In linguistics, syntax is the set of rules, principles, and processes that govern the structure of sentences in a given language, usually including word order. The term syntax is also used to refer to the study of such principles and processes. The goal of many syntacticians is to discover the syntactic rules common to all languages.

In everyday speech, a phrase is any group of words, often carrying a special idiomatic meaning; in this sense it is synonymous with expression. In linguistic analysis, a phrase is a group of words that functions as a constituent in the syntax of a sentence, a single unit within a grammatical hierarchy. A phrase typically appears within a clause, but it is possible also for a phrase to be a clause or to contain a clause within it. There are also types of phrases like noun phrase and prepositional phrase.

A noun phrase, or nominal (phrase), is a phrase that has a noun as its head or performs the same grammatical function as a noun. Noun phrases are very common cross-linguistically, and they may be the most frequently occurring phrase type.

In linguistics, X-bar theory is a theory of syntactic category formation. It embodies two independent claims: one, that phrases may contain intermediate constituents projected from a head X; and two, that this system of projected constituency may be common to more than one category.

In linguistics, branching refers to the shape of the parse trees that represent the structure of sentences. Assuming that the language is being written or transcribed from left to right, parse trees that grow down and to the right are right-branching, and parse trees that grow down and to the left are left-branching. The direction of branching reflects the position of heads in phrases, and in this regard, right-branching structures are head-initial, whereas left-branching structures are head-final. English has both right-branching (head-initial) and left-branching (head-final) structures, although it is more right-branching than left-branching. Some languages such as Japanese and Turkish are almost fully left-branching (head-final). Some languages are mostly right-branching (head-initial).

Dependency grammar (DG) is a class of modern grammatical theories that are all based on the dependency relation and that can be traced back primarily to the work of Lucien Tesnière. Dependency is the notion that linguistic units, e.g. words, are connected to each other by directed links. The (finite) verb is taken to be the structural center of clause structure. All other syntactic units (words) are either directly or indirectly connected to the verb in terms of the directed links, which are called dependencies. DGs are distinct from phrase structure grammars, since DGs lack phrasal nodes, although they acknowledge phrases. A dependency structure is determined by the relation between a word and its dependents. Dependency structures are flatter than phrase structures in part because they lack a finite verb phrase constituent, and they are thus well suited for the analysis of languages with free word order, such as Czech or Warlpiri.

In linguistics, wh-movement concerns rules of syntax involving the placement of interrogative words. In plain terms, it refers to an asymmetry between the syntactical arrangement of words or morphemes in a question and the form of answers to that question; specifically, the placement of the question word. An example in English is "What are you doing?", a response to which could be "I am editing Wikipedia."; in which the answer is at the end of the sentence but the question word (What) is at the beginning.

In generative grammar, non-configurational languages are languages characterized by a flat phrase structure, which allows syntactically discontinuous expressions, and a relatively free word order.

Topicalization is a mechanism of syntax that establishes an expression as the sentence or clause topic by having it appear at the front of the sentence or clause. Topicalization often results in a discontinuity and is thus one of a number of established discontinuity types. Topicalization is also used as a constituency test; an expression that can be topicalized is deemed a constituent. The topicalization of arguments in English is rare, whereas circumstantial adjuncts are often topicalized. Most languages allow topicalization, and in some languages, topicalization occurs much more frequently and/or in a much less marked manner than in English. Topicalization in English has also received attention in the pragmatics literature.

In linguistics, antisymmetry is a theory of syntactic linearization presented in Richard Kayne's 1994 monograph The Antisymmetry of Syntax. The crux of this theory is that hierarchical structure in natural language maps universally onto a particular surface linearization, namely specifier-head-complement branching order. The theory derives a version of X-bar theory. Kayne hypothesizes that all phrases whose surface order is not specifier-head-complement have undergone movements that disrupt this underlying order. Subsequently, there have also been attempts at deriving specifier-complement-head as the basic word order.

In linguistics, head directionality is a proposed parameter that classifies languages according to whether they are head-initial or head-final. The head is the element that determines the category of a phrase: for example, in a verb phrase, the head is a verb.

In linguistics, a small clause consists of a subject and its predicate, but lacks an overt expression of tense. Small clauses have the semantic subject-predicate characteristics of a clause, and have some, but not all, the properties of a constituent. Structural analyses of small clauses vary according to whether a flat or layered analysis is pursued. The small clause is related to the phenomena of raising-to-object, exceptional case-marking, accusativus cum infinitivo, and object control.

Exceptional case-marking (ECM), in linguistics, is a phenomenon in which the subject of an embedded infinitival verb seems to appear in a superordinate clause and, if it is a pronoun, is unexpectedly marked with object case morphology. The unexpected object case morphology is deemed "exceptional". The term ECM itself was coined in the Government and Binding grammar framework although the phenomenon is closely related to the accusativus cum infinitivo constructions of Latin. ECM-constructions are also studied within the context of raising. The verbs that license ECM are known as raising-to-object verbs. Many languages lack ECM-predicates, and even in English, the number of ECM-verbs is small. The structural analysis of ECM-constructions varies in part according to whether one pursues a relatively flat structure or a more layered one.

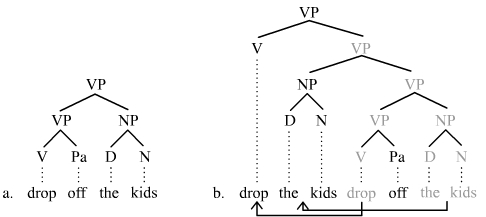

Syntactic movement is the means by which some theories of syntax address discontinuities. Movement was first postulated by structuralist linguists who expressed it in terms of discontinuous constituents or displacement. Certain constituents appear to have been displaced from the position where they receive important features of interpretation. The concept of movement is controversial; it is associated with so-called transformational or derivational theories of syntax. Representational theories, in contrast, reject the notion of movement, often addressing discontinuities in terms of feature passing or persistent structural identities instead.

In linguistics, inversion is any of several grammatical constructions where two expressions switch their canonical order of appearance, that is, they invert. There are several types of subject-verb inversion in English: locative inversion, directive inversion, copular inversion, and quotative inversion. The most frequent type of inversion in English is subject–auxiliary inversion in which an auxiliary verb changes places with its subject; it often occurs in questions, such as Are you coming?, with the subject you is switched with the auxiliary are. In many other languages, especially those with a freer word order than English, inversion can take place with a variety of verbs and with other syntactic categories as well.

Scrambling is a common term for pragmatic word order. In the Chomskyan tradition, every language is assumed to have a basic word order which is fundamental to its sentence structure, so languages which exhibit a wide variety of different orders are said to have "scrambled" them from their "normal" word order. The notion of scrambling has spread beyond the Chomskyan tradition and become a general concept that denotes many non-canonical word orders in numerous languages. Scrambling often results in a discontinuity; the scrambled expression appears at a distance from its head in such a manner that crossing lines are present in the syntactic tree. Scrambling discontinuities are distinct from topicalization, wh-fronting, and extraposition discontinuities. Scrambling does not occur in English, but it is frequent in languages with freer word order, such as German, Russian, Persian and Turkic languages.

In linguistics, negative inversion is one of many types of subject–auxiliary inversion in English. A negation or a word that implies negation or a phrase containing one of these words precedes the finite auxiliary verb necessitating that the subject and finite verb undergo inversion. Negative inversion is a phenomenon of English syntax. The V2 word order of other Germanic languages does not allow one to acknowledge negative inversion as a specific phenomenon, since their V2 principle, which is mostly absent from English, allows inversion to occur much more often than in English. While negative inversion is a common occurrence in English, a solid understanding of just what elicits the inversion has not yet been established. It is, namely, not entirely clear why certain fronted expressions containing a negation elicit negative inversion, but others do not.

In linguistics, a discontinuity occurs when a given word or phrase is separated from another word or phrase that it modifies in such a manner that a direct connection cannot be established between the two without incurring crossing lines in the tree structure. The terminology that is employed to denote discontinuities varies depending on the theory of syntax at hand. The terms discontinuous constituent, displacement, long distance dependency, unbounded dependency, and projectivity violation are largely synonymous with the term discontinuity. There are various types of discontinuities, the most prominent and widely studied of these being topicalization, wh-fronting, scrambling, and extraposition.

Extraposition is a mechanism of syntax that alters word order in such a manner that a relatively "heavy" constituent appears to the right of its canonical position. Extraposing a constituent results in a discontinuity and in this regard, it is unlike shifting, which does not generate a discontinuity. The extraposed constituent is separated from its governor by one or more words that dominate its governor. Two types of extraposition are acknowledged in theoretical syntax: standard cases where extraposition is optional and it-extraposition where extraposition is obligatory. Extraposition is motivated in part by a desire to reduce center embedding by increasing right-branching and thus easing processing, center-embedded structures being more difficult to process. Extraposition occurs frequently in English and related languages.

Subject–verb inversion in English is a type of inversion where the subject and verb switch their canonical order of appearance so that the subject follows the verb(s), e.g. A lamp stood beside the bed → Beside the bed stood a lamp. Subject–verb inversion is distinct from subject–auxiliary inversion because the verb involved is not an auxiliary verb.