Human migration is the movement of people from one place to another, with intentions of settling, permanently or temporarily, at a new location. The movement often occurs over long distances and from one country to another, but internal migration is the dominant form of human migration globally.

An internally displaced person (IDP) is someone who is forced to leave their home but who remains within their country's borders. They are often referred to as refugees, although they do not fall within the legal definitions of a refugee.

Forced displacement is an involuntary or coerced movement of a person or people away from their home or home region. The UNHCR defines 'forced displacement' as follows: displaced "as a result of persecution, conflict, generalized violence or human rights violations".

Environmental degradation is the deterioration of the environment through depletion of resources such as quality of air, water and soil; the destruction of ecosystems; habitat destruction; the extinction of wildlife; and pollution. It is defined as any change or disturbance to the environment perceived to be deleterious or undesirable. The environmental degradation process amplifies the impact of environmental issues which leave lasting impacts on the environment.

Land degradation is a process where land becomes less healthy and productive due to a combination of human activities or natural conditions. The causes for land degradation are numerous and complex. Human activities are often the main cause, such as unsustainable land management practices. Natural hazards are excluded as a cause; however human activities can indirectly affect phenomena such as floods and wildfires.

Development-induced displacement and resettlement (DIDR) occurs when people are forced to leave their homes in a development-driven form of forced migration. Historically, it has been associated with the construction of dams for hydroelectric power and irrigation, but it can also result from various development projects such as mining, agriculture, the creation of military installations, airports, industrial plants, weapon testing grounds, railways, road developments, urbanization, conservation projects, and forestry.

Norman Myers was a British environmentalist specialising in biodiversity and also noted for his work on environmental refugees.

African environmental problems are problems caused by the direct and indirect human impacts on the natural environment and affect humans and nearly all forms of life in Africa. Issues include deforestation, soil degradation, air pollution, water pollution, coastal erosion, garbage pollution, climate change, Oil spills, Biodiversity loss, and water scarcity. These issues result in environmental conflict and are connected to broader social struggles for democracy and sovereignty. The scarcity of climate adaptation techniques in Africa makes it the least resilient continent to climate change.

Ghoramara Island is an island 92 km south of Kolkata, India in the Sundarban Delta complex of the Bay of Bengal. The island is small, roughly five square kilometers in area, and is quickly disappearing due to erosion and sea level rise.

The Kampala Convention is a treaty of the African Union (AU) that addresses internal displacement caused by armed conflict, natural disasters and large-scale development projects in Africa.

Climate change is a critical issue in Bangladesh. as the country is one of the most vulnerable to the effects of climate change. In the 2020 edition of Germanwatch's Climate Risk Index, it ranked seventh in the list of countries most affected by climate calamities during the period 1999–2018. Bangladesh's vulnerability to the effects of climate change is due to a combination of geographical factors, such as its flat, low-lying, and delta-exposed topography. and socio-economic factors, including its high population density, levels of poverty, and dependence on agriculture. The impacts and potential threats include sea level rise, temperature rise, food crisis, droughts, floods, and cyclones.

Human rights and climate change is a conceptual and legal framework under which international human rights and their relationship to global warming are studied, analyzed, and addressed. The framework has been employed by governments, United Nations organizations, intergovernmental and non-governmental organizations, human rights and environmental advocates, and academics to guide national and international policy on climate change under the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) and the core international human rights instruments. In 2022 Working Group II of the IPCC suggested that "climate justice comprises justice that links development and human rights to achieve a rights-based approach to addressing climate change".

Water scarcity in Iran is caused by high climatic variability, uneven distribution of water, over exploitation of available water resources,and prioritization of economic development. Water scarcity in Iran is further exacerbated by climate change.

A refugee crisis can refer to difficulties and dangerous situations in the reception of large groups of forcibly displaced persons. These could be either internally displaced, refugees, asylum seekers or any other huge groups of migrants.

The effects of climate change on small island countries are affecting people in coastal areas through sea level rise, increasing heavy rain events, tropical cyclones and storm surges. These effects of climate change threaten the existence of many island countries, their peoples and cultures. They also alter ecosystems and natural environments in those countries. Small island developing states (SIDS) are a heterogenous group of countries but many of them are particularly at risk to climate change. Those countries have been quite vocal in calling attention to the challenges they face from climate change. For example, the Maldives and nations of the Caribbean and Pacific Islands are already experiencing considerable impacts of climate change. It is critical for them to implement climate change adaptation measures fast.

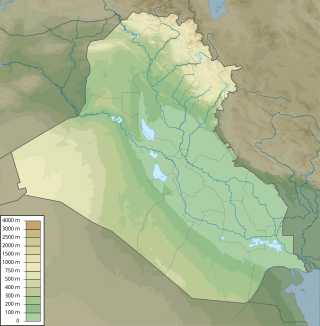

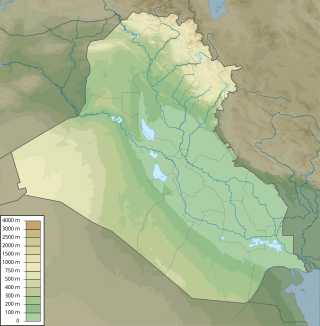

In Iraq, climate change has led to environmental impacts such as increasing temperatures, decreasing precipitation, land degradation, and water scarcity. Climate change poses numerous risks to human health, livelihoods, political stability, and the sustainable development of the nation. The combination of ecological factors, conflict, weak governance, and an impeded capacity to mitigate climate change, has made Iraq uniquely at risk to the negative effects of climate change, with the UN ranking them the 5th most vulnerable country to climate change. Rising temperatures, intensified droughts, declining precipitation, desertification, salinization, and the increasing prevalence of dust storms are challenges Iraq faces due in to the negative impacts of climate change. National and regional political instability and conflict have made it difficult to mitigate the effects of climate change, address transnational water management, and develop sustainably. Climate change has negatively impacted Iraq's population through loss of economic opportunity, food insecurity, water scarcity, and displacement.

Climate migration is a subset of climate-related mobility that refers to movement driven by the impact of sudden or gradual climate-exacerbated disasters, such as "abnormally heavy rainfalls, prolonged droughts, desertification, environmental degradation, or sea-level rise and cyclones". Gradual shifts in the environment tend to impact more people than sudden disasters. The majority of climate migrants move internally within their own countries, though a smaller number of climate-displaced people also move across national borders.

Natural disasters in Nigeria are mainly related to the climate of Nigeria, which has been reported to cause loss of lives and properties. A natural disaster might be caused by flooding, landslides, and insect infestation, among others. To be classified as a disaster, there is needs to be a profound environmental effect or human loss which must lead to financial loss. This occurrence has become an issue of concern, threatening large populations living in diverse environments in recent years.

Jane Alexandra McAdam is an Australian legal scholar, and expert in climate change and refugees. She is a Scientia Professor at the University of NSW, and is the inaugural Director of the Kaldor Centre for International Refugee Law. She was awarded an Order of Australia in 2021 for “distinguished service to international refugee law, particularly to climate change”.