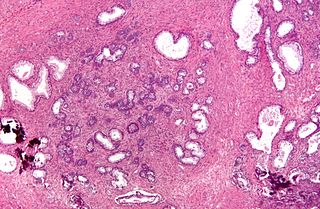

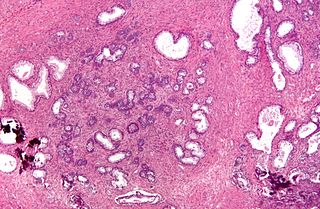

Prostate cancer is the uncontrolled growth of cells in the prostate, a gland in the male reproductive system below the bladder. Early prostate cancer causes no symptoms. Abnormal growth of prostate tissue is usually detected through screening tests, typically blood tests that check for prostate-specific antigen (PSA) levels. Those with high levels of PSA in their blood are at increased risk for developing prostate cancer. Diagnosis requires a biopsy of the prostate. If cancer is present, the pathologist assigns a Gleason score, and a higher score represents a more dangerous tumor. Medical imaging is performed to look for cancer that has spread outside the prostate. Based on the Gleason score, PSA levels, and imaging results, a cancer case is assigned a stage 1 to 4. Higher stage signifies a more advanced, more dangerous disease.

Benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH), also called prostate enlargement, is a noncancerous increase in size of the prostate gland. Symptoms may include frequent urination, trouble starting to urinate, weak stream, inability to urinate, or loss of bladder control. Complications can include urinary tract infections, bladder stones, and chronic kidney problems.

Senescence or biological aging is the gradual deterioration of functional characteristics in living organisms. The word senescence can refer to either cellular senescence or to senescence of the whole organism. Organismal senescence involves an increase in death rates and/or a decrease in fecundity with increasing age, at least in the later part of an organism's life cycle. However, the resulting effects of senescence can be delayed. The 1934 discovery that calorie restriction can extend lifespans by 50% in rats, the existence of species having negligible senescence, and the existence of potentially immortal organisms such as members of the genus Hydra have motivated research into delaying senescence and thus age-related diseases. Rare human mutations can cause accelerated aging diseases.

Urinary retention is an inability to completely empty the bladder. Onset can be sudden or gradual. When of sudden onset, symptoms include an inability to urinate and lower abdominal pain. When of gradual onset, symptoms may include loss of bladder control, mild lower abdominal pain, and a weak urine stream. Those with long-term problems are at risk of urinary tract infections.

Transurethral resection of the prostate is a urological operation. It is used to treat benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH). As the name indicates, it is performed by visualising the prostate through the urethra and removing tissue by electrocautery or sharp dissection. It has been the standard treatment for BPH for many years, but recently alternative, minimally invasive techniques have become available. This procedure is done with spinal or general anaesthetic. A triple lumen catheter is inserted through the urethra to irrigate and drain the bladder after the surgical procedure is complete. The outcome is considered excellent for 80–90% of BPH patients. The procedure carries minimal risk for erectile dysfunction, moderate risk for bleeding, and a large risk for retrograde ejaculation.

Strategies for engineered negligible senescence (SENS) is a range of proposed regenerative medical therapies, either planned or currently in development, for the periodic repair of all age-related damage to human tissue. These therapies have the ultimate aim of maintaining a state of negligible senescence in patients and postponing age-associated disease. SENS was first defined by British biogerontologist Aubrey de Grey. Many mainstream scientists believe that it is a fringe theory. De Grey later highlighted similarities and differences of SENS to subsequent categorization systems of the biology of aging, such as the highly influential Hallmarks of Aging published in 2013.

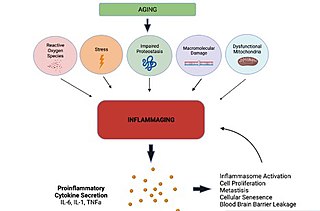

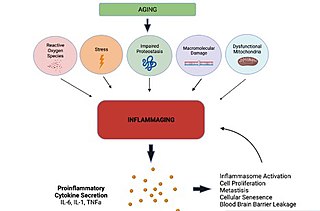

Oxidative stress reflects an imbalance between the systemic manifestation of reactive oxygen species and a biological system's ability to readily detoxify the reactive intermediates or to repair the resulting damage. Disturbances in the normal redox state of cells can cause toxic effects through the production of peroxides and free radicals that damage all components of the cell, including proteins, lipids, and DNA. Oxidative stress from oxidative metabolism causes base damage, as well as strand breaks in DNA. Base damage is mostly indirect and caused by the reactive oxygen species generated, e.g., O2− (superoxide radical), OH (hydroxyl radical) and H2O2 (hydrogen peroxide). Further, some reactive oxidative species act as cellular messengers in redox signaling. Thus, oxidative stress can cause disruptions in normal mechanisms of cellular signaling.

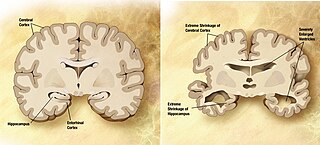

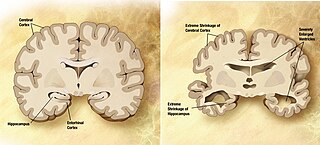

Memory disorders are the result of damage to neuroanatomical structures that hinders the storage, retention and recollection of memories. Memory disorders can be progressive, including Alzheimer's disease, or they can be immediate including disorders resulting from head injury.

A neurodegenerative disease is caused by the progressive loss of structure or function of neurons, in the process known as neurodegeneration. Such neuronal damage may ultimately involve cell death. Neurodegenerative diseases include amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, multiple sclerosis, Parkinson's disease, Alzheimer's disease, Huntington's disease, multiple system atrophy, tauopathies, and prion diseases. Neurodegeneration can be found in the brain at many different levels of neuronal circuitry, ranging from molecular to systemic. Because there is no known way to reverse the progressive degeneration of neurons, these diseases are considered to be incurable; however research has shown that the two major contributing factors to neurodegeneration are oxidative stress and inflammation. Biomedical research has revealed many similarities between these diseases at the subcellular level, including atypical protein assemblies and induced cell death. These similarities suggest that therapeutic advances against one neurodegenerative disease might ameliorate other diseases as well.

Enquiry into the evolution of ageing, or aging, aims to explain why a detrimental process such as ageing would evolve, and why there is so much variability in the lifespans of organisms. The classical theories of evolution suggest that environmental factors, such as predation, accidents, disease, and/or starvation, ensure that most organisms living in natural settings will not live until old age, and so there will be very little pressure to conserve genetic changes that increase longevity. Natural selection will instead strongly favor genes which ensure early maturation and rapid reproduction, and the selection for genetic traits which promote molecular and cellular self-maintenance will decline with age for most organisms.

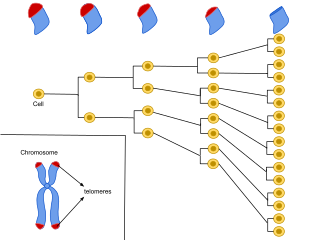

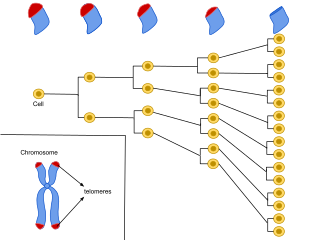

Cellular senescence is a phenomenon characterized by the cessation of cell division. In their experiments during the early 1960s, Leonard Hayflick and Paul Moorhead found that normal human fetal fibroblasts in culture reach a maximum of approximately 50 cell population doublings before becoming senescent. This process is known as "replicative senescence", or the Hayflick limit. Hayflick's discovery of mortal cells paved the path for the discovery and understanding of cellular aging molecular pathways. Cellular senescence can be initiated by a wide variety of stress inducing factors. These stress factors include both environmental and internal damaging events, abnormal cellular growth, oxidative stress, autophagy factors, among many other things.

Ageing is the process of becoming older. The term refers mainly to humans, many other animals, and fungi, whereas for example, bacteria, perennial plants and some simple animals are potentially biologically immortal. In a broader sense, ageing can refer to single cells within an organism which have ceased dividing, or to the population of a species.

Lower urinary tract symptoms (LUTS) refer to a group of clinical symptoms involving the bladder, urinary sphincter, urethra and, in men, the prostate. The term is more commonly applied to men – over 40% of older men are affected – but lower urinary tract symptoms also affect women. The condition is also termed prostatism in men, but LUTS is preferred.

The antagonistic pleiotropy hypothesis was first proposed by George C. Williams in 1957 as an evolutionary explanation for senescence. Pleiotropy is the phenomenon where one gene controls more than one phenotypic trait in an organism. A gene is considered to possess antagonistic pleiotropy if it controls more than one trait, where at least one of these traits is beneficial to the organism's fitness early on in life and at least one is detrimental to the organism's fitness later on due to a decline in the force of natural selection. The theme of G. C. William's idea about antagonistic pleiotropy was that if a gene caused both increased reproduction in early life and aging in later life, then senescence would be adaptive in evolution. For example, one study suggests that since follicular depletion in human females causes both more regular cycles in early life and loss of fertility later in life through menopause, it can be selected for by having its early benefits outweigh its late costs.

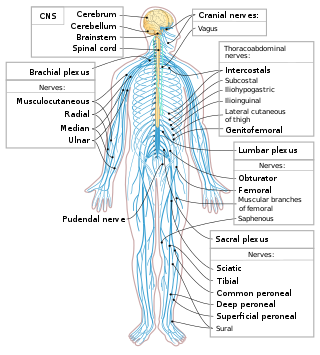

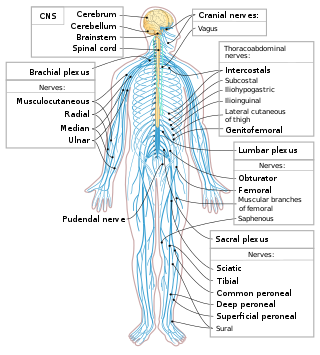

Central nervous system diseases or central nervous system disorders are a group of neurological disorders that affect the structure or function of the brain or spinal cord, which collectively form the central nervous system (CNS). These disorders may be caused by such things as infection, injury, blood clots, age related degeneration, cancer, autoimmune disfunction, and birth defects. The symptoms vary widely, as do the treatments.

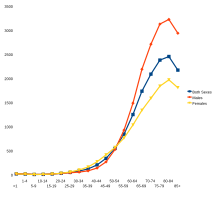

The epidemiology of cancer is the study of the factors affecting cancer, as a way to infer possible trends and causes. The study of cancer epidemiology uses epidemiological methods to find the cause of cancer and to identify and develop improved treatments.

An epigenetic clock is a biochemical test that can be used to measure age. The test is based on DNA methylation levels, measuring the accumulation of methyl groups to one's DNA molecules.

The neuroscience of aging is the study of the changes in the nervous system that occur with ageing. Aging is associated with many changes in the central nervous system, such as mild atrophy of the cortex that is considered non-pathological. Aging is also associated with many neurological and neurodegenerative disease such as amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, dementia, mild cognitive impairment, Parkinson's disease, and Creutzfeldt–Jakob disease.

Inflammaging is a chronic, sterile, low-grade inflammation that develops with advanced age, in the absence of overt infection, and may contribute to clinical manifestations of other age-related pathologies. Inflammaging is thought to be caused by a loss of control over systemic inflammation resulting in chronic overstimulation of the innate immune system. Inflammaging is a significant risk factor in mortality and morbidity in aged individuals.

Senescence-associated secretory phenotype (SASP) is a phenotype associated with senescent cells wherein those cells secrete high levels of inflammatory cytokines, immune modulators, growth factors, and proteases. SASP may also consist of exosomes and ectosomes containing enzymes, microRNA, DNA fragments, chemokines, and other bioactive factors. Soluble urokinase plasminogen activator surface receptor is part of SASP, and has been used to identify senescent cells for senolytic therapy. Initially, SASP is immunosuppressive and profibrotic, but progresses to become proinflammatory and fibrolytic. SASP is the primary cause of the detrimental effects of senescent cells.