Macon is a city in and the county seat of Macon County, Missouri, United States. The population was 5,457 at the 2020 census.

The Omaha Race Riot occurred in Omaha, Nebraska, September 28–29, 1919. The race riot resulted in the lynching of Will Brown, a black civilian; the death of two white rioters; the injuries of many Omaha Police Department officers and civilians, including the attempted hanging of Mayor Edward Parsons Smith; and a public rampage by thousands of white rioters who set fire to the Douglas County Courthouse in downtown Omaha. It followed more than 20 race riots that occurred in major industrial cities and certain rural areas of the United States during the Red Summer of 1919.

Red Summer was a period in mid-1919 during which white supremacist terrorism and racial riots occurred in more than three dozen cities across the United States, and in one rural county in Arkansas. The term "Red Summer" was coined by civil rights activist and author James Weldon Johnson, who had been employed as a field secretary by the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) since 1916. In 1919, he organized peaceful protests against the racial violence.

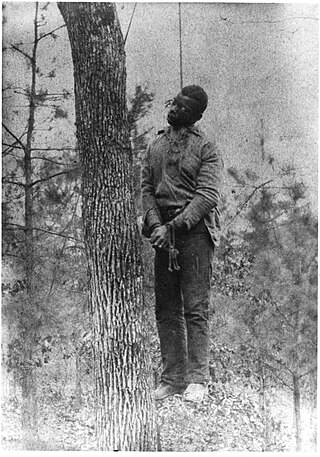

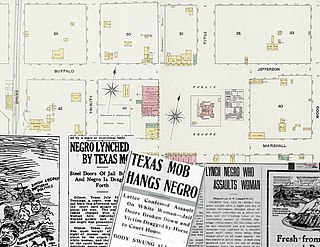

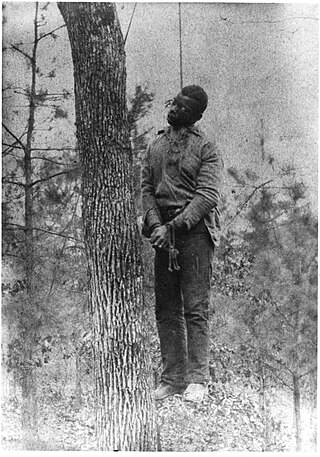

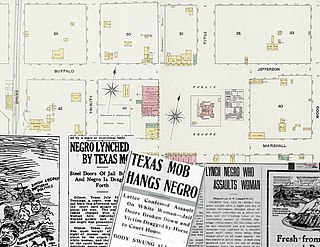

Lynching was the widespread occurrence of extrajudicial killings which began in the United States' pre–Civil War South in the 1830s and ended during the civil rights movement in the 1950s and 1960s. Although the victims of lynchings were members of various ethnicities, after roughly 4 million enslaved African Americans were emancipated, they became the primary targets of white Southerners. Lynchings in the U.S. reached their height from the 1890s to the 1920s, and they primarily victimised ethnic minorities. Most of the lynchings occurred in the American South, as the majority of African Americans lived there, but racially motivated lynchings also occurred in the Midwest and border states.

On March 19, 1906, Ed Johnson, a young African American man, was murdered by a lynch mob in his home town of Chattanooga, Tennessee. He had been sentenced to death for the rape of Nevada Taylor, but Justice John Marshall Harlan of the United States Supreme Court had issued a stay of execution. To prevent delay or avoidance of execution, a mob broke into the jail where Johnson was held, and abducted and lynched him from the Walnut Street Bridge.

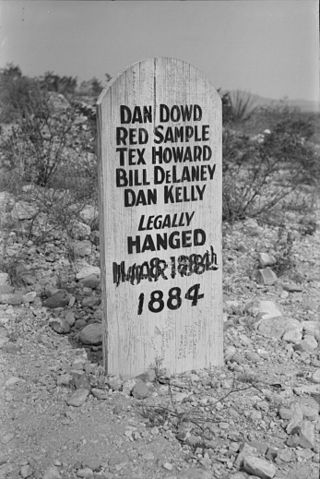

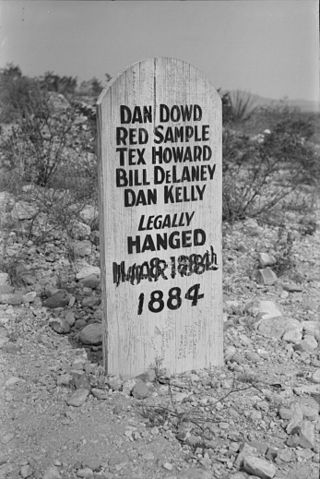

The Bisbee massacre occurred in Bisbee, Arizona, on December 8, 1883, when six outlaws who were part of the Cochise County Cowboys robbed a general store. Believing the general store's safe contained a mining payroll of $7,000, they timed the robbery incorrectly and were only able to steal between $800 and $3,000, along with a gold watch and jewelry. During the robbery, members of the gang killed five people, including a lawman and a pregnant woman. Six men were convicted of the robbery and murders. John Heath, who was accused of organizing the robbery, was tried separately and sentenced to life in prison. The other five men were convicted of murder and sentenced to hang.

Roy Mitchell was an African-American from Waco, Texas, who was convicted of six murders, and executed on July 30, 1923. His arrest, trial, conviction and execution are considered an example of continued bigotry in the Texas judicial system of the 1920s, but also of reforms aimed at curbing mob violence and public lynching. Mitchell was the last Texan to be executed in public, and is often described as the last to be legally hanged before the introduction of the electric chair.

The lynching of Marie Thompson of Shepherdsville took place in the early morning on June 15, 1904, in Lebanon Junction, Bullitt County, Kentucky, for her killing of John Irvin, a white landowner. The day before Thompson had attempted to defend her son from being beaten by Irvin in a dispute; he ordered her off the land. As she was walking away from him, he attacked her with a knife and she killed him in self-defense with a razor. She was arrested and put in the county jail.

In the early hours of 3 June 1893, a black day-laborer named Samuel J. Bush was forcibly taken from the Macon County, Illinois, jail and lynched. Mr. Bush stood accused of raping Minnie Cameron Vest, a white woman, who lived in the nearby town of Mount Zion.

Jo Reed was an African American man who was lynched in Nashville, Tennessee, on April 30, 1875, where he was taken by a white mob from the county jail after being arrested for killing a police officer in a confrontation. He was hanged from a suspension bridge but, after the rope broke, Reed survived the attempted lynching, escaped via the river, and left Nashville to go West.

Berry Washington was a 72-year-old black man who was lynched in Milan, Georgia, in 1919. He was in jail after killing a white man who was attacking two young girls. He was taken from jail and lynched by a mob.

African-American man, Jordan Jameson was lynched on November 11, 1919, in the town square of Magnolia, Columbia County, Arkansas. A large white mob seized Jameson after he allegedly shot the local sheriff. They tied him to a stake and burned him alive.

On Sunday, November 16, 1919, four African-Americans were lynched in Moberly, Missouri. Three were able to escape but one was shot to death.

Chilton Jennings was lynched on July 24, 1919, after being accused of attacking a white woman, Mrs. Virgie Haggard in Gilmer, Texas.

African Americans Irving "Ervie" Arthur (1903–1920) and his brother Herman Arthur (1892–1920), a World War I veteran, were lynched—burned alive—at the Lamar County Fairgrounds in Paris, Texas, on July 6, 1920. The event extended and amplified regional and national flashpoints for justice. It happened just a year after the racial violence of 1919's Red Summer. The family was attacked by some of the town's white population and were forced to flee to the north, mostly settling in Chicago. This and other attacks on Black Americans encouraged civil rights groups to fight against lynchings in America. Media outlets reported on the 100-year-old anniversary but the memorial events were scaled down due to the COVID-19 pandemic.

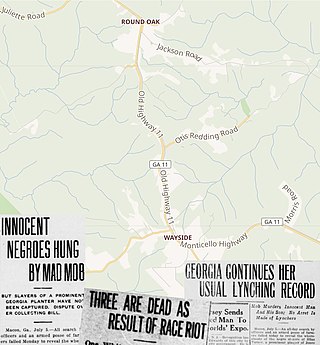

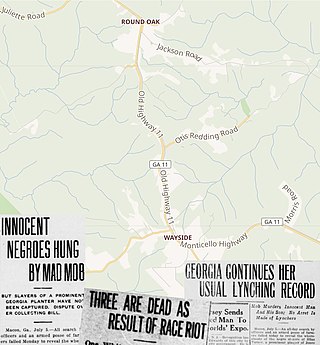

Father and son Alonzo and James D. Green were innocent African-Americans lynched near Round Oak and Wayside, Jones County, Georgia in retaliation for the murder of popular white farmer Silas Hardin Turner on July 4, 1915. A third man, William Bostick was also lynched on this day. None of those killed received a trial.

William Keemer was the victim of a racial terror spectacle lynching in 1875 in Greenfield, Indiana. Keemer, a Black man, was dragged from his jail cell in Hancock County, Indiana on June 25, 1875 by a white mob from Hancock, Shelby, and Rush counties. Keemer was hung at the Hancock County fairgrounds and over 1,000 people traveled to view the body. Keemer was arrested on June 24 for an alleged sexual assault against a white women in Carthage, Indiana. No trial was held for the alleged crime and William Keemer remains innocent. In 2021 a historical marker commemorating the anti-Black violence committed against Keemer was approved by the Indiana Historical Bureau.

The Seminole burning was the lynching by live burning of two Seminole youth, Lincoln McGeisey and Palmer Sampson, near Maud, Oklahoma, on January 8, 1898.