the heart suddenly and unexpectedly stops beating. As a result, blood cannot properly circulate around the body and there is diminished blood flow to the brain and other organs. When the brain does not receive enough blood, this can cause a person to lose consciousness. Coma and persistent vegetative state may result from cardiac arrest. Cardiac arrest is also identified by a lack of central pulses and abnormal or absent breathing.

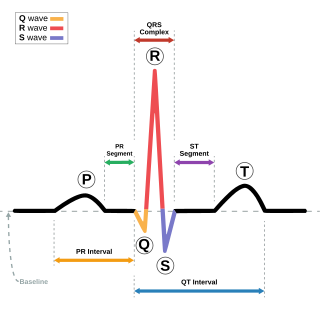

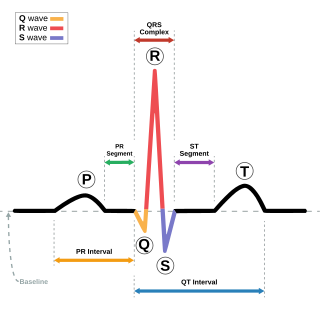

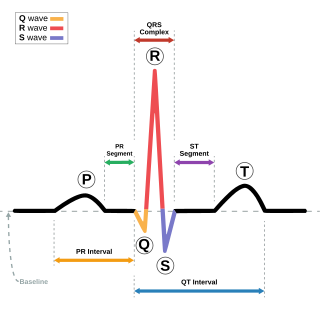

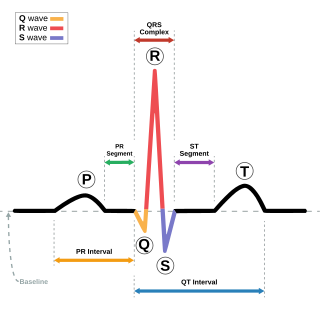

Electrocardiography is the process of producing an electrocardiogram, a recording of the heart's electrical activity through repeated cardiac cycles. It is an electrogram of the heart which is a graph of voltage versus time of the electrical activity of the heart using electrodes placed on the skin. These electrodes detect the small electrical changes that are a consequence of cardiac muscle depolarization followed by repolarization during each cardiac cycle (heartbeat). Changes in the normal ECG pattern occur in numerous cardiac abnormalities, including:

An artificial cardiac pacemaker, commonly referred to as simply a pacemaker, is an implanted medical device that generates electrical pulses delivered by electrodes to one or more of the chambers of the heart. Each pulse causes the targeted chamber(s) to contract and pump blood, thus regulating the function of the electrical conduction system of the heart.

Cardioversion is a medical procedure by which an abnormally fast heart rate (tachycardia) or other cardiac arrhythmia is converted to a normal rhythm using electricity or drugs. Synchronized electrical cardioversion uses a therapeutic dose of electric current to the heart at a specific moment in the cardiac cycle, restoring the activity of the electrical conduction system of the heart. Pharmacologic cardioversion, also called chemical cardioversion, uses antiarrhythmia medication instead of an electrical shock.

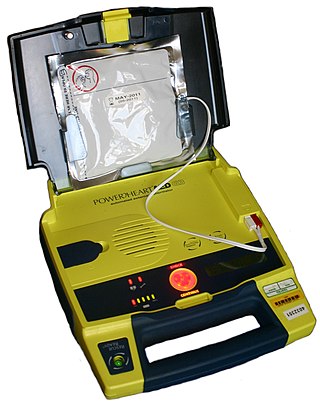

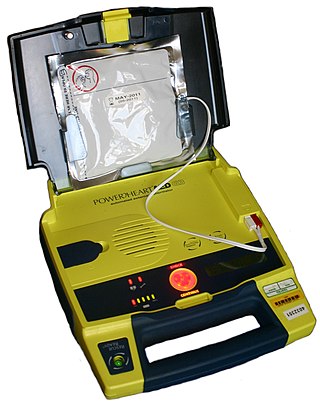

Defibrillation is a treatment for life-threatening cardiac arrhythmias, specifically ventricular fibrillation (V-Fib) and non-perfusing ventricular tachycardia (V-Tach). A defibrillator delivers a dose of electric current to the heart. Although not fully understood, this process depolarizes a large amount of the heart muscle, ending the arrhythmia. Subsequently, the body's natural pacemaker in the sinoatrial node of the heart is able to re-establish normal sinus rhythm. A heart which is in asystole (flatline) cannot be restarted by a defibrillator; it would be treated only by cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) and medication, and then by cardioversion or defibrillation if it converts into a shockable rhythm.

Tachycardia, also called tachyarrhythmia, is a heart rate that exceeds the normal resting rate. In general, a resting heart rate over 100 beats per minute is accepted as tachycardia in adults. Heart rates above the resting rate may be normal or abnormal.

Ventricular fibrillation is an abnormal heart rhythm in which the ventricles of the heart quiver. It is due to disorganized electrical activity. Ventricular fibrillation results in cardiac arrest with loss of consciousness and no pulse. This is followed by sudden cardiac death in the absence of treatment. Ventricular fibrillation is initially found in about 10% of people with cardiac arrest.

An automated external defibrillator or automatic electronic defibrillator (AED) is a portable electronic device that automatically diagnoses the life-threatening cardiac arrhythmias of ventricular fibrillation (VF) and pulseless ventricular tachycardia, and is able to treat them through defibrillation, the application of electricity which stops the arrhythmia, allowing the heart to re-establish an effective rhythm.

Wolff–Parkinson–White syndrome (WPWS) is a disorder due to a specific type of problem with the electrical system of the heart involving an accessory pathway able to conduct electrical current between the atria and the ventricles, thus bypassing the atrioventricular node. About 60% of people with the electrical problem developed symptoms, which may include an abnormally fast heartbeat, palpitations, shortness of breath, lightheadedness, or syncope. Rarely, cardiac arrest may occur. The most common type of irregular heartbeat that occurs is known as paroxysmal supraventricular tachycardia.

An implantable cardioverter-defibrillator (ICD) or automated implantable cardioverter defibrillator (AICD) is a device implantable inside the body, able to perform defibrillation, and depending on the type, cardioversion and pacing of the heart. The ICD is the first-line treatment and prophylactic therapy for patients at risk for sudden cardiac death due to ventricular fibrillation and ventricular tachycardia.

Short QT syndrome (SQT) is a very rare genetic disease of the electrical system of the heart, and is associated with an increased risk of abnormal heart rhythms and sudden cardiac death. The syndrome gets its name from a characteristic feature seen on an electrocardiogram (ECG) – a shortening of the QT interval. It is caused by mutations in genes encoding ion channels that shorten the cardiac action potential, and appears to be inherited in an autosomal dominant pattern. The condition is diagnosed using a 12-lead ECG. Short QT syndrome can be treated using an implantable cardioverter-defibrillator or medications including quinidine. Short QT syndrome was first described in 2000, and the first genetic mutation associated with the condition was identified in 2004.

Supraventricular tachycardia (SVT) is an umbrella term for fast heart rhythms arising from the upper part of the heart. This is in contrast to the other group of fast heart rhythms – ventricular tachycardia, which start within the lower chambers of the heart. There are four main types of SVT: atrial fibrillation, atrial flutter, paroxysmal supraventricular tachycardia (PSVT), and Wolff–Parkinson–White syndrome. The symptoms of SVT include palpitations, feeling of faintness, sweating, shortness of breath, and/or chest pain.

AV-nodal reentrant tachycardia (AVNRT) is a type of abnormal fast heart rhythm. It is a type of supraventricular tachycardia (SVT), meaning that it originates from a location within the heart above the bundle of His. AV nodal reentrant tachycardia is the most common regular supraventricular tachycardia. It is more common in women than men. The main symptom is palpitations. Treatment may be with specific physical maneuvers, medications, or, rarely, synchronized cardioversion. Frequent attacks may require radiofrequency ablation, in which the abnormally conducting tissue in the heart is destroyed.

Premature atrial contraction (PAC), also known as atrial premature complexes (APC) or atrial premature beats (APB), are a common cardiac dysrhythmia characterized by premature heartbeats originating in the atria. While the sinoatrial node typically regulates the heartbeat during normal sinus rhythm, PACs occur when another region of the atria depolarizes before the sinoatrial node and thus triggers a premature heartbeat, in contrast to escape beats, in which the normal sinoatrial node fails, leaving a non-nodal pacemaker to initiate a late beat.

Pediatric advanced life support (PALS) is a course offered by the American Heart Association (AHA) for health care providers who take care of children and infants in the emergency room, critical care and intensive care units in the hospital, and out of hospital. The course teaches healthcare providers how to assess injured and sick children and recognize and treat respiratory distress/failure, shock, cardiac arrest, and arrhythmias.

The following outline is provided as an overview of and topical guide to cardiology, the branch of medicine dealing with disorders of the human heart. The field includes medical diagnosis and treatment of congenital heart defects, coronary artery disease, heart failure, valvular heart disease and electrophysiology. Physicians who specialize in cardiology are called cardiologists.

Junctional ectopic tachycardia (JET) is a rare syndrome of the heart that manifests in patients recovering from heart surgery. It is characterized by cardiac arrhythmia, or irregular beating of the heart, caused by abnormal conduction from or through the atrioventricular node. In newborns and infants up to 6 weeks old, the disease may also be referred to as His bundle tachycardia or congenital JET.

A wearable cardioverter defibrillator (WCD) is a non-invasive, external device for patients at risk of sudden cardiac arrest (SCA). It allows physicians time to assess their patient's arrhythmic risk and see if their ejection fraction improves before determining the next steps in patient care. It is a leased device. A summary of the device, its technology and indications was published in 2017 and reviewed by the EHRA Scientific Documents Committee.

Arrhythmias, also known as cardiac arrhythmias, are irregularities in the heartbeat, including when it is too fast or too slow. A resting heart rate that is too fast – above 100 beats per minute in adults – is called tachycardia, and a resting heart rate that is too slow – below 60 beats per minute – is called bradycardia. Some types of arrhythmias have no symptoms. Symptoms, when present, may include palpitations or feeling a pause between heartbeats. In more serious cases, there may be lightheadedness, passing out, shortness of breath, chest pain, or decreased level of consciousness. While most cases of arrhythmia are not serious, some predispose a person to complications such as stroke or heart failure. Others may result in sudden death.

Rhythm interpretation is an important part of healthcare in Emergency Medical Services (EMS). Trained medical personnel can determine different treatment options based on the cardiac rhythm of a patient. There are many common heart rhythms that are part of a few different categories, sinus arrhythmia, atrial arrhythmia, ventricular arrhythmia. Rhythms can be evaluated by measuring a few key components of a rhythm strip, the PQRST sequence, which represents one cardiac cycle, the ventricular rate, which is the rate at which the ventricles contract, and the atrial rate, which is the rate at which the atria contract.