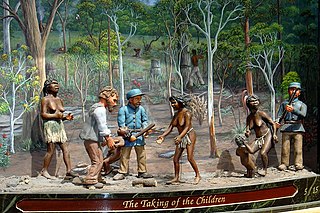

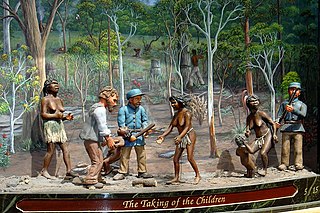

The Stolen Generations were the children of Australian Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander descent who were removed from their families by the Australian federal and state government agencies and church missions, under acts of their respective parliaments. The removals of those referred to as "half-caste" children were conducted in the period between approximately 1905 and 1967, although in some places mixed-race children were still being taken into the 1970s.

Cultural assimilation is the process in which a minority group or culture comes to resemble a society's majority group or assimilates the values, behaviors, and beliefs of another group whether fully or partially.

Keith Windschuttle is an Australian historian. He was appointed to the board of the Australian Broadcasting Corporation in 2006. He was editor of Quadrant from 2007 to 2015 when he became chair of the board and editor-in-chief. He was the publisher of Macleay Press, which operated from 1994 to 2010.

The term genocidal massacre was introduced by Leo Kuper (1908–1994) to describe incidents which have a genocidal component but are committed on a smaller scale when they are compared to genocides such as the Rwandan genocide. Others such as Robert Melson, who also makes a similar differentiation, class genocidal massacres as "partial genocide".

The history wars is a term used in Australia to describe the public debate about the interpretation of the history of the European colonisation of Australia and the development of contemporary Australian society, particularly with regard to their impact on Aboriginal Australian and Torres Strait Islander peoples. The term "history wars" emerged in the late 1990s during the term of the Howard government, and despite efforts by some of Howard's successors, the debate is ongoing, notably reignited in 2016 and 2020.

The history of Indigenous Australians began at least 65,000 years ago when humans first populated the Australian continental landmasses. This article covers the history of Aboriginal Australian and Torres Strait Islander peoples, two broadly defined groups which each include other sub-groups defined by language and culture.

Indigenous Australians are people with familial heritage from, and/or recognised membership of, the various ethnic groups living within the territory of present day Australia prior to British colonisation. They consist of two distinct groups, which includes many ethnic groups: the Aboriginal Australians of the mainland and many islands, including Tasmania, and the Torres Strait Islanders of the seas between Queensland and Papua New Guinea, located in Melanesia. The term Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples or the person's specific cultural group, is often preferred, though the terms First Nations of Australia, First Peoples of Australia and First Australians are also increasingly common; 812,728 people self-identified as being of Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander origin in the 2021 Australian Census, representing 3.2% of the total population of Australia. Of these Indigenous Australians, 91.4% identified as Aboriginal; 4.2% identified as Torres Strait Islander; while 4.4% identified with both groups. Since 1995, the Australian Aboriginal flag and the Torres Strait Islander flag have been official flags of Australia.

The Other Side of the Frontier is a history book published in 1981 by Australian historian Henry Reynolds. It is a study of Aboriginal Australian resistance to the British settlement, or invasion, of Australia from 1788 onwards.

The Australian frontier wars were the violent conflicts between Indigenous Australians and primarily British settlers during the colonial period of Australia.

Settler society is a theoretical term in the early modern period and modern history that describes a common link between modern, predominantly European, attempts to permanently settle in other areas of the world. It is used to distinguish settler colonies from resource extraction colonies. The term came to wide use in the 1970s as part of the discourse on decolonization, particularly to describe older colonial units.

The Darumbal people, also spelt Darambal and Dharumbal, are the Aboriginal Australian people who have traditionally occupied Central Queensland, speaking dialects of the Darumbal language. Darumbal people of the Keppel Islands and surrounding regions are sometimes also known as Woppaburra or Ganumi, and the terms are sometimes used interchangeably.

The genocide of Indigenous peoples, colonial genocide, or settler genocide is the intentional elimination of Indigenous peoples as a part of the process of colonialism.

Anna Elizabeth Haebich, is an Australian writer, historian and academic.

Settler colonialism occurs when colonizers and settlers invade and occupy territory to permanently replace the existing society with the society of the colonizers.

Anthony Dirk Moses is an Australian scholar who researches various aspects of genocide. In 2022 he became the Anne and Bernard Spitzer Professor of Political Science at the City College of New York, after having been the Frank Porter Graham Distinguished Professor of Global Human Rights History at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. He is a leading scholar of genocide, especially in colonial contexts, as well as of the political development of the concept itself. He is known for coining the term racial century in reference to the period 1850–1950. He is editor-in-chief of the Journal of Genocide Research.

The Karuwali are an Aboriginal Australian people of the state of Queensland.

Yued is a region inhabited by the Yued people, one of the fourteen groups of Noongar Aboriginal Australians who have lived in the South West corner of Western Australia for approximately 40,000 years.

Denial of genocides of Indigenous peoples consists of a claim that has denied any of the multiple genocides and atrocity crimes, which have been committed against Indigenous peoples. The denialism claim contradicts the academic consensus, which acknowledges that genocide was committed. The claim is a form of denialism, genocide denial, historical negationism and historical revisionism. The atrocity crimes include genocide, crimes against humanity, war crimes, and ethnic cleansing.

Peter John Read is an Australian historian specialising in the history of Indigenous Australians. Read worked as a teacher and civil servant before co-founding Link-Up. Link-Up was an organisation that reunited aboriginal families who had undergone forcible separation of children from their families through government intervention. Read coined the term "Stolen Generations" to refer to the children subject to these interventions in a 1981 study. After graduating with a doctorate, Read worked as an academic for the rest of his career primarily working on Australian Indigenous history. He has also published work on the relationship between non-indigenous Australians and the land. In 2019, Read was made a Member of the Order of Australia for his work on Indigenous history.