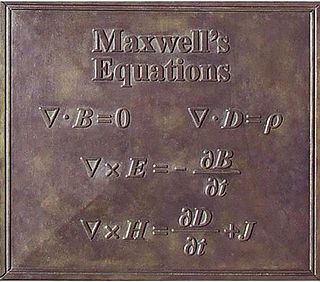

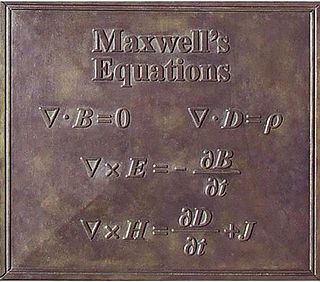

Maxwell's equations, or Maxwell–Heaviside equations, are a set of coupled partial differential equations that, together with the Lorentz force law, form the foundation of classical electromagnetism, classical optics, electric and magnetic circuits. The equations provide a mathematical model for electric, optical, and radio technologies, such as power generation, electric motors, wireless communication, lenses, radar, etc. They describe how electric and magnetic fields are generated by charges, currents, and changes of the fields. The equations are named after the physicist and mathematician James Clerk Maxwell, who, in 1861 and 1862, published an early form of the equations that included the Lorentz force law. Maxwell first used the equations to propose that light is an electromagnetic phenomenon. The modern form of the equations in their most common formulation is credited to Oliver Heaviside.

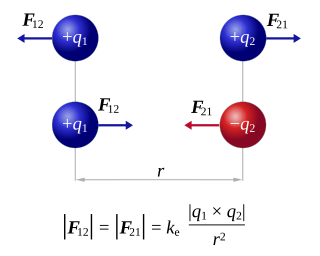

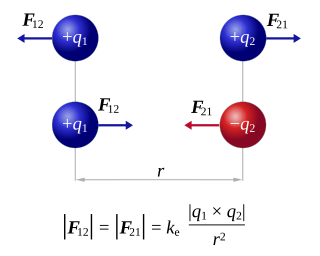

An electric field is the physical field that surrounds electrically charged particles. Charged particles exert attractive forces on each other when their charges are opposite, and repulse each other when their charges are the same. Because these forces are exerted mutually, two charges must be present for the forces to take place. The electric field of a single charge describes their capacity to exert such forces on another charged object. These forces are described by Coulomb's law, which says that the greater the magnitude of the charges, the greater the force, and the greater the distance between them, the weaker the force. Thus, we may informally say that the greater the charge of an object, the stronger its electric field. Similarly, an electric field is stronger nearer charged objects and weaker further away. Electric fields originate from electric charges and time-varying electric currents. Electric fields and magnetic fields are both manifestations of the electromagnetic field, Electromagnetism is one of the four fundamental interactions of nature.

The Navier–Stokes equations are partial differential equations which describe the motion of viscous fluid substances. They were named after French engineer and physicist Claude-Louis Navier and the Irish physicist and mathematician George Gabriel Stokes. They were developed over several decades of progressively building the theories, from 1822 (Navier) to 1842–1850 (Stokes).

Electric potential is defined as the amount of work energy needed per unit of electric charge to move the charge from a reference point to a specific point in an electric field. More precisely, the electric potential is the energy per unit charge for a test charge that is so small that the disturbance of the field under consideration is negligible. The motion across the field is supposed to proceed with negligible acceleration, so as to avoid the test charge acquiring kinetic energy or producing radiation. By definition, the electric potential at the reference point is zero units. Typically, the reference point is earth or a point at infinity, although any point can be used.

In mathematics, the Laplace operator or Laplacian is a differential operator given by the divergence of the gradient of a scalar function on Euclidean space. It is usually denoted by the symbols , (where is the nabla operator), or . In a Cartesian coordinate system, the Laplacian is given by the sum of second partial derivatives of the function with respect to each independent variable. In other coordinate systems, such as cylindrical and spherical coordinates, the Laplacian also has a useful form. Informally, the Laplacian Δf (p) of a function f at a point p measures by how much the average value of f over small spheres or balls centered at p deviates from f (p).

In physics, screening is the damping of electric fields caused by the presence of mobile charge carriers. It is an important part of the behavior of charge-carrying fluids, such as ionized gases, electrolytes, and charge carriers in electronic conductors . In a fluid, with a given permittivity ε, composed of electrically charged constituent particles, each pair of particles interact through the Coulomb force as

Poisson's equation is an elliptic partial differential equation of broad utility in theoretical physics. For example, the solution to Poisson's equation is the potential field caused by a given electric charge or mass density distribution; with the potential field known, one can then calculate electrostatic or gravitational (force) field. It is a generalization of Laplace's equation, which is also frequently seen in physics. The equation is named after French mathematician and physicist Siméon Denis Poisson.

In the calculus of variations, a field of mathematical analysis, the functional derivative relates a change in a functional to a change in a function on which the functional depends.

Electrostatics is a branch of physics that studies slow-moving or stationary electric charges.

Classical electromagnetism or classical electrodynamics is a branch of theoretical physics that studies the interactions between electric charges and currents using an extension of the classical Newtonian model. It is, therefore, a classical field theory. The theory provides a description of electromagnetic phenomena whenever the relevant length scales and field strengths are large enough that quantum mechanical effects are negligible. For small distances and low field strengths, such interactions are better described by quantum electrodynamics which is a quantum field theory.

In electromagnetism, displacement current density is the quantity ∂D/∂t appearing in Maxwell's equations that is defined in terms of the rate of change of D, the electric displacement field. Displacement current density has the same units as electric current density, and it is a source of the magnetic field just as actual current is. However it is not an electric current of moving charges, but a time-varying electric field. In physical materials, there is also a contribution from the slight motion of charges bound in atoms, called dielectric polarization.

In classical electromagnetism, polarization density is the vector field that expresses the volumetric density of permanent or induced electric dipole moments in a dielectric material. When a dielectric is placed in an external electric field, its molecules gain electric dipole moment and the dielectric is said to be polarized.

In classical electromagnetism, magnetic vector potential is the vector quantity defined so that its curl is equal to the magnetic field: . Together with the electric potential φ, the magnetic vector potential can be used to specify the electric field E as well. Therefore, many equations of electromagnetism can be written either in terms of the fields E and B, or equivalently in terms of the potentials φ and A. In more advanced theories such as quantum mechanics, most equations use potentials rather than fields.

In physics, the electric displacement field or electric induction is a vector field that appears in Maxwell's equations. It accounts for the electromagnetic effects of polarization and that of an electric field, combining the two in an auxiliary field. It plays a major role in topics such as the capacitance of a material, as well the response of dielectrics to electric field, and how shapes can change due to electric fields in piezoelectricity or flexoelectricity as well as the creation of voltages and charge transfer due to elastic strains.

A classical field theory is a physical theory that predicts how one or more fields in physics interact with matter through field equations, without considering effects of quantization; theories that incorporate quantum mechanics are called quantum field theories. In most contexts, 'classical field theory' is specifically intended to describe electromagnetism and gravitation, two of the fundamental forces of nature.

Electric potential energy is a potential energy that results from conservative Coulomb forces and is associated with the configuration of a particular set of point charges within a defined system. An object may be said to have electric potential energy by virtue of either its own electric charge or its relative position to other electrically charged objects.

In physics, charge conservation is the principle that the total electric charge in an isolated system never changes. The net quantity of electric charge, the amount of positive charge minus the amount of negative charge in the universe, is always conserved. Charge conservation, considered as a physical conservation law, implies that the change in the amount of electric charge in any volume of space is exactly equal to the amount of charge flowing into the volume minus the amount of charge flowing out of the volume. In essence, charge conservation is an accounting relationship between the amount of charge in a region and the flow of charge into and out of that region, given by a continuity equation between charge density and current density .

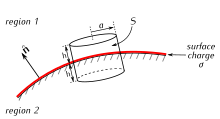

In electromagnetism, charge density is the amount of electric charge per unit length, surface area, or volume. Volume charge density is the quantity of charge per unit volume, measured in the SI system in coulombs per cubic meter (C⋅m−3), at any point in a volume. Surface charge density (σ) is the quantity of charge per unit area, measured in coulombs per square meter (C⋅m−2), at any point on a surface charge distribution on a two dimensional surface. Linear charge density (λ) is the quantity of charge per unit length, measured in coulombs per meter (C⋅m−1), at any point on a line charge distribution. Charge density can be either positive or negative, since electric charge can be either positive or negative.

There are various mathematical descriptions of the electromagnetic field that are used in the study of electromagnetism, one of the four fundamental interactions of nature. In this article, several approaches are discussed, although the equations are in terms of electric and magnetic fields, potentials, and charges with currents, generally speaking.

Coulomb's inverse-square law, or simply Coulomb's law, is an experimental law of physics that calculates the amount of force between two electrically charged particles at rest. This electric force is conventionally called the electrostatic force or Coulomb force. Although the law was known earlier, it was first published in 1785 by French physicist Charles-Augustin de Coulomb. Coulomb's law was essential to the development of the theory of electromagnetism and maybe even its starting point, as it allowed meaningful discussions of the amount of electric charge in a particle.