Mass racial violence in the United States, includes ethnic conflict and race riots, can include such events as:

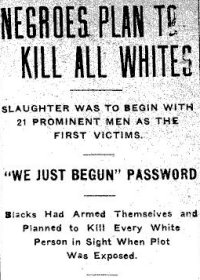

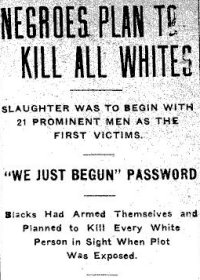

The Elaine massacre occurred on September 30–October 1, 1919 at Hoop Spur in the vicinity of Elaine in rural Phillips County, Arkansas. As many as several hundred African Americans and five white men were killed. Estimates of deaths made in the immediate aftermath of the Elaine Massacre by eyewitnesses range from 50 to "more than a hundred". Walter Francis White, an NAACP attorney who visited Elaine shortly after the incident, stated "... twenty-five Negroes killed, although some place the Negro fatalities as high as one hundred". More recent estimates in the 21st century of the number of black people killed during this violence are higher than estimates provided by the eyewitnesses, and have ranged into the hundreds. Robert Whitaker estimated 856 people were killed in his 2008 book on this topic. The white mobs were aided by federal troops and terrorist organizations such as the newly revived Ku Klux Klan. Gov. Brough led a contingent of 583 US soldiers from Camp Pike, with a 12-gun machine gun battalion.

The Omaha Race Riot occurred in Omaha, Nebraska, September 28–29, 1919. The race riot resulted in the lynching of Will Brown, a black civilian; the death of two white rioters; the injuries of many Omaha Police Department officers and civilians, including the attempted hanging of Mayor Edward Parsons Smith; and a public rampage by thousands of white rioters who set fire to the Douglas County Courthouse in downtown Omaha. It followed more than 20 race riots that occurred in major industrial cities of the United States during the Red Summer of 1919.

Red Summer was a period in mid-1919 during which white supremacist terrorism and racial riots occurred in more than three dozen cities across the United States, and in one rural county in Arkansas. The term "Red Summer" was coined by civil rights activist and author James Weldon Johnson, who had been employed as a field secretary by the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) since 1916. In 1919, he organized peaceful protests against the racial violence.

The 1991 Washington, D.C. riot, sometimes referred to as the Mount Pleasant riot or Mount Pleasant Disturbance, occurred in May 1991, when rioting broke out in the Mount Pleasant neighborhood of Washington, D.C. in response to an African-American female police officer having shot a Salvadoran man in the chest following a Cinco de Mayo celebration.

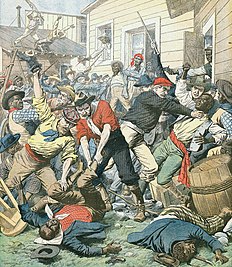

The Springfield race riot of 1908 consisted of events of mass racial violence committed against African Americans by a mob of about 5,000 white Americans and European immigrants in Springfield, Illinois, between August 14 and 16, 1908. Two black men had been arrested as suspects in a rape, and attempted rape and murder. The alleged victims were two young white women and the father of one of them. When a mob seeking to lynch the men discovered the sheriff had transferred them out of the city, the whites furiously spread out to attack black neighborhoods, murdered black citizens on the streets, and destroyed black businesses and homes. The state militia was called out to quell the rioting.

On May 16, 1918, a plantation owner was murdered, prompting a manhunt which resulted in a series of lynchings in May 1918 in southern Georgia, United States. White people killed at least 13 black people during the next two weeks. Among those killed were Hayes and Mary Turner. Hayes was killed on May 18, and the next day, his pregnant wife Mary was strung up by her feet, doused with gasoline and oil then set on fire. Mary's unborn child was cut from her abdomen and stomped to death. Her body was then repeatedly shot. No one was ever convicted of her lynching.

From 1967 to 1973, an extended period of racial unrest occurred in the town of Cairo, Illinois. The city had long had racial tensions which boiled over after a black soldier was found hanged in his jail cell. Over the next several years, fire bombings, racially charged boycotts and shootouts were common place in Cairo, with 170 nights of gunfire reported in 1969 alone.

The Knoxville riot of 1919 was a race riot that took place in the American city of Knoxville, Tennessee, on August 30–31, 1919. The riot began when a lynch mob stormed the county jail in search of Maurice Mays, a biracial man who had been accused of murdering a white woman. Unable to find Mays, the rioters looted the jail and fought a pitched gun battle with the residents of a predominantly black neighborhood. The Tennessee National Guard, which at one point fired two machine guns indiscriminately into this neighborhood, eventually dispersed the rioters. At the end of August 1919 the Great Falls Daily Tribune reported four killed in a "race war riot" while the Washington Times reported "Scores dead." Other newspapers placed the death toll at just two, though eyewitness accounts suggest it was much higher.

Claude Neal was a 23-year-old African-American farmhand who was arrested in Jackson County, Florida, on October 19, 1934, for allegedly raping and killing Lola Cannady, a 19-year-old white woman missing since the preceding night. Circumstantial evidence was collected against him, but nothing directly linked him to the crime. When the news got out about his arrest, white lynch mobs began to form. In order to keep Neal safe, County Sheriff Flake Chambliss moved him between multiple jails, including the county jail at Brewton, Alabama, 100 miles (160 km) away. But a lynch mob of about 100 white men from Jackson County heard where he was, and brought him back to Jackson County.

The Perry massacre was a racially motivated conflict in Perry, Florida, in December 1922. Whites killed four black men, including Charles Wright, who was lynched by being burned at the stake, and they also destroyed several buildings in the black community of Perry after the murder of Ruby Hendry, a white female schoolteacher.

George Armwood was lynched in Princess Anne, Maryland, on October 18, 1933. His murder was the last recorded lynching in Maryland.

The Washington race riot of 1919 was civil unrest in Washington, D.C. from July 19, 1919, to July 24, 1919. Starting July 19, white men, many in the armed forces, responded to the rumored arrest of a black man for rape of a white woman with four days of mob violence against black individuals and businesses. They rioted, randomly beat black people on the street, and pulled others off streetcars for attacks. When police refused to intervene, the black population fought back. The city closed saloons and theaters to discourage assemblies. Meanwhile, the four white-owned local papers, including the Washington Post, fanned the violence with incendiary headlines and calling in at least one instance for mobilization of a "clean-up" operation. After four days of police inaction, President Woodrow Wilson ordered 2,000 federal troops to regain control in the nation's capital. But a violent summer rainstorm had more of a dampening effect. When the violence ended, 15 people had died: at least 10 white people, including two police officers; and around 5 black people. Fifty people were seriously wounded and another 100 less severely wounded. It was one of the few times in 20th-century riots of whites against blacks that white fatalities outnumbered those of black people. The unrest was also one of the Red Summer riots in America.

Berry Washington was a 72 year old black man who was lynched in Milan, Georgia, in 1919. He was in jail after killing a white man who was attacking two young girls. He was taken from jail and lynched by a mob.

The Newberry 1919 lynching attempt was the attempted lynching of Elisha Harper, Newberry, South Carolina on July 24, 1919. Harper was sent to jail for insulting a 14 year-old girl.

African-American man, Jordan Jameson was lynched on November 11, 1919, in the town square of Magnolia, Columbia County, Arkansas. A large white mob seized Jameson after he allegedly shot the local sheriff. They tied him to a stake and burned him alive.

On December 26, 1920, an African-American man named Wade Thomas was lynched in Jonesboro, Arkansas, by a white mob. The mob seized Thomas from the Jonesboro jail after he allegedly shot local Patrolman Elmer Ragland, and murdered him.

The lynching of Henry Lowry, on January 26, 1921, was the murder of an African-American man, Henry Lowry, by a mob of white vigilantes in Arkansas. Lowry, a tenant farmer, had been on the run after a deadly shootout at the house of planter O. T. Craig on Christmas Day of 1920. Lowry went into hiding in El Paso, Texas; when he was discovered and extradited by train, a group of armed white men boarded the train in Sardis, Mississippi, and took Lowry to Nodena, near Wilson, Arkansas. He was doused in gasoline and burned alive before a mob of 500. A reporter from the Memphis Press witnessed the event, and word of the lynching soon spread around the country, aided by an article William Pickens wrote for The Nation, in which he described eastern Arkansas as "the American Congo".

Leonard Woods was an African-American man who was lynched by a mob in Pound Gap, on the border between Kentucky and Virginia, after they broke him out of jail in Whitesburg, Kentucky, on November 30, 1927. Woods was alleged to have killed the foreman of a mine, Herschel Deaton. A mob of people from Kentucky and Virginia took him from the jail and away from town and hanged him, and riddled his body with shots. The killing, which became widely publicized, was the last in a long line of extrajudicial murders in the area, and, prompted by the activism of Louis Isaac Jaffe and others, resulted in the adoption of strong anti-lynching legislation in Virginia.

18-year-old William Turner was lynched on November 18, 1921, for an alleged assault on a 15-year-old white girl. Two years earlier hundreds of African-Americans were killed during the Elaine Race Riot in Hoop Spur a nearby community also in Phillips County, Arkansas.