Mars, the fourth planet from the Sun, has appeared as a setting in works of fiction since at least the mid-1600s. Trends in the planet's portrayal have largely been influenced by advances in planetary science. It became the most popular celestial object in fiction in the late 1800s, when it became clear that there was no life on the Moon. The predominant genre depicting Mars at the time was utopian fiction. Around the same time, the mistaken belief that there are canals on Mars emerged and made its way into fiction, popularized by Percival Lowell's speculations of an ancient civilization having constructed them. The War of the Worlds, H. G. Wells's novel about an alien invasion of Earth by sinister Martians, was published in 1897 and went on to have a major influence on the science fiction genre.

An overwhelming majority of fiction is set on or features the Earth, as the only planet home to humans. This also holds true of science fiction, despite perceptions to the contrary. Works that focus specifically on Earth may do so holistically, treating the planet as one semi-biological entity. Counterfactual depictions of the shape of the Earth, be it flat or hollow, are occasionally featured. A personified, living Earth appears in a handful of works. In works set in the far future, Earth can be a center of space-faring human civilization, or just one of many inhabited planets of a galactic empire, and sometimes destroyed by ecological disaster or nuclear war or otherwise forgotten or lost.

The Moon has appeared in fiction as a setting since at least classical antiquity. Throughout most of literary history, a significant portion of works depicting lunar voyages has been satirical in nature. From the late 1800s onwards, science fiction has successively focused largely on the themes of life on the Moon, first Moon landings, and lunar colonization.

Fictional depictions of Mercury, the innermost planet of the Solar System, have gone through three distinct phases. Before much was known about the planet, it received scant attention. Later, when it was incorrectly believed that it was tidally locked with the Sun creating a permanent dayside and nightside, stories mainly focused on the conditions of the two sides and the narrow region of permanent twilight between. Since that misconception was dispelled in the 1960s, the planet has again received less attention from fiction writers, and stories have largely concentrated on the harsh environmental conditions that come from the planet's proximity to the Sun.

Mind uploading—transferring an individual's personality to a computer—appears in several works of fiction. It is distinct from the concept of transferring a consciousness from one human body to another. It is sometimes applied to a single person and other times to an entire society. Recurring themes in these stories include whether the computerized mind is truly conscious, and if so, whether identity is preserved. It is a common feature of the cyberpunk subgenre, sometimes taking the form of digital immortality.

Jupiter, the largest planet in the Solar System, has appeared in works of fiction across several centuries. The way the planet has been depicted has evolved as more has become known about its composition; it was initially portrayed as being entirely solid, later as having a high-pressure atmosphere with a solid surface underneath, and finally as being entirely gaseous. It was a popular setting during the pulp era of science fiction. Life on the planet has variously been depicted as identical to humans, larger versions of humans, and non-human. Non-human life on Jupiter has been portrayed as primitive in some works and more advanced than humans in others.

Saturn has made appearances in fiction since the 1752 novel Micromégas by Voltaire. In the earliest depictions, it was portrayed as having a solid surface rather than its actual gaseous composition. In many of these works, the planet is inhabited by aliens that are usually portrayed as being more advanced than humans. In modern science fiction, the Saturnian atmosphere sometimes hosts floating settlements. The planet is occasionally visited by humans and its rings are sometimes mined for resources.

Pluto has appeared in fiction as a setting since shortly after its 1930 discovery, albeit infrequently. It was initially comparatively popular as it was newly discovered and thought to be the outermost object of the Solar System and made more fictional appearances than either Uranus or Neptune, though still far fewer than other planets. Alien life, sometimes intelligent life and occasionally an entire ecosphere, is a common motif in fictional depictions of Pluto. Human settlement appears only sporadically, but it is often either the starting or finishing point for a tour of the Solar System. It has variously been depicted as an originally extrasolar planet, the remnants of a destroyed planet, or entirely artificial. Its moon Charon has also appeared in a handful of works.

Asteroids have appeared in fiction since at least the late 1800s, the first one—Ceres—having been discovered in 1801. They were initially only used infrequently as writers preferred the planets as settings. The once-popular Phaëton hypothesis, which states that the asteroid belt consists of the remnants of the former fifth planet that existed in an orbit between Mars and Jupiter before somehow being destroyed, has been a recurring theme with various explanations for the planet's destruction proposed. This hypothetical former planet is in science fiction often called "Bodia" in reference to Johann Elert Bode, for whom the since-discredited Titius–Bode law that predicts the planet's existence is named.

Neptune has appeared in fiction since shortly after its 1846 discovery, albeit infrequently. It initially made appearances indirectly—e.g. through its inhabitants—rather than as a setting. The earliest stories set on Neptune itself portrayed it as a rocky planet rather than as having its actual gaseous composition; later works rectified this error. Extraterrestrial life on Neptune is uncommon in fiction, though the exceptions have ranged from humanoids to gaseous lifeforms. Neptune's largest moon Triton has also appeared in fiction, especially in the late 20th century onwards.

Uranus has been used as a setting in works of fiction since shortly after its 1781 discovery, albeit infrequently. The earliest depictions portrayed it as having a solid surface, whereas later stories portrayed it more accurately as a gaseous planet. Its moons have also appeared in a handful of works. Both the planet and its moons have experienced a slight trend of increased representation in fiction over time.

In science fiction, a time viewer, temporal viewer, or chronoscope is a device that allows another point in time to be observed. The concept has appeared since the late 19th century, constituting a significant yet relatively obscure subgenre of time travel fiction and appearing in various media including literature, cinema, and television. Stories usually explain the technology by referencing cutting-edge science, though sometimes invoking the supernatural instead. Most commonly only the past can be observed, though occasionally time viewers capable of showing the future appear; these devices are sometimes limited in terms of what information about the future can be obtained. Other variations on the concept include being able to listen to the past but not view it.

The fictional portrayal of the Solar System has often included planets, moons, and other celestial objects which do not actually exist. Some of these objects were, at one time, seriously considered as hypothetical planets which were either thought to have been observed, or were hypothesized to be orbiting the Sun in order to explain certain celestial phenomena. Often such objects continued to be used in literature long after the hypotheses upon which they were based had been abandoned.

Black holes, objects whose gravity is so strong that nothing including light can escape them, have been depicted in fiction since before the term was coined by John Archibald Wheeler in the late 1960s. Black holes have been depicted with varying degrees of accuracy to the scientific understanding of them. Because what lies beyond the event horizon is unknown and by definition unobservable from outside, authors have been free to employ artistic license when depicting the interiors of black holes.

The concepts of space stations and space habitats feature in science fiction. The difference between the two is that habitats are larger and more complex structures intended as permanent homes for substantial populations, but the line between the two is fuzzy with significant overlap and the term space station is sometimes used for both concepts. The first such artificial satellite in fiction was Edward Everett Hale's "The Brick Moon" in 1869, a sphere of bricks 61 meters across accidentally launched into orbit around the Earth with people still onboard.

Supernovae have been featured in works of fiction. While a nova is strictly speaking a different type of astronomical event, science fiction writers often use the terms interchangeably and refer to stars "going nova" without further clarification; this can at least partially be explained by the earliest science fiction works featuring these phenomena predating the introduction of the term "supernova" as a separate class of event in 1934. Since these stellar explosions release enormous amounts of energy, some stories propose using them as a power source for extremely energy-intense processes, such as time travel in the Doctor Who serial The Three Doctors from 1972. For the same reason, inducing them is occasionally portrayed as a potential weapon, for instance in the 1966 novel The Solarians by Norman Spinrad.

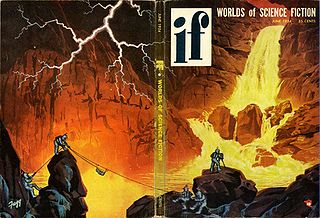

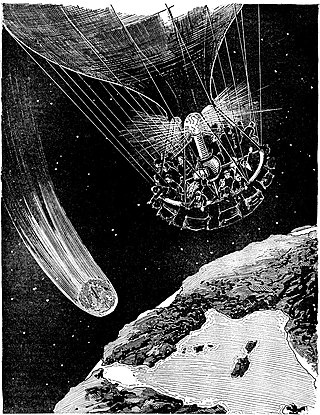

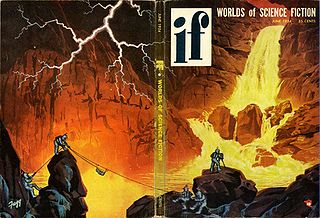

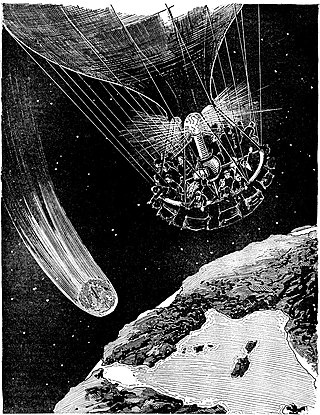

Comets have appeared in works of fiction since at least the 1830s. They primarily appear in science fiction as literal objects, but also make occasional symbolical appearances in other genres. In keeping with their traditional cultural associations as omens, they often threaten destruction to Earth. This commonly comes in the form of looming impact events, and occasionally through more novel means such as affecting Earth's atmosphere in different ways. In other stories, humans seek out and visit comets for purposes of research or resource extraction. Comets are inhabited by various forms of life ranging from microbes to vampires in different depictions, and are themselves living beings in some stories.

The far future has been used as a setting in many works of science fiction. The far future setting arose in the late 19th century, as earlier writers had little understanding of concepts such as deep time and its implications for the nature of humankind. Classic examples of this genre include works such as H.G. Wells' The Time Machine (1895) or Olaf Stapledon's Last and First Men (1930). Recurring themes include themes such as Utopias, eschatology or the ultimate fate of the universe. Many works also overlap with other genres such as space opera, science fantasy or apocalyptic and post-apocalyptic fiction.

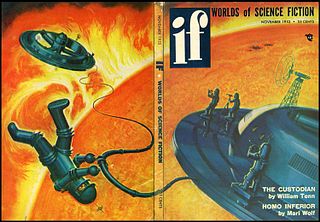

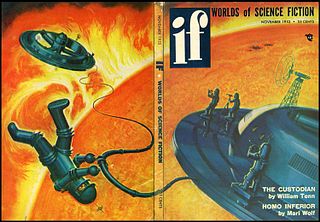

The Sun has appeared as a setting in fiction at least since classical antiquity, but for a long time it received relatively sporadic attention. Many of the early depictions viewed it as an essentially Earth-like and thus potentially habitable body—a once-common belief about celestial objects in general known as the plurality of worlds—and depicted various kinds of solar inhabitants. As more became known about the Sun through advances in astronomy, in particular its temperature, solar inhabitants fell out of favour save for the occasional more exotic alien lifeforms. Instead, many stories focused on the eventual death of the Sun and the havoc it would wreak upon life on Earth. Before it was understood that the Sun is powered by nuclear fusion, the prevailing assumption among writers was that combustion was the source of its heat and light, and it was expected to run out of fuel relatively soon. Even after the true source of the Sun's energy was discovered in the 1920s, the dimming or extinction of the Sun remained a recurring theme in disaster stories, with occasional attempts at averting disaster by reigniting the Sun. Another common way for the Sun to cause destruction is by exploding, and other mechanisms such as solar flares also appear on occasion.

Impact events have been a recurring theme in fiction since the 1800s.