The endomembrane system is composed of the different membranes (endomembranes) that are suspended in the cytoplasm within a eukaryotic cell. These membranes divide the cell into functional and structural compartments, or organelles. In eukaryotes the organelles of the endomembrane system include: the nuclear membrane, the endoplasmic reticulum, the Golgi apparatus, lysosomes, vesicles, endosomes, and plasma (cell) membrane among others. The system is defined more accurately as the set of membranes that forms a single functional and developmental unit, either being connected directly, or exchanging material through vesicle transport. Importantly, the endomembrane system does not include the membranes of plastids or mitochondria, but might have evolved partially from the actions of the latter.

Endocytosis is a cellular process in which substances are brought into the cell. The material to be internalized is surrounded by an area of cell membrane, which then buds off inside the cell to form a vesicle containing the ingested material. Endocytosis includes pinocytosis and phagocytosis. It is a form of active transport.

A lysosome is a membrane-bound organelle found in many animal cells. They are spherical vesicles that contain hydrolytic enzymes that digest many kinds of biomolecules. A lysosome has a specific composition, of both its membrane proteins and its lumenal proteins. The lumen's pH (~4.5–5.0) is optimal for the enzymes involved in hydrolysis, analogous to the activity of the stomach. Besides degradation of polymers, the lysosome is involved in cell processes of secretion, plasma membrane repair, apoptosis, cell signaling, and energy metabolism.

Exocytosis is a form of active transport and bulk transport in which a cell transports molecules out of the cell. As an active transport mechanism, exocytosis requires the use of energy to transport material. Exocytosis and its counterpart, endocytosis, are used by all cells because most chemical substances important to them are large polar molecules that cannot pass through the hydrophobic portion of the cell membrane by passive means. Exocytosis is the process by which a large amount of molecules are released; thus it is a form of bulk transport. Exocytosis occurs via secretory portals at the cell plasma membrane called porosomes. Porosomes are permanent cup-shaped lipoprotein structure at the cell plasma membrane, where secretory vesicles transiently dock and fuse to release intra-vesicular contents from the cell.

Endosomes are a collection of intracellular sorting organelles in eukaryotic cells. They are parts of endocytic membrane transport pathway originating from the trans Golgi network. Molecules or ligands internalized from the plasma membrane can follow this pathway all the way to lysosomes for degradation or can be recycled back to the cell membrane in the endocytic cycle. Molecules are also transported to endosomes from the trans Golgi network and either continue to lysosomes or recycle back to the Golgi apparatus.

In cellular biology, pinocytosis, otherwise known as fluid endocytosis and bulk-phase pinocytosis, is a mode of endocytosis in which small molecules dissolved in extracellular fluid are brought into the cell through an invagination of the cell membrane, resulting in their containment within a small vesicle inside the cell. These pinocytotic vesicles then typically fuse with early endosomes to hydrolyze the particles.

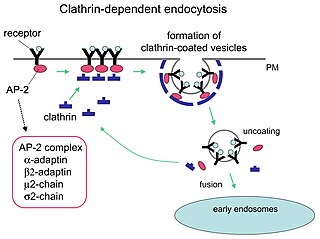

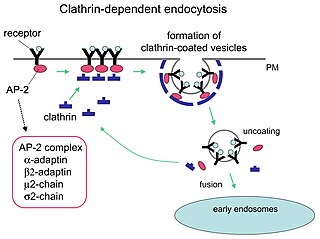

Receptor-mediated endocytosis (RME), also called clathrin-mediated endocytosis, is a process by which cells absorb metabolites, hormones, proteins – and in some cases viruses – by the inward budding of the plasma membrane (invagination). This process forms vesicles containing the absorbed substances and is strictly mediated by receptors on the surface of the cell. Only the receptor-specific substances can enter the cell through this process.

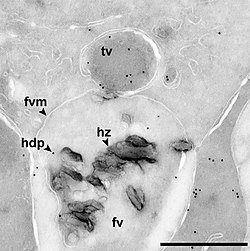

In cell biology, a phagosome is a vesicle formed around a particle engulfed by a phagocyte via phagocytosis. Professional phagocytes include macrophages, neutrophils, and dendritic cells (DCs).

SNARE proteins – "SNAPREceptors" – are a large protein family consisting of at least 24 members in yeasts, more than 60 members in mammalian cells, and some numbers in plants. The primary role of SNARE proteins is to mediate the fusion of vesicles with the target membrane; this notably mediates exocytosis, but can also mediate the fusion of vesicles with membrane-bound compartments. The best studied SNAREs are those that mediate the release of synaptic vesicles containing neurotransmitters in neurons. These neuronal SNAREs are the targets of the neurotoxins responsible for botulism and tetanus produced by certain bacteria.

Cell physiology is the biological study of the activities that take place in a cell to keep it alive. The term physiology refers to normal functions in a living organism. Animal cells, plant cells and microorganism cells show similarities in their functions even though they vary in structure.

A vesicular transport protein, or vesicular transporter, is a membrane protein that regulates or facilitates the movement of specific molecules across a vesicle's membrane. As a result, vesicular transporters govern the concentration of molecules within a vesicle.

Microvesicles are a type of extracellular vesicle (EV) that are released from the cell membrane. In multicellular organisms, microvesicles and other EVs are found both in tissues and in many types of body fluids. Delimited by a phospholipid bilayer, microvesicles can be as small as the smallest EVs or as large as 1000 nm. They are considered to be larger, on average, than intracellularly-generated EVs known as exosomes. Microvesicles play a role in intercellular communication and can transport molecules such as mRNA, miRNA, and proteins between cells.

Syntaxin-6 is a protein that in humans is encoded by the STX6 gene.

-Cytosis is a suffix that either refers to certain aspects of cells ie cellular process or phenomenon or sometimes refers to predominance of certain type of cells. It essentially means "of the cell". Sometimes it may be shortened to -osis and may be related to some of the processes ending with -esis or similar suffixes.

Autophagy-related protein 8 (Atg8) is a ubiquitin-like protein required for the formation of autophagosomal membranes. The transient conjugation of Atg8 to the autophagosomal membrane through a ubiquitin-like conjugation system is essential for autophagy in eukaryotes. Even though there are homologues in animals, this article mainly focuses on its role in lower eukaryotes such as Saccharomyces cerevisiae.

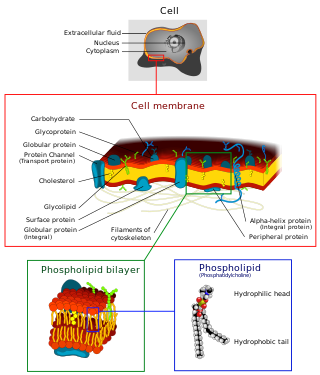

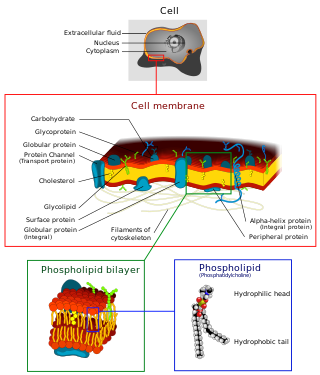

The cell membrane is a biological membrane that separates and protects the interior of a cell from the outside environment. The cell membrane consists of a lipid bilayer, made up of two layers of phospholipids with cholesterols interspersed between them, maintaining appropriate membrane fluidity at various temperatures. The membrane also contains membrane proteins, including integral proteins that span the membrane and serve as membrane transporters, and peripheral proteins that loosely attach to the outer (peripheral) side of the cell membrane, acting as enzymes to facilitate interaction with the cell's environment. Glycolipids embedded in the outer lipid layer serve a similar purpose. The cell membrane controls the movement of substances in and out of a cell, being selectively permeable to ions and organic molecules. In addition, cell membranes are involved in a variety of cellular processes such as cell adhesion, ion conductivity, and cell signalling and serve as the attachment surface for several extracellular structures, including the cell wall and the carbohydrate layer called the glycocalyx, as well as the intracellular network of protein fibers called the cytoskeleton. In the field of synthetic biology, cell membranes can be artificially reassembled.

Clathrin adaptor proteins, also known as adaptins, are vesicular transport adaptor proteins associated with clathrin. These proteins are synthesized in the ribosomes, processed in the endoplasmic reticulum and transported from the Golgi apparatus to the trans-Golgi network, and from there via small carrier vesicles to their final destination compartment. The association between adaptins and clathrin are important for vesicular cargo selection and transporting. Clathrin coats contain both clathrin and adaptor complexes that link clathrin to receptors in coated vesicles. Clathrin-associated protein complexes are believed to interact with the cytoplasmic tails of membrane proteins, leading to their selection and concentration. Therefore, adaptor proteins are responsible for the recruitment of cargo molecules into a growing clathrin-coated pits. The two major types of clathrin adaptor complexes are the heterotetrameric vesicular transport adaptor proteins (AP1-5), and the monomeric GGA adaptors. Adaptins are distantly related to the other main type of vesicular transport proteins, the coatomer subunits, sharing between 16% and 26% of their amino acid sequence.

Unconventional protein secretion represents a manner in which the proteins are delivered to the surface of plasma membrane or extracellular matrix independent of the endoplasmic reticulum or Golgi apparatus. This includes cytokines and mitogens with crucial function in complex processes such as inflammatory response or tumor-induced angiogenesis. Most of these proteins are involved in processes in higher eukaryotes, however an unconventional export mechanism was found in lower eukaryotes too. Even proteins folded in their correct conformation can pass plasma membrane this way, unlike proteins transported via ER/Golgi pathway. Two types of unconventional protein secretion are these: signal-peptid-containing proteins and cytoplasmatic and nuclear proteins that are missing an ER-signal peptide (1).

Membrane vesicle trafficking in eukaryotic animal cells involves movement of biochemical signal molecules from synthesis-and-packaging locations in the Golgi body to specific release locations on the inside of the plasma membrane of the secretory cell. It takes place in the form of Golgi membrane-bound micro-sized vesicles, termed membrane vesicles (MVs).

Intracellular transport is the movement of vesicles and substances within a cell. Intracellular transport is required for maintaining homeostasis within the cell by responding to physiological signals. Proteins synthesized in the cytosol are distributed to their respective organelles, according to their specific amino acid’s sorting sequence. Eukaryotic cells transport packets of components to particular intracellular locations by attaching them to molecular motors that haul them along microtubules and actin filaments. Since intracellular transport heavily relies on microtubules for movement, the components of the cytoskeleton play a vital role in trafficking vesicles between organelles and the plasma membrane by providing mechanical support. Through this pathway, it is possible to facilitate the movement of essential molecules such as membrane‐bounded vesicles and organelles, mRNA, and chromosomes.