Related Research Articles

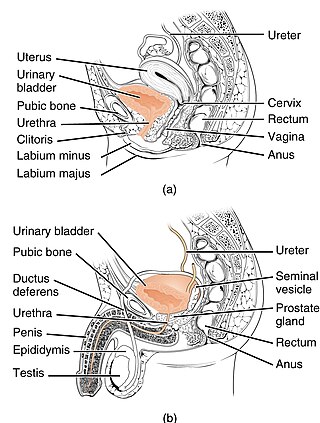

The urethra is a tube that connects the urinary bladder to the urinary meatus for the removal of urine from the body of both females and males. In human females and other primates, the urethra connects to the urinary meatus above the vagina, whereas in marsupials, the female's urethra empties into the urogenital sinus.

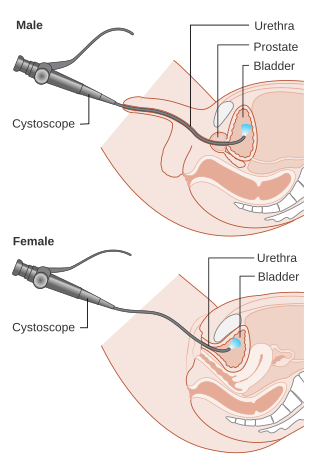

Cystoscopy is endoscopy of the urinary bladder via the urethra. It is carried out with a cystoscope.

The ureters are tubes made of smooth muscle that propel urine from the kidneys to the urinary bladder. In a human adult, the ureters are usually 20–30 cm (8–12 in) long and around 3–4 mm (0.12–0.16 in) in diameter. The ureter is lined by urothelial cells, a type of transitional epithelium, and has an additional smooth muscle layer that assists with peristalsis in its lowest third.

In urinary catheterization a latex, polyurethane, or silicone tube known as a urinary catheter is inserted into the bladder through the urethra to allow urine to drain from the bladder for collection. It may also be used to inject liquids used for treatment or diagnosis of bladder conditions. A clinician, often a nurse, usually performs the procedure, but self-catheterization is also possible. A catheter may be in place for long periods of time or removed after each use.

Hematuria or haematuria is defined as the presence of blood or red blood cells in the urine. "Gross hematuria" occurs when urine appears red, brown, or tea-colored due to the presence of blood. Hematuria may also be subtle and only detectable with a microscope or laboratory test. Blood that enters and mixes with the urine can come from any location within the urinary system, including the kidney, ureter, urinary bladder, urethra, and in men, the prostate. Common causes of hematuria include urinary tract infection (UTI), kidney stones, viral illness, trauma, bladder cancer, and exercise. These causes are grouped into glomerular and non-glomerular causes, depending on the involvement of the glomerulus of the kidney. But not all red urine is hematuria. Other substances such as certain medications and foods can cause urine to appear red. Menstruation in women may also cause the appearance of hematuria and may result in a positive urine dipstick test for hematuria. A urine dipstick test may also give an incorrect positive result for hematuria if there are other substances in the urine such as myoglobin, a protein excreted into urine during rhabdomyolysis. A positive urine dipstick test should be confirmed with microscopy, where hematuria is defined by three of more red blood cells per high power field. When hematuria is detected, a thorough history and physical examination with appropriate further evaluation can help determine the underlying cause.

Urinary retention is an inability to completely empty the bladder. Onset can be sudden or gradual. When of sudden onset, symptoms include an inability to urinate and lower abdominal pain. When of gradual onset, symptoms may include loss of bladder control, mild lower abdominal pain, and a weak urine stream. Those with long-term problems are at risk of urinary tract infections.

Hydronephrosis describes hydrostatic dilation of the renal pelvis and calyces as a result of obstruction to urine flow downstream. Alternatively, hydroureter describes the dilation of the ureter, and hydronephroureter describes the dilation of the entire upper urinary tract.

The Mitrofanoff procedure, also known as the Mitrofanoff appendicovesicostomy, is a surgical procedure in which the appendix is used to create a conduit, or channel, between the skin surface and the urinary bladder. The small opening on the skin surface, or the stoma, is typically located either in the navel or nearby the navel on the right lower side of the abdomen. Originally developed by Professor Paul Mitrofanoff in 1980, the procedure represents an alternative to urethral catheterization and is sometimes used by people with urethral damage or by those with severe autonomic dysreflexia. An intermittent catheter, or a catheter that is inserted and then removed after use, is typically passed through the channel every 3–4 hours and the urine is drained into a toilet or a bottle. As the bladder fills, rising pressure compresses the channel against the bladder wall, creating a one-way valve that prevents leakage of urine between catheterizations.

Vesicoureteral reflux (VUR), also known as vesicoureteric reflux, is a condition in which urine flows retrograde, or backward, from the bladder into one or both ureters and then to the renal calyx or kidneys. Urine normally travels in one direction from the kidneys to the bladder via the ureters, with a one-way valve at the vesicoureteral (ureteral-bladder) junction preventing backflow. The valve is formed by oblique tunneling of the distal ureter through the wall of the bladder, creating a short length of ureter (1–2 cm) that can be compressed as the bladder fills. Reflux occurs if the ureter enters the bladder without sufficient tunneling, i.e., too "end-on".

Posterior urethral valve (PUV) disorder is an obstructive developmental anomaly in the urethra and genitourinary system of male newborns. A posterior urethral valve is an obstructing membrane in the posterior male urethra as a result of abnormal in utero development. It is the most common cause of bladder outlet obstruction in male newborns. The disorder varies in degree, with mild cases presenting late due to milder symptoms. More severe cases can have renal and respiratory failure from lung underdevelopment as result of low amniotic fluid volumes, requiring intensive care and close monitoring. It occurs in about one in 8,000 babies.

Pyelogram is a form of imaging of the renal pelvis and ureter.

Neurogenic bladder dysfunction, or neurogenic bladder, refers to urinary bladder problems due to disease or injury of the central nervous system or peripheral nerves involved in the control of urination. There are multiple types of neurogenic bladder depending on the underlying cause and the symptoms. Symptoms include overactive bladder, urinary urgency, frequency, incontinence or difficulty passing urine. A range of diseases or conditions can cause neurogenic bladder including spinal cord injury, multiple sclerosis, stroke, brain injury, spina bifida, peripheral nerve damage, Parkinson's disease, or other neurodegenerative diseases. Neurogenic bladder can be diagnosed through a history and physical as well as imaging and more specialized testing. Treatment depends on underlying disease as well as symptoms and can be managed with behavioral changes, medications, surgeries, or other procedures. The symptoms of neurogenic bladder, especially incontinence, can have a significant impact on quality of life.

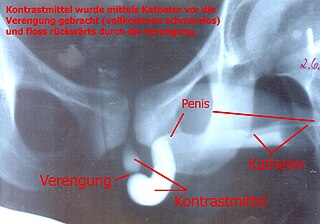

A retrograde urethrography is a routine radiologic procedure used to image the integrity of the urethra. Hence a retrograde urethrogram is essential for diagnosis of urethral injury, or urethral stricture.

Urologic diseases or conditions include urinary tract infections, kidney stones, bladder control problems, and prostate problems, among others. Some urologic conditions do not affect a person for that long and some are lifetime conditions. Kidney diseases are normally investigated and treated by nephrologists, while the specialty of urology deals with problems in the other organs. Gynecologists may deal with problems of incontinence in women.

Cystometry, also known as flow cystometry, is a clinical diagnostic procedure used to evaluate bladder function. Specifically, it measures contractile force of the bladder when voiding. The resulting chart generated from cystometric analysis is known as a cystometrogram (CMG), which plots intravesical pressure against the volume of fluid in the bladder.

In radiology and urology, a cystography is a procedure used to visualise the urinary bladder.

Urodynamic testing or urodynamics is a study that assesses how the bladder and urethra are performing their job of storing and releasing urine. Urodynamic tests can help explain symptoms such as:

Cystourethrography is a radiographic, fluoroscopic medical procedure that is used to visualize and evaluate the female urethra. Voiding and positive pressure cystourethrograms help to assess lower urinary tract trauma, reflux, suspected fistulas, and to diagnose urinary retention. Magnetic imaging (MRI) has been replacing this diagnostic tool due to its increased sensitivity. This imaging technique is used to diagnose hydronephrosis, voiding anomalies, and urinary tract infections in children. abnormalities.

The genitourinary tract, or simply the urinary tract, consists of the kidneys, ureters, bladder, and the urethra. The kidney is the most frequently injured. Injuries to the kidney commonly occur after automobile or sports-related accidents. A blunt force is involved in 80-85% of injuries. Major decelerations can result in vascular injuries near the kidney's hilum. Gunshots and knife wounds and fractured ribs can result in penetrating injuries to the kidney.

References

- 1 2 3 4 Frimberger D, Mercado-Deane MG (November 2016). "Establishing a Standard Protocol for the Voiding Cystourethrography". Pediatrics (Clinical Report). American Academy of Pediatrics. 138 (5): e20162590. doi: 10.1542/peds.2016-2590 .

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Watson N, Jones H (2018). Chapman and Nakielny's Guide to Radiological Procedures. Elsevier. pp. 138–140. ISBN 9780702071669.

- ↑ "Cystocele (Prolapsed Bladder) | NIDDK". National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases. Retrieved 2017-12-17.

- ↑ Kawashima, Akira; Sandler, Carl M.; Wasserman, Neil F.; LeRoy, Andrew J.; King, Bernard F.; Goldman, Stanford M. (October 2004). "Imaging of Urethral Disease: A Pictorial Review". RadioGraphics. 24 (suppl_1): S195–S216. doi:10.1148/rg.24si045504. ISSN 0271-5333.

- ↑ Herd DW (2008). "Anxiety in Children Undergoing VCUG: Sedation or No Sedation?". Advances in Urology (Review article). Hindawi Publishing Corporation. 2008. doi: 10.1155/2008/498614 . PMC 2443423 . Article ID 498614.

- ↑ Johnson EK, Malhotra NR, Shannon R, Jacobson DL, Green J, Rigsby CK, Holl JL, Cheng EY (August 2017). "Urinary tract infection after voiding cystourethrogram". Journal of Pediatric Urology. 13 (4): 384.e1-e7. doi:10.1016/j.jpurol.2017.04.018.(subscription required)

- ↑ Liao YH, Lin CL, Wei CC, Tsai PP, Shen WC, Sung FC, Li TC, Kao CH (30 December 2013). "Subsequent cancer risk of children receiving post voiding cystourethrography: A nationwide population-based retrospective cohort study". Pediatric Nephrology. 29 (5): 885–91. doi:10.1007/s00467-013-2703-5.(subscription required)