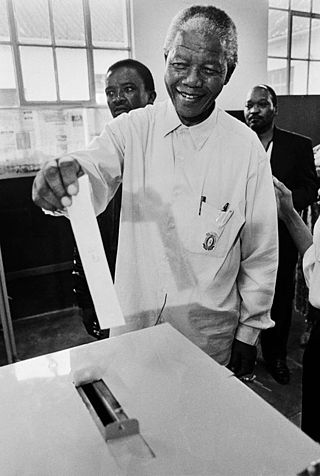

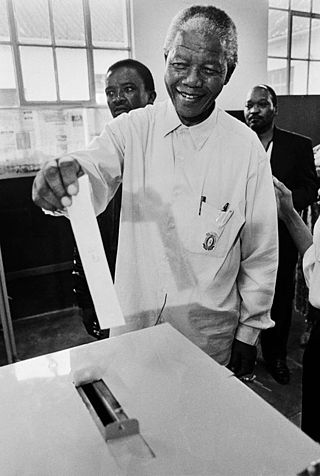

Democracy is a system of government in which state power is vested in the people or the general population of a state. According to the United Nations, democracy "provides an environment that respects human rights and fundamental freedoms, and in which the freely expressed will of people is exercised."

Politics is the set of activities that are associated with making decisions in groups, or other forms of power relations among individuals, such as the distribution of resources or status. The branch of social science that studies politics and government is referred to as political science.

Representative democracy, also known as indirect democracy, is a type of democracy where elected delegates represent a group of people, in contrast to direct democracy. Nearly all modern Western-style democracies function as some type of representative democracy: for example, the United Kingdom, Germany, France, and the United States. Representative democracy places power in the hands of representatives who are elected by the people. Political parties often become central to this form of democracy if electoral systems require or encourage voters to vote for political parties or for candidates associated with political parties. Some political theorists have described representative democracy as polyarchy.

Deliberative democracy or discursive democracy is a form of democracy in which deliberation is central to decision-making. Deliberative democracy seeks quality over quantity by limiting decision-makers to a smaller but more representative sample of the population that is given the time and resources to focus on one issue.

Participatory democracy, participant democracy or participative democracy is a form of government in which citizens participate individually and directly in political decisions and policies that affect their lives, rather than through elected representatives. Elements of direct and representative democracy are combined in this model.

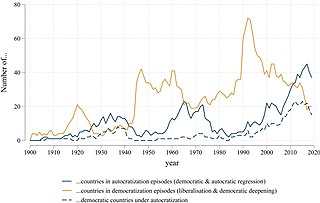

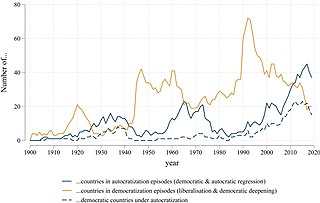

Democratization, or democratisation, is the democratic transition to a more democratic political regime, including substantive political changes moving in a democratic direction.

E-democracy, also known as digital democracy or Internet democracy, uses information and communication technology (ICT) in political and governance processes. The term is credited to digital activist Steven Clift. By using 21st-century ICT, e-democracy seeks to enhance democracy, including aspects like civic technology and E-government. Proponents argue that by promoting transparency in decision-making processes, e-democracy can empower all citizens to observe and understand the proceedings. Also, if they possess overlooked data, perspectives, or opinions, they can contribute meaningfully. This contribution extends beyond mere informal disconnected debate; it facilitates citizen engagement in the proposal, development, and actual creation of a country's laws. In this way, e-democracy has the potential to incorporate crowdsourced analysis more directly into the policy-making process.

Democratic globalization is a social movement towards an institutional system of global democracy. One of its proponents is the British political thinker David Held. In the last decade, Held published a dozen books regarding the spread of democracy from territorially defined nation states to a system of global governance that encapsulates the entire world. For some, democratic mundialisation is a variant of democratic globalisation stressing the need for the direct election of world leaders and members of global institutions by citizens worldwide; for others, it is just another name for democratic globalisation.

Robert Alan Dahl was an American political theorist and Sterling Professor of Political Science at Yale University.

Media democracy is a democratic approach to media studies that advocates for the reform of mass media to strengthen public service broadcasting and develop participation in alternative media and citizen journalism in order to create a mass media system that informs and empowers all members of society and enhances democratic values.

Noocracy where nous means 'wise' and kratos means 'rule' therefore 'rule of the wise' ) is a form of government where decision making is done by wise people. The idea is proposed by various philosophers such as Plato, Gautama Buddha, al-Farabi and Confucius.

In social sciences, participation inequality consists of difference between levels of participation of various groups in certain activities. Common examples include:

Cosmopolitan democracy is a political theory which explores the application of norms and values of democracy at the transnational and global sphere. It argues that global governance of the people, by the people, for the people is possible and needed. Writers advocating cosmopolitan democracy include Immanuel Kant, David Held, Daniele Archibugi, Richard Falk, and Mary Kaldor. In the cosmopolitan democracy model, decisions are made by those affected, avoiding a single hierarchical form of authority. According to the nature of the issues at stake, democratic practice should be reinvented to take into account the will of stakeholders. This can be done either through direct participation or through elected representatives. The model advocated by cosmopolitan democrats is confederal and decentralized—global governance without world government—unlike those models of global governance supported by classic World Federalism thinkers, such as Albert Einstein.

Liberal democracy, substantive democracy or western democracy is a form of government that combines the structure of a representative democracy with the principles of liberal political philosophy. It is characterized by elections between multiple distinct political parties, a separation of powers into different branches of government, the rule of law in everyday life as part of an open society, a market economy with private property, universal suffrage, and the equal protection of human rights, civil rights, civil liberties and political freedoms for all people. To define the system in practice, liberal democracies often draw upon a constitution, either codified or uncodified, to delineate the powers of government and enshrine the social contract. The purpose of a constitution is often seen as a limit on the authority of the government.

Voting rights of United States citizens who live in Puerto Rico, like the voting rights of residents of other United States territories, differ from those of United States citizens in each of the fifty states and the District of Columbia. Residents of Puerto Rico and other U.S. territories do not have voting representation in the United States Congress, and are not entitled to electoral votes for president. The United States Constitution grants congressional voting representation to U.S. states, which Puerto Rico and other U.S. territories are not, specifying that members of Congress shall be elected by direct popular vote and that the president and the vice president shall be elected by electors chosen by the states.

In governance, sortition is the selection of public officials or jurors using a random representative sample. This minimizes factionalism, since those selected to serve can prioritize deliberating on the policy decisions in front of them instead of campaigning. In ancient Athenian democracy, sortition was the traditional and primary method for appointing political officials, and its use was regarded as a principal characteristic of democracy.

Criticism of democracy has been a key part of democracy and its functions. As Josiah Ober explains, "the legitimate role of critics" of democracy may be difficult to define, but one "approach is to divide critics into 'good internal' critics and 'bad external' critics who reject the values embraced and nurtured by constitutional democracy".

Types of democracy refers to pluralism of governing structures such as governments and other constructs like workplaces, families, community associations, and so forth. Types of democracy can cluster around values. For example, some like direct democracy, electronic democracy, participatory democracy, real democracy, and deliberative democracy, strive to allow people to participate equally and directly in protest, discussion, decision-making, or other acts of politics. Different types of democracy - like representative democracy - strive for indirect participation as this procedural approach to collective self-governance is still widely considered the only means for the more or less stable democratic functioning of mass societies. Types of democracy can be found across time, space, and language. In the English language the noun "democracy" has been modified by 2,234 adjectives. These adjectival pairings, like atomic democracy or Zulu democracy, act as signal words that point not only to specific meanings of democracy but to groups, or families, of meaning as well.

Embedded democracy is a form of government in which democratic governance is secured by democratic partial regimes. The term "embedded democracy" was coined by political scientists Wolfgang Merkel, Hans-Jürgen Puhle, and Aurel Croissant, who identified "five interdependent partial regimes" necessary for an embedded democracy: electoral regime, political participation, civil rights, horizontal accountability, and the power of the elected representatives to govern. The five internal regimes work together to check the power of the government, while external regimes also help to secure and stabilize embedded democracies. Together, all the regimes ensure that an embedded democracy is guided by the three fundamental principles of freedom, equality, and control.

The following outline is provided as an overview of and topical guide to democracy.